Between January and February, Clubhouse, a platform for audio-only panel discussions, went from 2 million downloads to 10 million. By April it had garnered another 6 million downloads and a $4 billion valuation. The mobile app has been a go-to during the pandemic, for captive Americans stuck at home, and its popularity has sparked Twitter and Facebook to launch their own audio platforms. But it’s also allowed a bevy of smaller social audio apps to share the spotlight and push for an alternative form of social media, one that centers on authenticity.

CB Insights credits Clubhouse with birthing this new category, known as social audio, but the app hasn’t been the genre’s only success. As many people were trapped at home during the last year because of the pandemic, several platforms with audio and video at their center saw a spike. Spoon, a live audio platform that emerged in 2016, also rode the pandemic wave to 26 million downloads. In the wake of this social audio renaissance, Twitter, LinkedIn, Reddit, Facebook, and Spotify have either launched or promised to push live audio features of their own.

For those who haven’t deigned to check out Clubhouse and sit in on one of its many discussions, the mood is Ted Talk meets early online chatrooms. While it initially garnered a reputation for salon-style conversation among in-the-know venture capitalists and tech entrepreneurs, it has unsurprisingly morphed into something a bit more preachy. Now it’s all about experts on a stage imparting wisdom to the masses.

Clubhouse has been criticized for how it moderates its platform, both in terms of allowing discriminatory content and the way that it appends scarlet letter-esque visualizations to people who have been blocked. Still, despite a dip, Clubhouse continues to grow its user base. The company says it added 8 million users in the last five weeks. Other startups, like Peanut, which connects mothers and mothers-to-be, see Clubhouse’s rise as an opportunity to push new social platforms centered around intimate conversation.

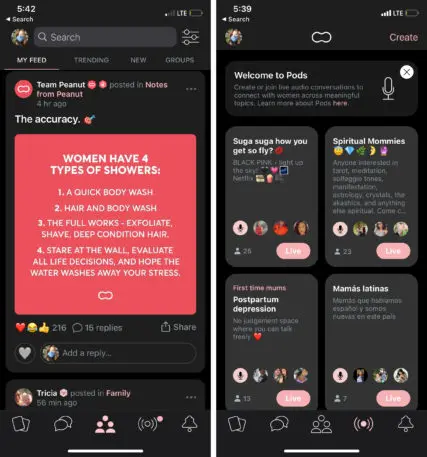

“There is no stage on Peanut, right? It’s not about that,” says Michelle Kennedy, the startup’s founder. Peanut originated as a sort of Tinder for moms: Swipe right on a mom you’d like to meet. The company has shifted since its initial launch in 2017 and now the app is much more about stoking conversations among everyone on the platform. In May, Peanut launched “pods” where women can meet to discuss or ask advice on certain topics, like how to navigate starting a family as a queer person or what it’s like to be on an antidepressant while also being pregnant. Everyone can participate in a conversation, though you have to request to speak so that people don’t talk over one another, says Kennedy. “It’s a participatory experience and in that way we’re democratizing the access,” she says.

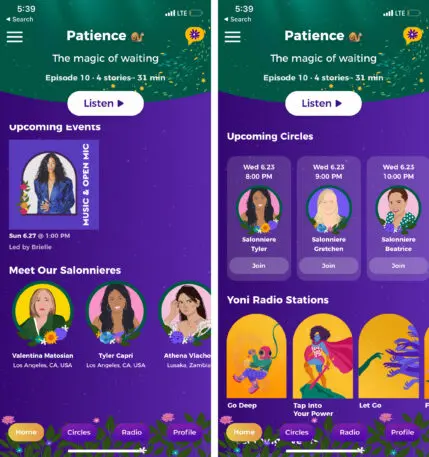

Two other apps, Quilt and Yoni Circle, are thinking similarly about using audio to foster community. Both are designed to give women more room to share stories in a safe space. At Yoni Circle, women can join hour long “circles,” small groups of of five or six, throughout the day to verbally share what’s on their mind and tell a related story about themselves. There is also Yoni radio, a 30-minute program featuring stories on a given topic, like patience, that allows women to listen and reflect without having to actively divulge.

Naj AustinWho is happy with the way that that system works? ”

“Who is happy with the way that that system works? Who is deriving joy from it and value?” asks Naj Austin, who has launched two social platforms that center people of color in the last year, both of which have audio as a core element. Austin, like many, is fed up with her experience on popular social networks like Twitter and Facebook, where abuse and misinformation run rampant. While these platforms have taken steps to mitigate both hate speech and dangerous disinformation campaigns, they’ve failed to stop it. That’s led Austin to work on entirely new ways of hosting social communities online.

Austin’s first platform, called Ethel’s Club, which pivoted from a physical coworking location, is a wellness-focused digital space for people of color. In the last year, it has offered group healing sessions during times of crisis, like after the death of George Floyd or the killing of several Asian massage parlor workers in Atlanta, and events like fireside chats and virtual dance parties. Her second is a social network called Somewhere Good. It’s designed to let people create “worlds” where they can share audio snippets, text, pictures, and links on a given subject. It’s an asynchronous experience and the audio operates as a voice note, a way to add some thoughts or a story without typing it out. Austin says people who post must also cite their sources. “We want it to become secondhand nature,” she says of the citations.

Building features like these from the ground up will also help with moderation efforts as they grow. “We’re trying to breathe life into the way that we share knowledge, make it a more real human-to-human [experience], versus it being this very flat, ‘I am the speaker. I control the stage. No one can combat me or tell me that I am making things up.'”

Audio is also how these platforms are trying to introduce authenticity to social media. It is a much different experience to hear someone say something or tell a story than it is to read a block of text and try and interpret the tone with which it’s being said. In this way, these new audio social platforms are rethinking what means to be social online.

“We actually don’t call people on our platform users,” says Austin. “We call them people because that’s what they are.”

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly represented the number of downloads Clubhouse received last month.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.