The geospatial fraud was as rampant as it was frivolous, but a bigger danger was lurking.

Bo Zhao, a geographer focused on geographic information systems (GIS), was working on his PhD at the Ohio State University in the early 2010s when he began noticing that people on Twitter were using geotags in their tweets to lie about their locations. Some, it seemed, were trying to fool people into thinking they were witness to global news events, but others appeared to be lying just for the ease of it.

Then in 2016, when the augmented reality smartphone game Pokémon Go became a global phenomenon, Zhao saw that people were using virtual private network (VPN) connections to fake their geolocation in the game in order to access the rare Pokémon targets pegged to real locations around the world. Essentially cheating, the trick also had an element of evening out the playing map. “The company actually distributes the Pokémon very unevenly. Some places have more, some places less,” says Zhao, now an assistant professor at the University of Washington’s department of geography. “This is actually a way to sidestep that imbalance.”

That led him to wonder what other more important geospatial data was being spoofed.

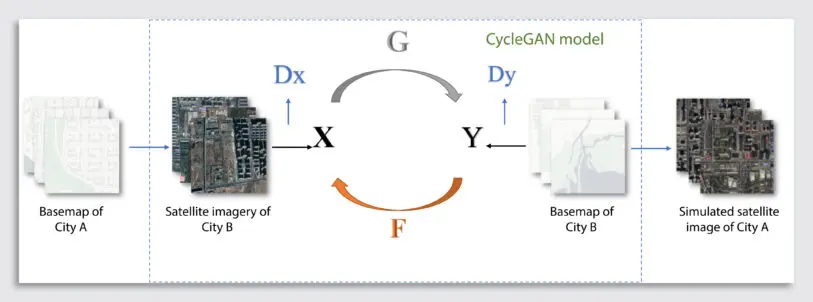

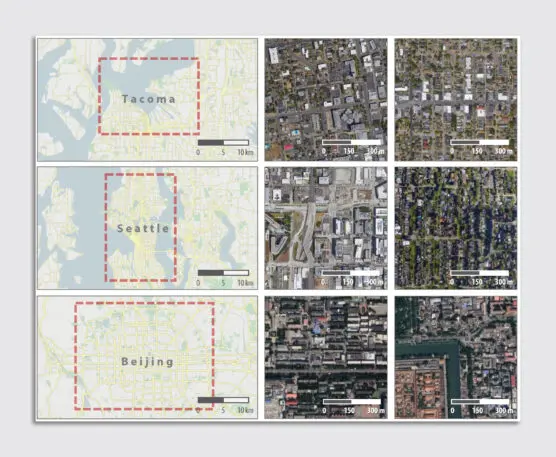

Zhao and colleagues from Oregon State University and Binghamton University began to look into satellite imagery, a major source of geospatial data used in applications ranging from climate observation to global shipping. In a recent paper, they explore the potential—and, as they show, the very real threat—of people using artificial intelligence to create convincing but fabricated satellite imagery. Like AI systems that have been created to generate realistic faces or malicious pornographers who’ve used cruder systems to make fake explicit videos using the likenesses of celebrities, Zhao and his colleagues have shown that deepfake satellite imagery can also be made.

Their paper, published recently in the journal Cartography and Geographic Information Science, used maps and satellite images from Seattle and Beijing to create real-looking but fake satellite images of a neighborhood within the city of Tacoma, Washington. In the images, Tacoma roads appear in their accurate locations, but buildings from either low-rise Seattle or high-rise Beijing have been swapped in. At face value, the images appear to represent real places.

But Zhao and his colleagues aren’t just opening a Pandora’s box of potential geospatial deepfakery. They’ve also begun to develop an approach to help identify when satellite images are actually AI creations. Zhao says it could take the form of an application programming interface that geographers can use in conjunction with geographic information systems like ArcGIS.

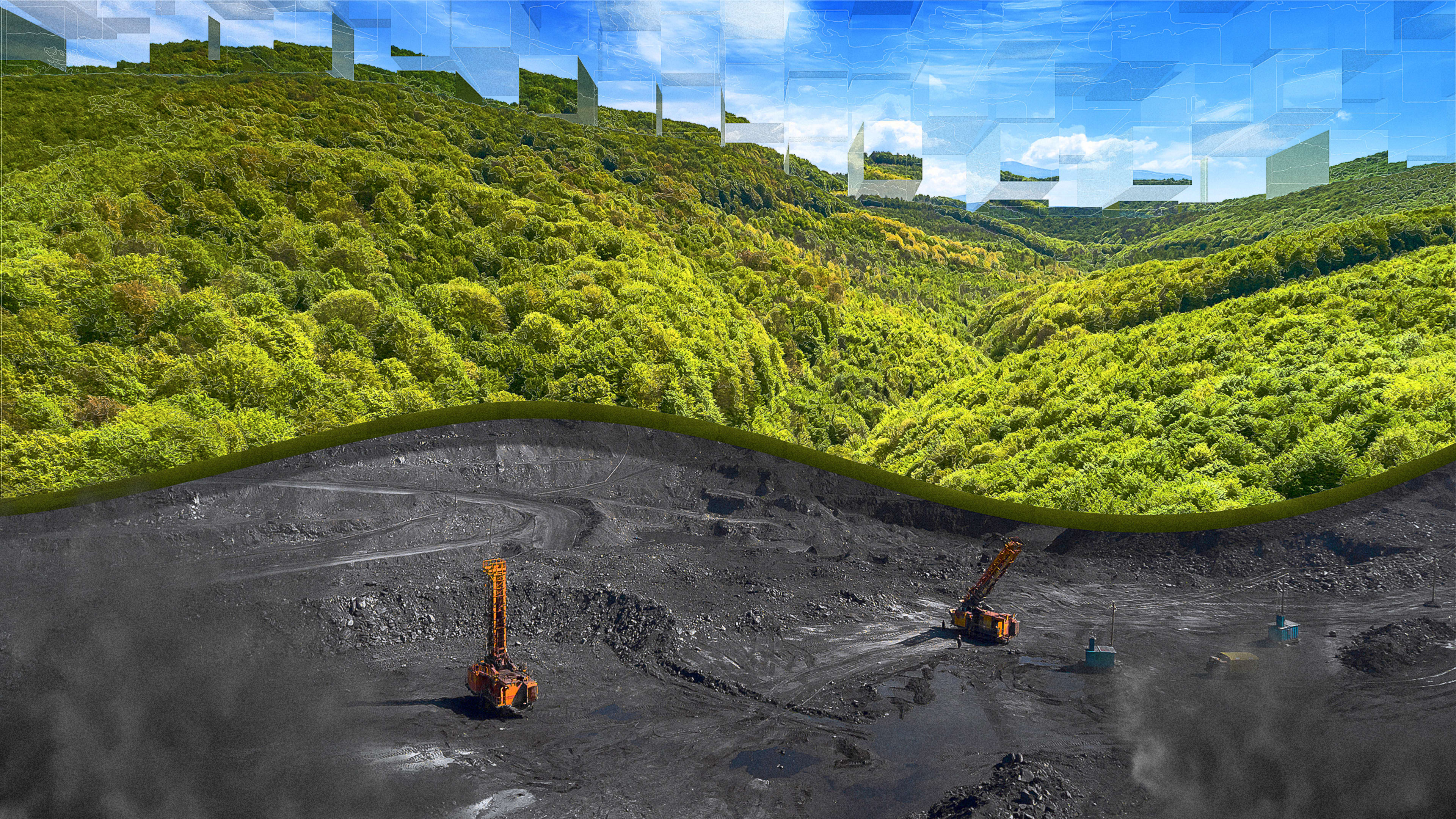

Faked satellite images aren’t necessarily problematic. The approach could also be used for good, Zhao says. For example, an AI-generated image could be used to estimate and fill in missing data from long-term climate change observations, helping to provide information that can inform future projections. In an urban development context, an AI-generated satellite image could envision how a city or region would change over time if development were left to sprawl uncontrolled.

Zhao says that whether they’re used for good, bad, or to cheat on Pokémon Go, faked geospatial data should be a wake-up call to anyone relying on this data. The push among some computer scientists to make artificial intelligence more accessible to the general public could lead to people faking map data as easily as they fake celebrity videos.

“There’s a saying in cartography: The map is not the territory,” Zhao says. “It’s mainly a subjective argument which was made by the mapmaker. So it really depends on who made it, and for what specific purpose. And as the bar for using AI becomes really low, it will be a challenge for us to know the real intention behind things.”

Zhao is calling on his colleagues in the computer science and geography worlds to be more cautious about the data they rely on, and to develop a set of ethics by which geospatial data is created and used. “I’m trying to encourage people not to use geospatial data without question or critique,” he says. “People need to realize that geospatial data could be misused or could be generated for malicious purposes.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.