Architect David Rockwell splits his time between two worlds.

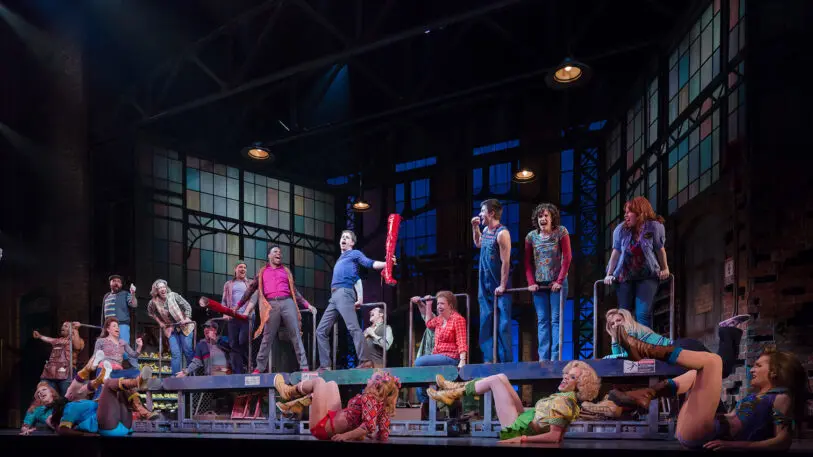

His architecture practice, Rockwell Group, is a 250-person powerhouse and designs high-end restaurants, hotels, and office interiors all over the world, from the Ritz-Carlton in Boston to the Omnia nightclub at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas. But he also puts his expertise to use on the stage, designing Broadway shows such as Kinky Boots and Hairspray, and even the miniature sets for the marionette film Team America: World Police.

In his new book Drama, out now from Phaidon, Rockwell explores the shared principles that guide these very different types of work. With collaborator Bruce Mau and editor Sam Lubell, Rockwell defines six categories that underpin the design approach he takes to projects, whether for an office building or a stage show: audience, ensemble, worlds, story, journey, and impermanence.

Here, Rockwell explains how these six concepts materialize in his work, and why he doesn’t really see a dividing line between architecture and theater.

Fast Company: You write in the book that an early interest in theater led you to become an architect. What was that path?

David Rockwell: My earliest interest in design was probably influenced by some genuine fascination with how environment affects connection. We moved from Chicago to the Jersey Shore when I was about 4. I was the youngest of five boys, and somehow my interests were around making things. I had a great laboratory—a second-floor space in a garage where I would collect things. I didn’t know who Rube Goldberg was yet, but I did know the game Mouse Trap, and I was constantly making low-tech installations and inviting people in. And then I got interested in theater because in that town my mother helped to found a community theater. Everyone in town was connected to that theater during the summer. They wanted to be in it, they wanted to help make it, they wanted to listen to it. It was a massive community-built community connection that I felt in a very profound way. In this little suburb, almost everything took place in private homes other than this community theater. So it was the other-than space that really attracted me, rather than homes, and that’s in some ways indicative of the kind of work I’ve pursued.

I went to architecture school, which really was just a good guess, because I don’t think there’s any way to really know. I went to Syracuse and then did some time at the Architectural Association of London, and I worked every summer in New York. The year I went to London, I came back and interned for a Broadway lighting designer named Roger Morgan. And that convinced me for a while that I didn’t want to work in theater, because while I loved him, it was a very contentious business. He was an amazing mentor, and I became more interested in applying theories and thoughts and impressions of theater to architecture. From a distance I got to see this mythic world of theater, and I didn’t see a way in that was permeable by me, so my decision was I would just be a fan of theater and move on as an architect.

You founded your firm in 1984, and started out primarily in hospitality projects, including the original Nobu sushi restaurant in the Tribeca neighborhood of Manhattan. But you did eventually end up getting into theater design, in a pretty big way, from Broadway to the Oscars ceremonies. How do your architecture projects and your theater projects overlap?

The reality is I never saw the boundary between theater and architecture. I felt there was this thrilling feedback loop. And as I began to do work in both, the work I would do in one field would in some ways affect the work my studio was doing in the other field.

As I began to take on theater projects, I tried to understand where my interest in theater and the needs of a director would overlap. The aha moment for me was that the single thing that most interested me in architecture was transitions, the way a place can transport you, the way a portal can frame something, the way the Spanish Steps [in Rome] are both a place to see a performance or be the performer. The notion of transition was what I found most directors were really most interested in. In theater that’s one tool in the toolbox you don’t get in architecture generally, and that’s things get to move.

[In architecture] I’m interested in the mechanics of how an audience moves through a space, and how they experience a story, and that’s very much like choreography in theater. We’re working on a project for Johns Hopkins that is a reworking of the Newseum building in Washington D.C., which is a seven-story building with a large atrium. The guiding design strategy is to push as much of the program to all the levels, so that it draws you up the building, and you’re moving toward something that’s an attractor.

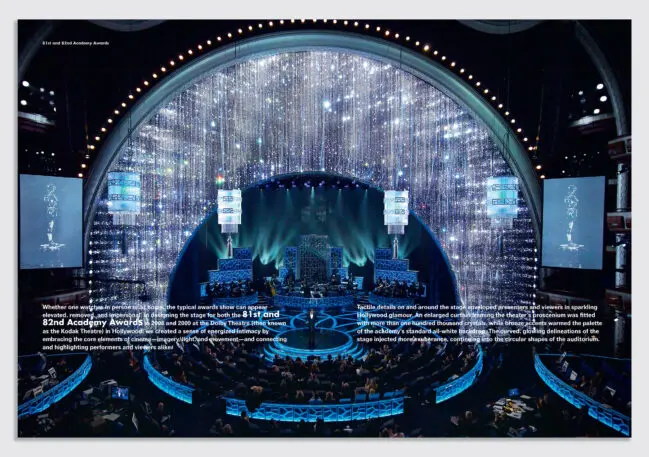

Another part of designing for an audience that we explore in the book is the notion of empathy. That there’s a way you’re welcomed and embraced by a space. The Oscars this year was an example of taking a train station [Los Angeles’s Union Station] and creating a place where those 170 people in the audience would feel welcomed and safe inside a much bigger building.

One of the chapters in the book is called “Story.” For your theater projects, the concept of story is pretty ingrained in the design. How is there story in a restaurant or an office?

I think what story does is it creates this anchor that gets everyone on the same page. I think the stronger element is the backstory. What is the why of the space. And none of that needs to be legible. As a designer, it gives you a narrative that allows you to make decisions that aren’t arbitrary, and I think that creates a space that’s cohesive.

One case where narrative and story drove the process is the Warner Music Group project, which is an old 1930s Ford factory building in downtown L.A. When we got involved we realized the building would have six or seven different music labels. They each have their own legacy and history, so we had to create a backstory that in some way made each of these labels individual but better together. We wanted to create a notion that being better together in the building was built into the DNA. So the backstory was they’re all about performance. We took the center lobby and layered the space with tiered conference rooms that are shared by the labels. And in the evening, the lobby becomes a performance venue.

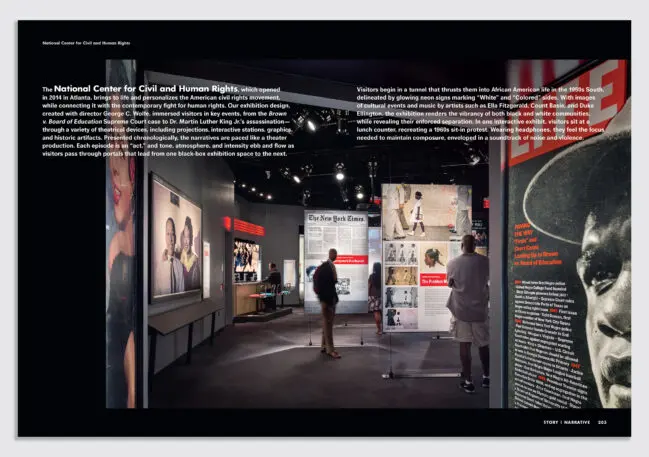

Another example would be the National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta. The narrative piece that drove the design was the fact that it was two different kinds of exhibition spaces, one very linear and narrative on the civil rights side, and the story on the human rights side is very much changeable and not fixed. The connection was the stairs where you move from one level to the other, and those stories feather into each other. So the narrative was the overlap between the two stories, and the ability of the linear civil rights story to interact with the ongoing human rights story.

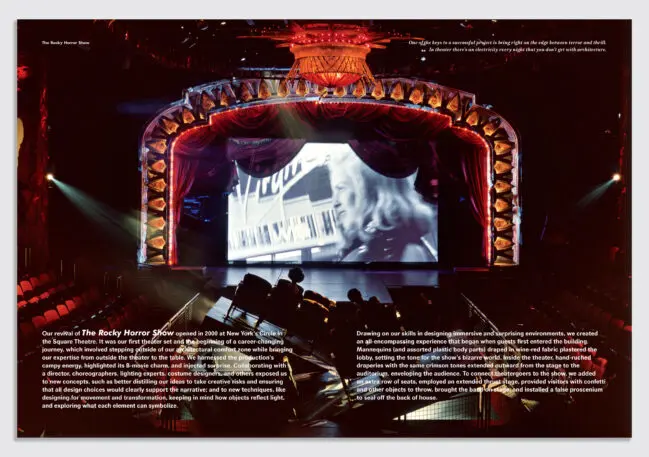

Your first Broadway design was for The Rocky Horror Show in 1999, and that led to a long string of other work in theater. Are there any ways you see that experience influencing your other designs?

The theater [for The Rocky Horror Show] had some intense limitations. It’s almost theater in the round, so you couldn’t do any kind of renaissance perspectival things because the audience was on top of you, 270 degrees. There was also no fly space for the scenery. We put a disproportionate amount of the effort into overcoming the limitations of the space by creating scenery that would unfold, that has to break apart and move horizontally. The floor actually flipped, so you could take that moment of going from the world of B movie theaters to the world of Rocky Horror in a way that was very memorable.

That would relate to something like Nobu Downtown, where the upstairs is a landmarked space in which we could attach nothing to the ceiling. It’s an incredibly beautiful interior, with these huge fluted columns. So again we found that limitation. Although there was a much less strict budget limitation, the design partly came from that limitation. We made all of the furniture freestanding including the bar, and built lighting into all the furniture so that even though it’s a huge, 24-foot-tall space, the glow at about 6 feet high comes from all the furniture lighting upwards.

One other point worth making given the point where we are with the pandemic is we look at impermanence in one of the chapters. Of course everyone wants to create permanent contributions, but ultimately mostly nothing is permanent. Things do change, and I think theater is such an inherently ephemeral medium that it does inspire architectural solutions. They aren’t right for every kind of architecture but they do inspire things that are adaptable, malleable, not impervious. I think one of the things that’s become really clear to me is how important adaptability is.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.