Elon Musk is notably absent for the soft opening of the Las Vegas Convention Center (LVCC) Loop , a system of two cramped tunnels, two surface turnarounds, and one underground terminal that the billionaire CEO of Tesla and SpaceX has advertised as the future of transportation. A handful of reporters have gathered for the media event in the Loop’s central station, an airy concrete bunker where 10 Tesla sedans, gleaming under a bank of pulsing LED lights, stand ready to ferry visitors across the convention complex.

This is the inaugural project of the Boring Company (TBC), the impishly named transportation startup Musk founded in 2016 after growing frustrated with Los Angeles’s famously gridlocked traffic. His original, grandiose vision had been to ease his commute by digging tunnels from Westwood, near his former home in Bel Air, to the Los Angeles International Airport, using electric skates to transport cars at up to 150 miles per hour. But the usual suspects—regulators, environmentalists, and residents—raised the usual objections, and the proposal stalled amid a flurry of legal challenges. Finally in 2019, after failing to court other major cities, Musk found a willing partner in his spiritual hometown: Las Vegas.

“We simplified this a lot,” Musk conceded in October. “It’s basically just Teslas in tunnels at this point, which is way more profound than it sounds.”

Hill, an Ohio transplant who moved to Vegas by pick-up truck in 1987, has become an integral part of Nevada’s economic overhaul. He helped lure Tesla to the state in 2014 as director of the Nevada Governor’s Office of Economic Development and was happy to continue the relationship with Musk in 2018 when he became president of the LVCVA. The tourist authority is now paying another $6.25 million for TBC to maintain and operate the Loop through next June. Beyond shuttling conventioneers, it will also act as a test case for the larger expansion. If the project proves a success, Hill hopes Musk will be able to complete the entire Vegas Loop, a city and county project not involving the LVCVA that connects the convention center with the casinos, downtown, airport, and stadium.

[Video: Las Vegas News Bureau/Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority]Hill wraps up his introductory remarks and invites the group to board the waiting cars, which are equipped with Autopilot technology and, if Musk’s promises pan out, might one day drive themselves. But for now, they’re helmed by human drivers. Save for the whir of the electric engine, it’s a silent and smooth, if slightly claustrophobic, jaunt, topping 40 miles per hour before slowing to climb a ramp to the West Hall surface station. The car circles back down to the underground station and up to the South Hall surface station before returning once again to the central hub.

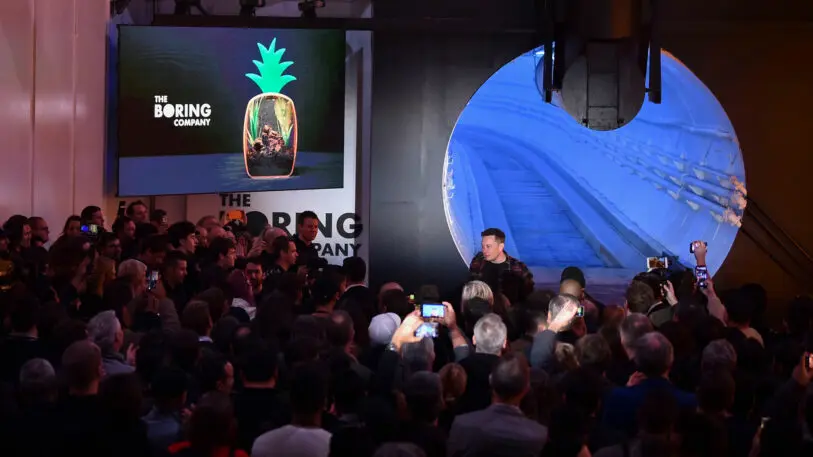

The fluid ride and sleek industrial design are a considerable step up from the bumpy makeshift prototype unveiled to reporters and investors in December 2018, at an over-the-top function at TBC’s headquarters in Hawthorne, CA. For that initial demonstration, Musk had arranged a grand spectacle, including a Monty Python and the Holy Grail-themed watchtower complete with a knight hurling insults in a bad French accent, a live snail posing as the company mascot, and guests firing TBC-branded flamethrowers into the air.

Yet as slick as the completed Vegas tunnel appears, it’s hard not to feel disappointed. Even if the LVCC Loop ultimately serves its purpose and transports the promised number of conventioneers, it’s under-delivered on a conceptual level: What began as an idea to revolutionize transportation has become little more than a $50 million advertisement for Tesla and, by extension, for Musk himself.

“One of Musk’s great brilliances is that he’s really good at the drama of unveiling an idea and making that idea seem earth-shattering and amazing,” says urban planner Christof Spieler, a VP at Huitt-Zollars and lecturer at Rice University in Houston. “He unveiled this technology that was supposed to be pods moving at incredibly high speeds in vacuum tunnels,” he continues. “If he had put out a video and said, ‘Imagine a future that’s a tunnel for taxi cabs,’ nobody would have gotten excited.”

“They’re calling it a people mover, which infers that the public is going to be moved around. But it was never designed for workers who don’t have a car and have to wait for a bus in 118-degree heat,” says Bob Fulkerson, cofounder of the Progressive Leadership Alliance of Nevada, a statewide economic watchdog coalition. “It was designed to help move tourists around. It’s just a nice little gizmo for the rich people.”

For a city of gamblers and glitz, conflating the needs of tourists and commuters may suit just fine. As Hill notes at the press event, the LVCC Loop has already exceeded his expectations in part because its central station also doubles as an entertainment venue. But what is at stake with the success of the Boring Company’s debut tunnel is far bigger than Las Vegas. Musk is certain to please his most unshakeable fans, for whom this latest showpiece will undoubtedly be taken as further evidence of his genius—even as his critics question whether the LVCC and Vegas loops ignore the diverse needs of real people. Are these Loops more Muskian sleight of hand? Or is this simply what happens when the ambition to fundamentally reimagine transportation runs into reality?

An eroding vision

Musk has a long history of hyperbolic goals—colonizing space, electrifying the auto industry, fully automating driving, and even creating a functioning brain–computer interface. But he is the rare entrepreneur for whom even downgraded versions of his original visions appear transformational, or at least prophetic.

That’s certainly the case with the Boring Company and the LVCC Loop, which evolved out of Musk’s 2012 conception of the Hyperloop. Adapting an idea first proposed by physicist Robert Goddard in 1904, Musk’s Hyperloop was to propel pods levitating on either magnetic fields or cushions of compressed air through tubes maintained in partial vacuum to reduce air resistance. The technology could theoretically enable speeds of 760 miles per hour, with more advanced versions approaching hypersonic velocities. He made his plans open-source to encourage others to develop their own proposals.

The company claimed to cut tunneling costs by 15 times to $10 million per mile by reducing the tunnel diameter, switching from diesel to electricity, and increasing boring speed with the use of more power, continuous drilling, and automation. Once operational, Musk asserted, Loops would be compatible with and pave the way for eventual Hyperloop networks. During 2018 and 2019, TBC raised $233 million through private investors and Musk’s own money, allotting some equity to early employees and to SpaceX, for an estimated $920 million valuation. It earned another $11 million through sales of company-branded hats and flamethrowers, the latter of which has since caused legal headaches for some of its owners.

Meanwhile, TBC’s highly touted plans for Loops in other cities began falling through. In 2017, Musk walked back his claims that he had received verbal approval to build a New York to Washington, D.C. Hyperloop tunnel after government officials denied it. In Los Angeles, a 2018 lawsuit by residents and community groups thwarted plans for a Loop adjacent to the 405 Freeway, while a 4-mile Dugout Loop connecting Dodger Stadium to a nearby L.A. Metro station fizzled. A potential Chicago Express Loop connecting Chicago O’Hare International Airport to downtown Chicago lost steam with the 2019 election of a new mayor who opposed the project. And a proposed 35-mile Washington D.C to Baltimore Loop also stalled. In April, those projects all disappeared from the TBC website.

But Hill and the LVCVA were undeterred. Musk, after all, had been good to the state of Nevada. A 2018 report found Tesla’s Gigafactory 1, occupying some 370 acres in Reno-adjacent Storey County, exceeded the initial forecasts for new jobs and local business support that it expected to bring in exchange for $1.3 billion in state tax subsidies. It also helped diversify the local leisure-based economy with more manufacturing jobs. Though local critics have blamed the Gigafactory 1 for exacerbating the area’s housing crunch, local officials remain pleased with the deal. “[Tesla is] a small part of an overall evolution of our economy, and they’ve been very positive in that regard because they help brand us as a place for advanced manufacturing and technology,” says Mike Kazmierski, president and CEO of the Economic Development Authority of Western Nevada.

Musk’s showmanship fits right into a place that embraces the daring of speculation. “Nevadans possess a gambling spirit and indomitable drive towards exploring new frontiers, technologies, and ideas. Sometimes that plays out in our policies as they impact our relationship to technology companies,” says Devon Reese, a Reno, Nevada councilperson at large and partner with the legal firm of Hutchison & Steffen. “There were lots of folks who were just betting on Elon Musk as this mercurial, unique human being who moved fast and played loose. We seem to be a place that attracts those people. If you look at our history, it’s always been a place of gold rush and opportunity.”

[Video: Las Vegas News Bureau/Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority]In early 2019, the Boring Company won the LVCC Loop contract with its promise to save tens of millions of dollars relative to more conventional proposals and its potential to expand to the rest of the city. “This technology has the ability to change transportation not only here at the convention center . . . and here in Las Vegas, but around the country and around the world,” Hill told Curbed when the tunnel broke ground in November 2019.

On social media, Musk critics derided the enterprise as a P.T. Barnum rebranding of something far more prosaic: a subway. “There isn’t a problem there that Elon Musk technology is actually addressing,” says Spieler. “We already know how to run a people mover between two buildings within a complex. What we’re seeing here is an attempt to take car thinking and apply it to public transit. And the capacity limitation of cars is inherent to cars.”

Christof SpielerThere isn’t a problem there that Elon Musk technology is actually addressing.”

Public skepticism grew after an October 2020 report by TechCrunch estimated that the Loop specs, when conforming to fire codes, might only move a quarter of the contracted 4,400 passengers per hour. That prompted a flurry of media and social media debate—from Australian tunnel enthusiast Phil Harrison backing Musk’s claims with computerized simulations to a vitriolic teardown on YouTube by British chemist Phil Mason. At rush hour, says Mason in the video, “all you’re going to do is replace sitting in a traffic jam with sitting in a queue to use an elevator.”

It’s hardly an idle concern. Standing in the central terminal, listening to Hill speak, it’s difficult to envision how efficiently throngs of attendees will move down the station’s single-file escalator, board the see-through elevator, or queue for the cars without creating bottlenecks. When asked, Hill’s representatives explain that passenger flow is still being tweaked.

Even amid rising criticism, Hill keeps doubling down on the same message he’s had for years: The project is “really innovative,” he insists during his press talk. His representatives later state via email that he’s referring to the fact that the project is the first underground transportation system for a convention center.

But even without being pressed, Hill admits that the underlying tunnel tech isn’t as revolutionary as Musk has claimed.

“The technology associated with it is not, frankly, a game changer; it’s a tunnel,” he says to the group. “We’ve been building tunnels for a long time. Those things are not technically difficult.”

The paradox of Musk

Musk’s ability to sell municipal officials like Hill on the Boring Company is part of a long pattern of brilliant marketing—or strategic misdirection, depending on who you ask. For nearly two decades, Musk’s whimsical marketing stunts and exaggerated claims have helped his personal brand become synonymous with the future, utopian or otherwise. He has expertly wielded the resulting hype to lure billions of investment dollars, government subsidies, and tax breaks.

That business savvy, combined with an unrelenting work ethic, have unlocked spectacular achievements. SpaceX, now valued at $74 billion, not only lowered launch costs, but returned crewed launches to American soil. Tesla reignited interest in electric vehicles by producing the world’s leading EV model, becoming the most valuable auto company in the world.

Of course, Musk is equally well known for the promises that haven’t panned out, from missed deadlines to wholesale fabrications. Musk has teased Tesla investors for years about the imminence of a “million-mile battery” and “full self-driving,” an autonomous driving feature that is always just a few months away. Drivers have been misled by the technology’s capabilities as well, reportedly leading to a series of crashes, some fatal. In 2018, Musk was sued by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) for falsely tweeting that he had secured funding for a private takeover of Tesla; as part of the resulting settlement, which the SEC maintains he continues to violate, he stepped down as chairman and agreed to certain limits on his tweets.

There is some method to the madness, given that speculative ventures often require more aspirational rhetoric to raise capital and galvanize employees. “The more novel, radical, or risky the idea, the bigger the challenge in acquiring the necessary resources,” Jeff Dyer, a professor of business strategy at Brigham Young University (BYU) in Provo, Utah, wrote in MIT Sloan Management Review. “Although many people say they like radical ideas, the greater the risk and uncertainty, the more skittish would-be supporters become. Innovators who learn how to win support are the ones who gain traction.”

Bruce ClarkHis goofy side—getting stoned in public, shooting a convertible into space—appeals to the inner 13-year-old in a lot of us.”

Musk’s unorthodox methods also draw constant press and awareness about his companies and products. “Musk’s high-profile social media and other activity, for better or worse, keep him and his company in the public eye,” says Bruce Clark, an associate professor of marketing at Northeastern University in Boston. “That he is also a tech visionary appeals to a lot of people who are glad to see someone try to do big, audacious things for (his view of) the betterment of humankind. And his goofy side—getting stoned in public, shooting a convertible into space—appeals to the inner 13-year-old in a lot of us.”

The downside to Musk’s childlike wonder, of course, is an equally juvenile disposition toward shareholders, regulators, employees, and customers—sometimes with grave consequences. Investors sued Tesla and Musk for misleading them into approving a $2.6 billion SolarCity purchase in 2016 despite the solar panel manufacturer’s insolvency. Last year, the Tesla board settled for $60 million, leaving Musk as the sole defendant. Meanwhile, the SolarCity Gigafactory 2 in Buffalo, NY remains far shy of the 5,000 jobs promised to secure a $750 million state investment. More recently, SolarCity came under fire for extreme price hikes of its solar roofs. In 2019, the National Transportation Safety Board found underperformance and overreliance on Tesla’s driver-assistance products contributed to fatalities alongside lax federal oversight. In April, two men died in a Texas crash of a Tesla that authorities say no one was driving, which Tesla disputes. In May, an Autopilot-activated Tesla killed its driver and injured two others after crashing into an overturned truck in California.

Another concern is whether Musk’s erratic behavior will impact TBC, given his increasing use of Twitter to attack critics and whistleblowers or flout the law. He kept his Fremont, California factory running in the spring of 2020, despite a state-mandated pandemic lockdown, which may have triggered a COVID-19 spike among its employees. Investigations by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), the Center for Investigative Reporting, and USA Today unearthed underreported work-related injuries at the Fremont site and Nevada Gigafactory. Last year, Tesla barred Nevada OSHA inspectors when they arrived at the Gigafactory with a sheriff’s deputy and warrant. Then there are the defamation lawsuits, most notably from British diver Vernon Unsworth in 2018 after Musk called him “pedo guy” on Twitter and “child rapist” to a reporter. Musk won that suit, but still faces others from Tesla critic and short seller Randeep Hothi and Tesla whistleblower Cristina Balanhow.

“His track record is quite astounding as far as what he’s accomplished, but there is a dark side,” says Brad Owens, an associate professor of business ethics at BYU. “If you have very aggressive Mount Everest goals that you’re doggedly committing to reach, the temptation to cut corners, to discard important considerations, or compromise moral commitments as you’re climbing the steep mountain, becomes greater.”

Brad OwensHis track record is quite astounding as far as what he’s accomplished, but there is a dark side.”

While Musk’s conduct makes him ever more polarizing, it also motivates his supporters, who see his legal scrapes as speeding tickets in the race for a better, greener, more civilized world. If Musk’s ultimate goal is, as he has said, to use his wealth to make humans a “multi-planet species,” then each new business venture is infused with world-historical purpose.

It’s not just Musk’s superfans who’ve bought this narrative. Plenty of investors have, too. “It’s hard to argue with Musk’s massive historic success on SpaceX, as well as Tesla,” says Daniel Ives, the managing director of Equity Research for Wedbush Securities. “We believe the Boring Company will follow that, even though it faces similar challenges as SpaceX and Tesla, such as massive R&D challenges, skeptics across the board, and trying to have a technological breakthrough with time ticking. I would be shocked if the Boring Company is not a massive success story over the coming years.”

But Musk’s hype strategy could implode if he can’t meet more demanding consumer and investor expectations. Depending on which analyst you speak to, Musk is either on the cusp of yet another stratospheric success, or everything is about to collapse.

“Elon appears to be a master of distraction. By the time anyone starts asking tough questions about one business, he’s moved onto another,” says David Trainer, CEO of New Constructs, an investment research firm. “Let’s face it, Musk is stretched pretty thin. We think the house of cards is starting to really implode here, because of everything he’s promised and invested in.”

The Vegas Loop

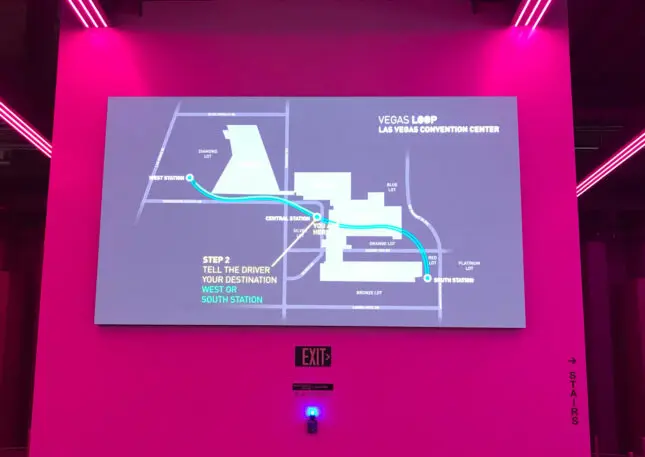

Long before the LVCC Loop was finished, Las Vegas and the surrounding Clark County began moving forward with the TBC’s proposal for a 15-mile citywide Vegas Loop, an underground tunnel system connecting the LVCC with the Vegas Strip, Downtown Las Vegas, McCarran International Airport, and Allegiant Stadium. Cars would run express trips to final destinations along the Loop without intermediate stops as on a subway.

But instead of Las Vegas footing the bill, TBC is assuming the role of developer, proposing the project as a private concern that pays the city a franchise fee to use its right of way. (That fee is still being negotiated, but would likely be 1% to 2% of gross revenues.) TBC would fund a central artery tunnel—two single-lane tunnels carrying a finite number of authorized Teslas in opposite directions and charge property owners, such as casinos, to construct their own stations with access ways to and from the main artery. Either franchise fees or private developers will fund stations in the Arts and Medical districts.

[Video: Las Vegas News Bureau/Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority]“Pre-COVID, Las Vegas was heading toward its highest levels of tourist visitation and we were seeing a need to improve our transportation system any way we could,” says Mike Janssen, executive director of the Public Works, Operations, and Maintenance for Las Vegas. “So when the Boring Company tunnel was proposed, it really just fell into that bucket of transportation modes that will help us meet the needs for our community. And when someone’s proposing to do it at no cost to the public, that’s just icing on the cake.”

When asked whether city officials had any concern with Musk’s overzealous timelines, erratic behavior, or the possibility that TBC could go bankrupt, Janssen cited Nevada’s success with the Gigafactory as precedent, adding that approval would come down to the final design, which is still pending. As with any developer, TBC would need to post bonds and insurance to cover project liabilities, abandonment, and decommissioning, he says. “It all comes back to managing the risks.”

But transportation experts believe even risk mitigation won’t compensate for what they say are the system’s fundamental design flaws, which mostly have to do with inefficiency and safety. They maintain that if TBC wanted to move as many people as subways, the number of tunnels, plus the requisite stations and safety measures, would approximate the cost of a conventional subway line.

“Oftentimes, when I see new technologies held up as cheaper, it’s because the people designing them are not following the safety standards that everybody else is following, which is not because of technology,” says Spieler. “If you took conventional technology and designed it to that same lower level of safety, you’d also get a lower cost.”

According to the National Association of City Transportation Officials, a single car lane like what the two Vegas Loops provide might move 600 to 1,600 people per hour (assuming one to two passengers per vehicle and 600 to 800 vehicles per hour), compared to a bus lane’s 8,000, and a rail lane’s 25,000 per hour per direction. Moreover, subway lines can move close to 100,000 people per hour.

“Those are some high projections,” says Janssen, who speculates they might reflect the maximum capacity of the entire tunnel system if all the cars were self-driving and there were five people per car. But what happens when human variance replaces uniform data points? “Passengers who may be slower to get in and out of the car during load/unload will absolutely affect total system capacity,” he says.

How fast Loop autonomy arrives is also up for debate, despite handfuls of driverless vehicles from other companies already operating within specific geographic domains. Although a tunnel is the simplest type of domain, station navigation is much trickier, says Edward Niedermeyer, communications director for Partners for Automated Vehicle Education. “It’s the people during loading and unloading, the cars pulling in and out, and the edge case of drunk people walking into the tunnels that [makes it] really complicated.”

A narrow tunnel diameter also brings up safety concerns. “If you look at the London Underground, for example, their oldest subsurface tunnels are very small; a lot are just under 12 feet,” Spieler adds, leaving insufficient evacuation space. “Over the last couple of decades, the transit world has concluded that’s not safe, that a tunnel requires an emergency evacuation walkway, with headroom to stand in, so that everybody can go out the side doors of the cars and get out of the tunnel.”

The TBC’s now-defunct 2019 D.C.–Baltimore Loop proposal had an insufficient number of emergency evacuation points and sub-par solutions like exit ladders, according to TechCrunch reporting. Spieler says this could partially explain TBC’s lower purported tunneling cost.

Another consideration are fires from EV high-voltage lithium-ion batteries, which can erupt spontaneously, produce more intense flames than gasoline, require more water and time to extinguish, and can reignite hours later. The aforementioned fiery Texas crash that burned passengers alive when their Model S electric door handles failed, took four hours and 30,000 gallons of water to douse, with authorities trying to contact Tesla for advice on putting out the fire.

Glenn CorbettThis is still a wilderness territory in terms of how these tunnels should be designed.”

According to Glenn Corbett, a professor of security, fire, and emergency management at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York, there hasn’t been enough testing done on how to suppress a battery fire in a tunnel. “This is still a wilderness territory in terms of how these tunnels should be designed,” he says. “In this case, the vehicle and perhaps the tunnel technology are outpacing the research.”

Hill maintains that the LVCC Loop is wide enough for passengers who would be, at most, within 1,200 feet of an exit, to open car doors and evacuate, even in wheelchairs. And if a car stops working, “the Boring Company has cars that can either pull or push the vehicles out to the nearest station,” he says, adding that first responders weighed in on safety features that include fire suppression systems embedded in the floor and four different communication systems. Clark County Fire Department deputy fire chief Warren Whitney offered a more brusque approach to a tunnel fire emergency in a recent interview with TechCrunch: “Our plan right now would be just to get the people out, then pull back and let the fire continue to burn.”

The Vegas anomaly

The gray area in tunnel safety is a symptom of a bigger problem: Cities are so strapped for cash that they increasingly look to private developers to build even basic infrastructure. Public–private partnerships can be more efficient, but they also represent a systemic failing: that government alone doesn’t have the ability to provide services for citizens and instead must outsource the work to developers, which have profit rather than the public good as priority number one.

These forces could put a cap on the possibilities for the Vegas Loop’s future. While the system is proposed as a private development with mostly casino-funded stations, it’s uncertain who would subsidize a theoretical expanded network into more residential areas that are far away from tourist meccas. The same goes for the two- to four-mile tunnel considerations in other cities. Miami mayor Francis Suarez floated the idea of seeking federal funds, which might be feasible, considering President Joe Biden’s proposed initiative to pour $621 billion into shoring up transportation infrastructure. But should tax dollars fund transit ventures that, as urban planners argue, don’t favor the masses?

[Video: Las Vegas News Bureau/Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority]The proposed Loop’s sample fares indicate distance-based rather than single-ride rates, ranging from $5 to $10—not quite the $1 rides Musk touted for a Los Angeles tunnel in 2018. While less than Uber and Lyft, it’s still higher per mile than Las Vegas buses, which charge $2 for single rides, and other subway systems, such as New York, which charges $2.75 for a single ride. In a daily commute, those numbers add up.

If the Vegas Loop does work out, the city still presents an unusual case study. “Even if it were to make money in Las Vegas, that wouldn’t actually be a sign that it would work elsewhere,” cautions Spieler. “One place where we know transit can make money is at tourist destinations, because what tourists will pay to take a bus or a train while they are on vacation far exceeds what people are willing to pay when [commuting to] their everyday work.”

A system that, however voluntarily, separates commuters from tourists counters the tenets of mass transit. “So what you’re achieving here is class segregation,” says public transit planning consultant Jarrett Walker, whose Portland firm conducted a transportation analysis of the Las Vegas Strip in 2014. “Even a privatized version is still a public investment if it occupies a public right of way. It’s going to take space, and it’s going to prevent other things you might do later on, like build a proper subway line.”

For the immediate future, the convention center’s tunnel at least seems poised as a post-pandemic attraction as the Vegas Loop gears up for an estimated ribbon cutting next year. The first true test of the LVCC Loop is this week’s convention crowd, where as many as 60,000 people are coming together for the World of Concrete. Yet already, Hill is tempering expectations for more highly trafficked conventions, like the Consumer Electronics Show, whose 150,000 visitors were initially slated to christen the Loop. “It’s not really intended to be the only transportation solution for really big shows,” says Hill. That might have always been the plan, but the message has been lost amid the controversy.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.