Right as the pandemic was getting underway in New York in April 2020, Joanne Schneider DeMeireles had a miscarriage. She knew something was wrong when she went in for a prenatal appointment and her obstetrician told her that her embryo was only five weeks along. “I was like, that’s not possible,” she says.

Her doctor dismissed her concern and told her to come back the following week for another ultrasound. Schneider DeMeireles had previously worked at a fertility clinic and knew when she ovulated, and she had been tracking her pregnancy obsessively. The small size of her embryo—how doctors track the age of the fetus—meant there might be a problem. The following week when she returned to the doctor, there was no heartbeat. It was a miscarriage, one that hadn’t yet expelled.

Schneider DeMeireles’s experience is not unique. But now she is one of many women inspired by their experiences with pregnancy, pregnancy loss, and postpartum care who are trying to change how women receive care. After her miscarriage, Schneider DeMeireles joined a new maternal health clinic called Oula as its chief experience officer. Oula is one of a bevy of startups focused on improving pregnancy care that includes clinics; apps that answer questions that doctors may not make time for; pregnancy trackers; and products like underwear with built-in slots for ice packs.

“Since we don’t have true data portability, you end up telling the same stories and you don’t have coordinated care across services,” says Leslie Schrock, an angel investor and author of the pregnancy guide Bumpin’: The Modern Guide to Pregnancy: Navigating the Wild, Weird, and Wonderful Journey From Conception Through Birth and Beyond.

The market for maternity care products is expected to surpass $3 billion by 2023, according to a 2018 report from Research and Markets. The cost of birth itself is high: an average of $14,000 nationally. Already some companies are seeing success in this space. Maven Clinic, an employee benefit that coordinates fertility, prenatal, and postpartum services for women, has raised nearly $100 million in funding, according to Pitchbook data, and secured clients like L’Oréal, BuzzFeed, and Snap. It stands to reason that pregnant people may be inclined to seek out doctors and services who can offer more for their money.

Reimagining in-person care

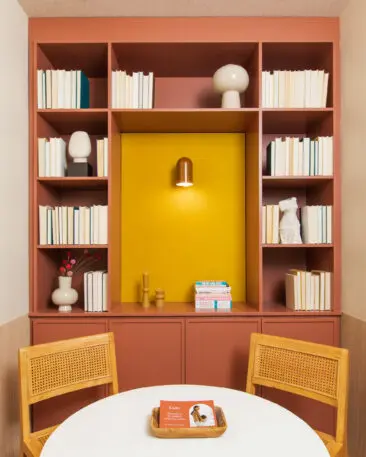

Oula is nestled between brownstones on a quaint block in Brooklyn, with a Kiehl’s just down the street. The entryway has a homier aesthetic than your average doctor’s office, but follows the same spatial rule book as design-forward practices like One Medical or the dental office Tend. The color palate is womb-like, with muted brown, pinks, and red. There is feminine art on the walls and the decor is round; even the floor tiles are adorned with ruddy little half moons. Just beyond its couches are toys for kids, and in the bathroom is a self-cleaning changing table from a Chicago based startup called Pluie.

The first appointment at Oula is one hour and can be either in person or online, though the clinic encourages people to do their first visit virtually. “A lot of clinics will not even speak to you until basically they can see something on an ultrasound, so we knew that that was something we wanted to do differently,” Schneider DeMeireles says. “We’ll talk to you as soon as you want us to—before you’re pregnant, if you want to just talk about even how to get pregnant. But what you need to know is that if you’re looking for an ultrasound, that won’t be possible until at least 7 weeks, and if you’re looking for genetic screening, that won’t be possible until at least 10 weeks.”

Midwives are also much less expensive to employ, allowing Oula to take insurance, including Medicaid, like any other clinic, but offer more appointment time. The company also has a digital platform where patients can hit up their caregivers for advice at home. Oula recently added the ability to message a midwife and build a care plan highlighting key decisions that need to be made during the pregnancy journey. The platform also provides guidance on when to plot out appointments between conception and birth, and an automated check-in that asks patients to report how they’re feeling. The site’s content can help answer basic questions pregnant people might have.

So far, Oula has just one clinic in Brooklyn and will deliver babies at Mount Sinai West. Eventually, it hopes to open its own birth center. In the meantime, it’s exploring the various aspects of how it wants to do care differently.

“We had our first missed miscarriage patient and [our team] came together and said, ‘Okay, we’re going to get them a little care package,'” says Elaine Purcell, Oula cofounder and COO. “Because again, this isn’t just [about medical protocol]. Let’s get them a journal, let’s start thinking about different ways for them to cope.”

New layers of support

In April, medical journal The Lancet published three papers on miscarriage and called for a complete rethink of miscarriage care. This year, a group of midwives launched a miscarriage kit called the Box for Loss. For $150, it includes Nyssa Care postpartum underwear, which has a pocket for an ice or heat pack, essential oils, a vaginal steam, CBD oil, crystals, and meditations.

Simmone Taitt, founder and CEO of Poppy Seed Health, says when her pregnancy ended in miscarriage her obstetrician offered no support. “She told me that my body had terminated the pregnancy. . . . She said, ‘But it’s fine, you can start trying again in a few months and I’ll see you when you’re back.’ And she walked out of the room,” Taitt says. “It was a few minutes. It was devastating. It was isolating.”

Simmone Taitt, Poppy Seed HealthIt was a few minutes. It was devastating. It was isolating.”

She started Poppy Seed Health, a mobile app with on-demand access to midwives, doulas, and nurses who can help people navigate their pregnancy and losses. The app is $29 per month, but for people who have just experienced a loss it’s free. “You give us your name and your pronoun, and you are—in under a minute—connected with someone on Poppy Seed Health who specifically is trained in holding a space for pregnancy loss, grief, and infant loss,” Taitt says, adding that scholarships are available to those on Medicaid so they, too, can access her platform.

Mental healthcare for pregnant people is sorely lacking. A 2018 report from nonprofit California Health Care Foundation says “perinatal mood and anxiety disorders are the most common medical complications affecting women during pregnancy and after childbirth.” In collaboration with the National Partnership for Women and Families, CHCF ran a survey that found 20% of pregnant women in California screened positive for anxiety. Another 11% screened positive for depression, more than the percentage of women who screened positive for postpartum depression. Pregnant Black women scored 10 percentage points higher for both anxiety and depression. Across race, only 20% of women experiencing mental health issues were able to get help.

Black women are also three times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This disparity creates yet another reason why women want to reinvent pregnancy care.

“Being a Black woman with great insurance, great education . . . and I still was not getting the medical attention . . . I needed because of my race,” Taitt says. “We’re not reimagining—we’re building something new.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.