Deep at the bottom of the ocean, there are vast fields of metal that could be critical for the future of renewable energy. The polymetallic nodules, which resemble potato-like clumps, are rich in nickel, cobalt, copper, and manganese—several of the key ingredients in lithium ion batteries, which are used in electric vehicles and solar energy storage systems. They’ve been known since the 1970s to exist in some of the darkest depths of the ocean. A new venture is hoping to bring them to the surface.

The Metals Company, a Vancouver-based metals and deep-sea mining company, is working on a project that will collect these nodules from a location 2.5 miles deep in a part of the Pacific Ocean known as the Clarion Clipperton Zone. The metal nodules will be brought up and shipped to an onshore processing facility, where they will be separated out for use in the production of batteries and other metal products, primarily in the form of nickel, which is the primary component of lithium ion batteries. The company has hired the global architecture firm Bjarke Ingels Group to design the robotic vehicles and vessels they’ll use to scoop up and transport these metal nodules, as well as the processing plant.

Despite the name, clean energy vehicles take a toll on the environment, mostly because of the metals their batteries require. For example, lithium, a key component of batteries for electronics and vehicles, is mined at a scale of tens of thousands of tons every year. Most metal comes from deep inside the earth, which results in a shocking amount of waste and environmental destruction from the mining and smelting required to prepare it for use in batteries. Mineral demand for clean energy technologies is expected to quadruple by 2040, according to a recent report from the International Energy Agency. The Metals Company’s proposition is that mining the deep sea for these resources is a less destructive alternative, though some environmental groups have taken issue with deep-sea mining.

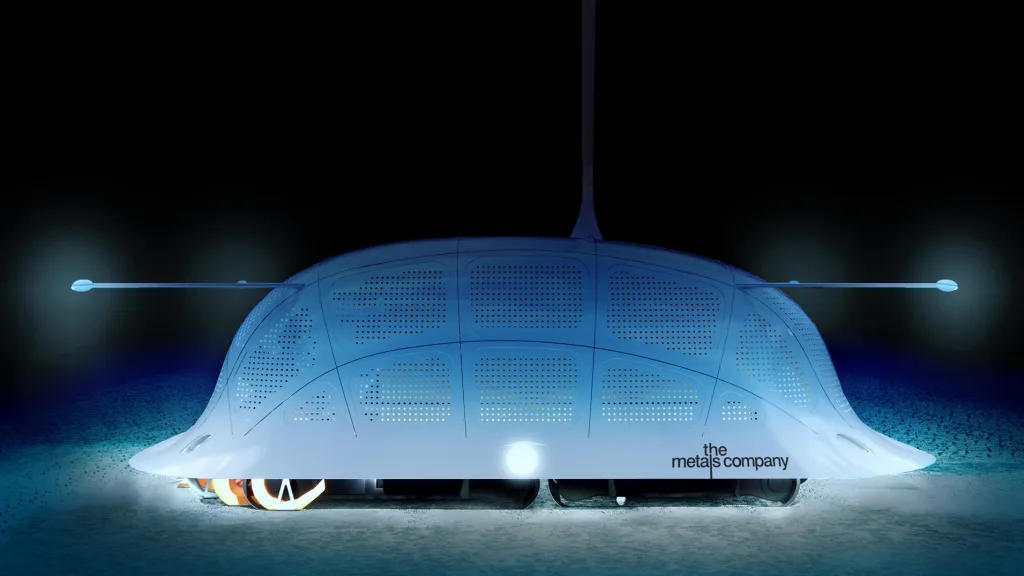

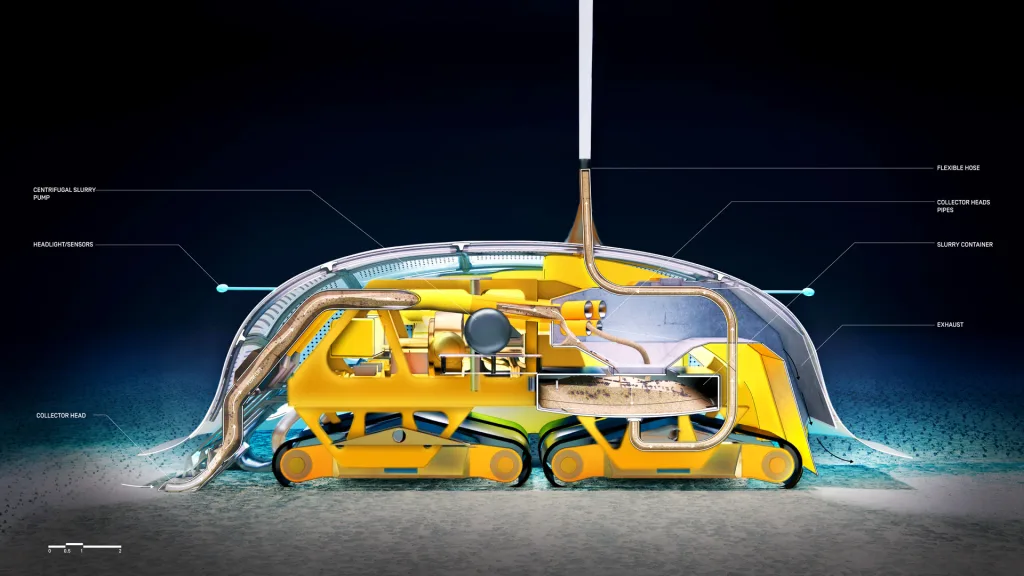

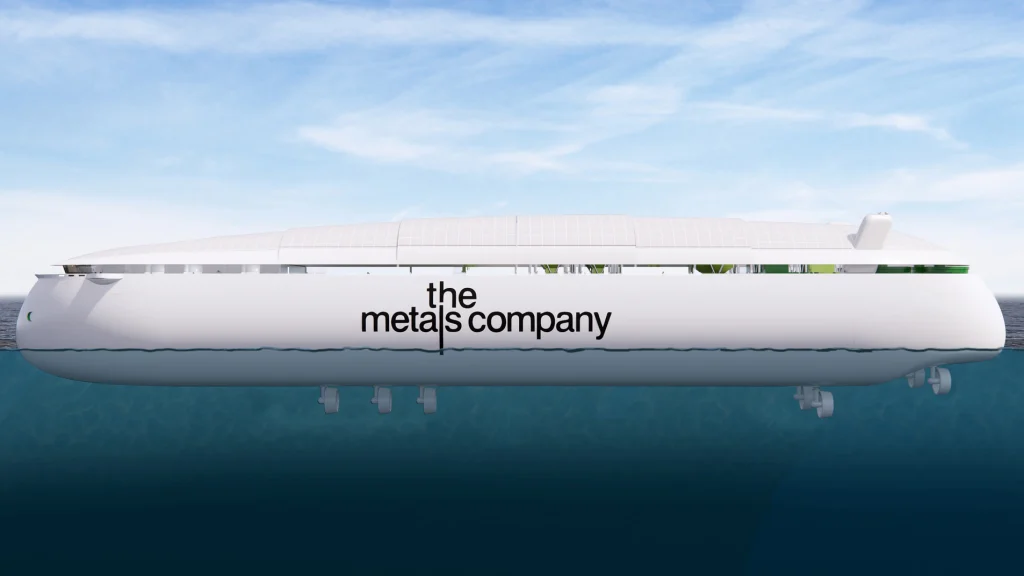

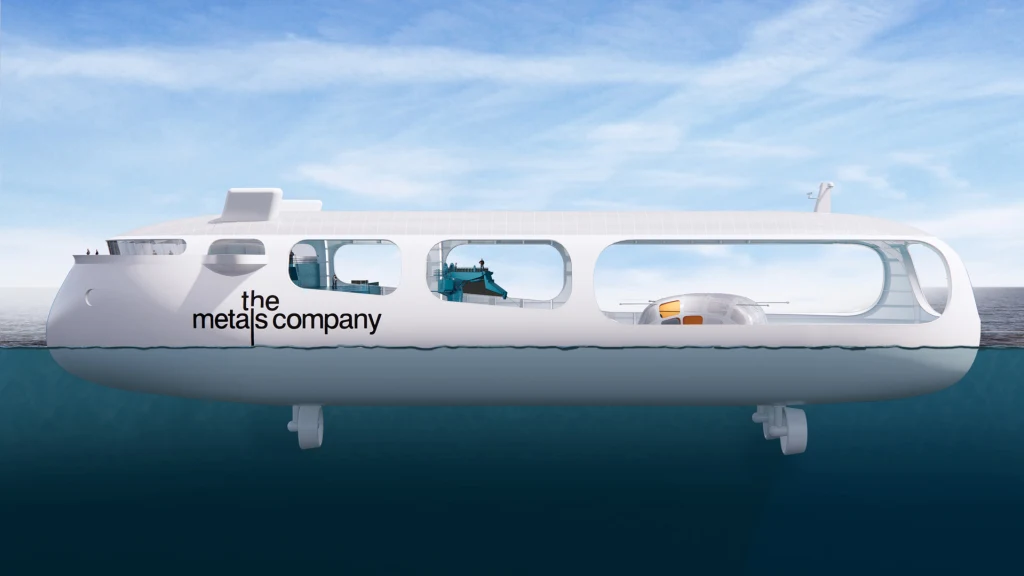

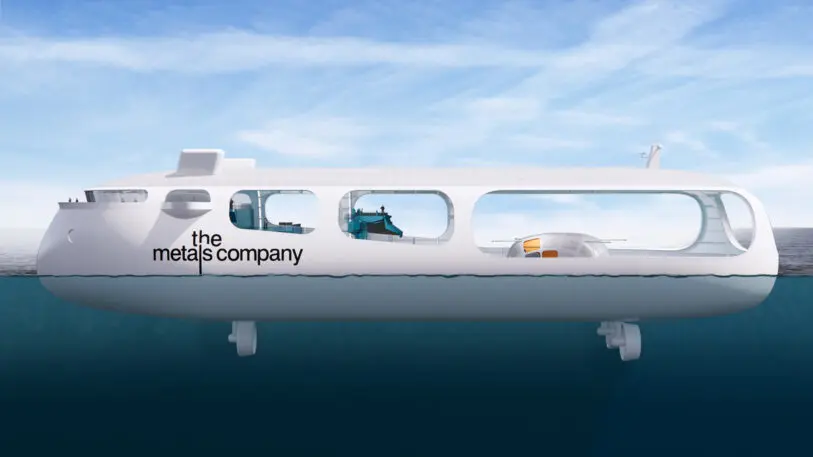

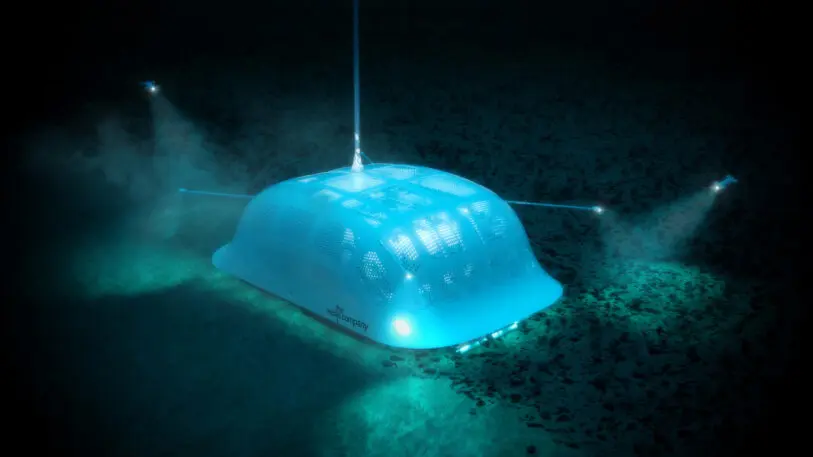

Ingels says his firm’s concept sought to bring a greater sense of design to the mining and processing of these metals as a way of acknowledging their importance to the future of life in an energy-consumptive society. Instead of industrial facilities that are purely utilitarian, he wanted the project to feel like it was meant to be seen, from a horseshoe-crab-shaped mining robot to ovoid surface vessels.

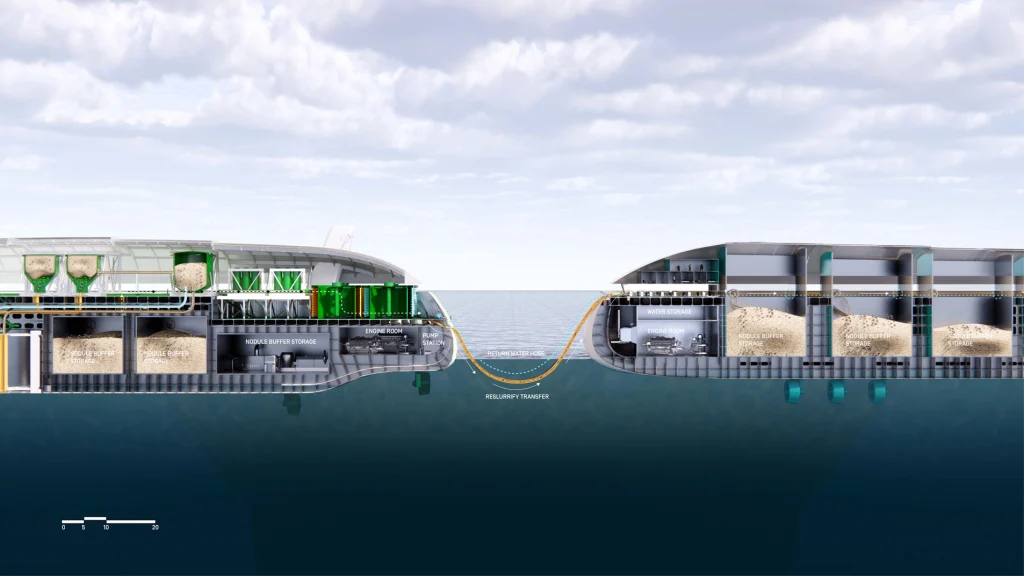

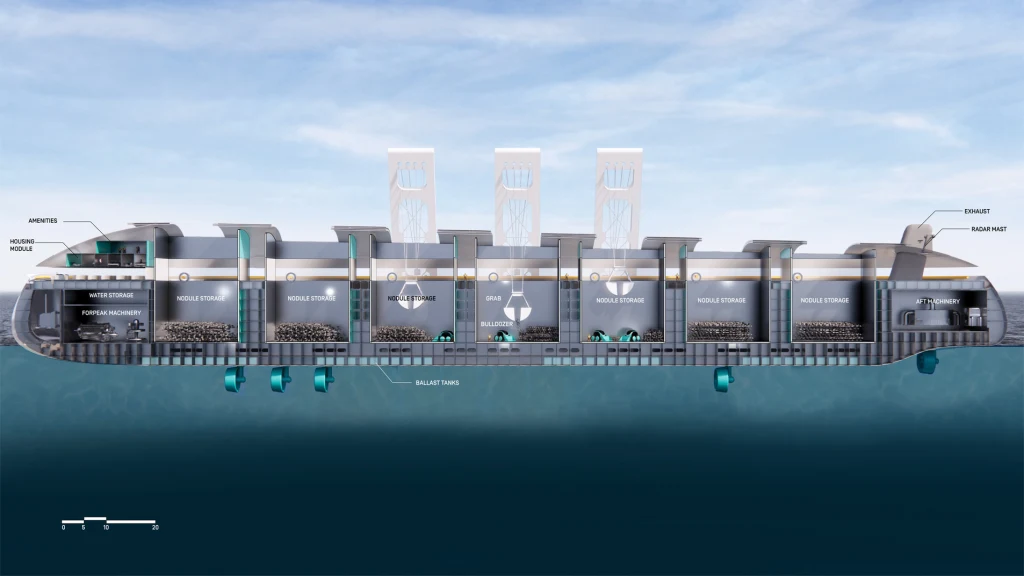

The actual harvesting of the metal-rich nodules involves deep-sea robots that blow a jet of seawater to dislodge the rocks from the seafloor, sucking them up into the collector vehicle and then pumping them up to the surface through a long hose. A production vessel at the surface would then collect and sort the nodules, and then move them onto shuttle carriers that would ship them to one of the port-based production facilities the company hopes to build. Ingels says the robotic collector vehicle was designed with a gentle lip around its edges to control the blowing of sediment during the mining process, a feature that he says makes it look like “a friendly ghost gently hovering above the surface.”

Compared to terrestrial mining, deep-sea mining can be less destructive. But it’s not without environmental impacts, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature. The organization declined to comment on the specifics of the Metals Company’s proposed project, but it’s wary of deep-sea mining in any form. “A wide range of scientific studies have concluded that deep-sea mining without serious harm is impossible. We haven’t seen any evidence that suggests otherwise from this project or others,” says Kristina Gjerde, IUCN senior adviser on the high seas.

Barron frames his company’s effort as an essential part of the global transition to renewable energy. “Certainly I’m of the view that extractive industries have to stop one day in the future,” says Barron. “But before that can happen, we need to have a massive injection of these important base metals in order to build batteries, because of course once they’re in the system, they will be recycled for generations to come.” For now, though, recycling batteries is still complicated.

The Metals Company has rights to explore for these metallic nodules on what it describes as 0.06% of the ocean floor, and its efforts are being sponsored by the island nations of Kiribati, Nauru, and Tonga—low-lying countries that are facing existential threats from climate change and sea-level rise. As members of the International Seabed Authority, their sponsorship is required for a non member to obtain exploration contracts, and they will receive royalties from The Metals Company’s future production.

Hiring a high-profile architecture firm such as BIG is also part of the company’s effort to show that it can be a different kind of extractive industry. Ingels says the design was meant to counter the typically negative perception of industrial activity. “You can send an entirely different message quite easily by thinking a little bit more about the spatial and visual impact of how you put these elements together,” says Ingels. “For the entire onshore facility, we tried to just sit carefully and really understand the journey that the metals go through as they arrive in nodules and then get refined and separated into the different elements.”

Barron recognizes that the company’s proposition may be a hard sell for some. “Not too many people want to be associated with mining,” says Barron. “It delivers fantastic economic results, but we want this to be cool. We want to be a metals company that people actually want to be associated with.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.