Okay, I’ll admit it. I’ve bought furniture on impulse or out of desperation without thinking about its environmental impact. That rickety $150 Ikea bed I used for only two years in grad school. The $99 Target bar cart I picked up while shopping for a party. The $75 Wayfair lamp that completed my living room.

I’m not alone. Since the 1990s, the American market has been awash with inexpensive home goods made in low-wage overseas factories, designed to last only a few years. This affordable furniture makes it possible to redecorate regularly and live itinerant lives, since we can toss everything out with each move. But the convenience comes at a great environmental cost. Making and shipping a single piece of furniture emits an estimated 90 kilograms of carbon, the equivalent of flying a Boeing 747 for an hour. And Americans throw out 12 million tons of furniture annually, up from 2 million in 1960, which clogs our landfills and wastes the wood, metal, and plastic required to create it.

There are still major obstacles to selling secondhand furniture at scale, from shipping to curation pieces. But if resale takes off, it could provide an attractive alternative to all the cheap, disposable furniture that has become so widespread.

The Hurdles to Selling Used Sofas Online

There has always been a market for used couches and dinner tables. In the past, consumers could find these items at Goodwill and vintage shops or, at the higher end, at antique stores. Starting in the mid-’90s, platforms such as Craigslist and eBay made it possible to shop some of these items online by scrolling through grainy images of products that sellers uploaded. But until now, resale has only been a tiny fraction of the overall market: One report found that in 2017, $9.9 billion worth of secondhand furniture was sold, compared to $480 billion of new furniture. For entrepreneurs, this presents an opportunity. “Used furniture used to be a cottage business,” says Timothy Stump, president of Stump & Company, a furniture-focused analytics and investment company. “Now, you have bright people curating products on websites and selling it all over the country.”

Maxwell Ryan has been able to see what’s missing in the secondhand furniture market as founder and CEO of the 15-year-old home blog Apartment Therapy. He observed that younger consumers were more environmentally conscious, helping to spur the rise of used-clothing platforms such as ThredUp and Poshmark, partly because they market themselves as more eco-friendly than buying new fashion. He believed young consumers would be willing to buy used furniture too, but existing sites on the market were not fun or easy to use. This spurred him to build Apartment Therapy Bazaar, a site for buying vintage furniture and decor. “Tracking the rise of fashion resale, I’ve been expecting furniture resale to take off for the past five years,” he says. “But selling secondhand furniture is a completely different ball game than selling used clothes.”

One of the biggest problems is shipping. While it is relatively easy to ship used clothes around the country, furniture is very expensive to transport. This is why Ryan believes platforms such as Craigslist and Facebook Marketplace are so popular: They specialize in connecting buyers and sellers who live in the same area. But this means there isn’t always a great selection of products in any given neighborhood. Besides, the products often aren’t attractively displayed, because sellers take the photos themselves. These sites tend to focus on the lower end of the market, catering to people who are looking for a sofa or a desk in a pinch and don’t want to spend too much on it. “These sites are focusing on the ‘used’ piece, which is not that attractive to most consumers,” Ryan says. “They’re not catering to people who are focused on aesthetics or design.”

Ryan was also interested in selling affordable furniture that could compete with fast furniture brands such as Ikea and Target. But there are only a handful of mass-market brands with recognizable brand names, such as Pottery Barn and Crate & Barrel. The majority of secondhand products available on the market comes from unknown manufacturers who sell their products through retailers. On used-clothing sites, consumers can filter products by brand, but it’s harder to do this with furniture. “The fashion industry is completely dominated by brands, which designate the style and the value of the product,” Ryan says. “There’s a whole language of design around clothing that doesn’t exist as strongly in the furniture world.”

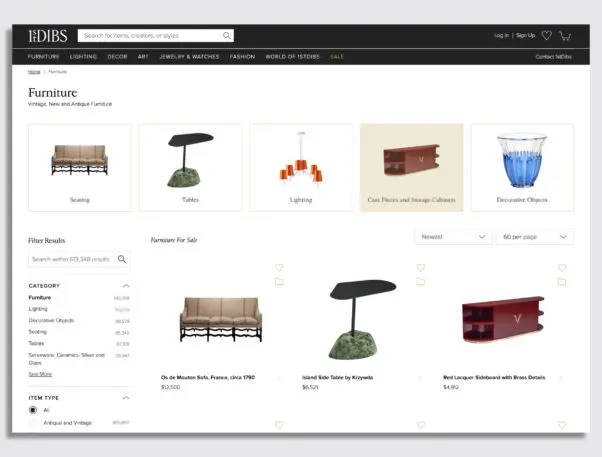

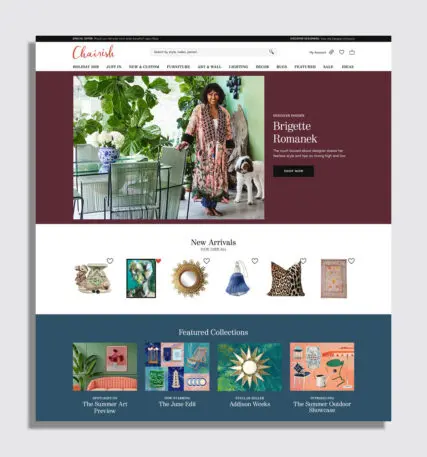

Modernizing Antiquing

It has been easier to tackle some of these problems on the pricier side of the used-furniture market, which is why high-end vintage sites have been growing so quickly: 1stDibs landed $76 million in VC funding in 2019, and Chairish scored $33 million in 2020. Anna Brockway, who cofounded Chairish in 2013, says some of the hurdles Ryan lays out disappear in the luxury segment. Customers can search for products by iconic designers—Paul McCobb, for instance, or Milo Baughman—or by a specific historical period, such as the 1960s. And since the average price of these pieces runs in the thousands of dollars, there is enough of a markup to pay for shipping and still make a profit. Chairish now has 3.8 million shoppers a month, who browse more than half a million products.

Brockway says that Chairish grew very quickly during the pandemic, with sales increasing between 70% and 120% every month compared to the year before. The lockdowns spurred people to upgrade and redecorate their homes, she says, and some people also had more disposable income, since they weren’t traveling or eating out, which allowed them to invest in pricey new furniture. The analyst Timothy Stump believes that some of this new consumer behavior will stick. “COVID proved to many consumers that it is easy to buy online,” he says. “We estimate that it’s accelerated the shift to online shopping by 10 years.”

The Middle of the Market

From Ryan’s perspective, there are solutions for people who want to shop vintage furniture and those who want cheap, used furniture from places such as Goodwill, but the middle is still untapped. His goal is to create a marketplace that sells stylish, design-forward pieces that can compete with fast-furniture pieces on price—but are better quality and more sustainable. Ryan believes that this is the largest segment of the furniture market, and it’s also where there’s the most potential for impact when it comes to sustainability. “Most people go to a place like Ikea where they know they’re not going to spend too much and can get something that looks pretty good,” he says.

For now, the best place to buy a midpriced piece of used furniture is at design-oriented brick-and-mortar boutiques that have started selling some of their pieces online. At Bi-Rite Studio in Brooklyn, you can get carefully curated 20th-century design objects for under $50, in addition to furniture by the likes of Joe Colombo and Mario Bellini for a few hundred dollars. Machine Age in Boston curates original midcentury furniture that is refurbished in-house and sold at prices that are more affordable than what you might find at luxury design stores in New York or Stockholm. “Eighty percent of our sales now come from our website from people searching for vintage furniture on Google,” says Norman Mainville, who opened Machine Age in 1991. “We have many customers in their 30s and 40s who are looking to invest in durable pieces, since it’s hard to find quality like this anymore.”

View this post on Instagram

Ryan is trying to create a digitally native version of these curated boutiques. As he builds out Apartment Therapy’s Bazaar, he’s learning from higher-end marketplaces such as Chairish. These sites are more enjoyable to shop because the products are organized by designer or aesthetic and are beautifully photographed. Right now, the images on Bazaar are uploaded by sellers, but he’s hoping to shift away from this soon by investing in technology that will allow the company to edit these images digitally. And given that there are fewer brand names on Bazaar’s platform, Ryan says it’s important to create a highly curated experience on the site. “We’ve all been to a stylish, vintage furniture store where the owner has a specific point of view,” he says. “That’s what needs to exist in the middle of the market. You need a site where you can see many different brands that go well together and create a particular look that’s appealing to the customer.”

For the time being, there aren’t any marketplaces that accomplish what Ryan is setting out to do at a price point that competes with Ikea, Wayfair, and Target. But in a new development, some furniture brands are creating channels to sell their own products. Ikea, for instance, has announced that it is buying back customers’ old furniture in many markets, including Japan and the United Kingdom, and expects to make this service available in the United States sometime in the future. Depending on the condition of the piece, customers can get up to 50% of the retail price back as store credit. Startups such as Sabai and Floyd now buy back products, which they refurbish and resell. This mirrors a trend in the fashion industry, where established brands such as Eileen Fisher and Patagonia have similar buyback programs. The approach helps consumers who are already familiar with a brand and may want to buy a specific product. The problem for startups is that it could take years to build up enough inventory to scale these programs, since they’re relying on their own customers to sell back used products to them.

The furniture industry still has a long way to go toward making secondhand furniture mainstream, but Ryan is hopeful that change can come quickly. Again, he looks to the fashion industry for comparison. A decade ago, you’d have to go to a thrift or consignment store to buy used clothes, or else scan through listings on eBay. Today, there are secondhand fashion sites that cater to specific segments of the market, from Rebag, which sells luxury purses, to ThredUp, which sells used fast fashion. These companies have also proven there is a lot of money to be made in resale: Both Poshmark and ThredUp have had successful IPOs over the past year. “Fashion resale sites had to solve many problems before they could grow,” he says. “But now they’re thriving and giving the fast-fashion industry a run for its money. It’s only a matter of time before the same thing happens with furniture.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.