In January 2021, prominent software engineer Tracy Chou opened up registrations for her company’s first product. The service—like the company, called Block Party—is designed to help people who experience harassment online, starting on Twitter but with the ambition to expand to other platforms. By giving users more control over what they see on Twitter, Chou is hoping to solve one of the biggest and most intractable problems with social media.

The problem is also deeply personal. “I have some dedicated harassers who are proud to have been harassing me for six or seven years,” says Chou, who grew up in Silicon Valley as the child of Taiwanese immigrants. “Platforms are really bad at detecting this and don’t really care.”

Chou’s experiences with online abuse began when she was in high school, she recalls, but slowly escalated when she became an early employee at Quora and then Pinterest. While at Pinterest, she published a blog post encouraging tech companies to reveal how many female engineers they employed, sparking a movement toward publishing diversity metrics. In 2016, she cofounded Project Include, solidifying her position as an outspoken advocate for equity and inclusion in the tech industry. But as her profile has risen—she now has more than 100,000 Twitter followers—the more she has been forced to deal with trolls, stalkers, and serial harassers sending her abusive, horrifying messages everywhere she goes online.

“My whole life is oriented around how I can be safe, psychologically, mentally, and physically,” she says.

Now, as Block Party’s founder and CEO, Chou is confronting a new challenge: a well-capitalized competitor offering a free alternative to Block Party. Just a few weeks after Chou opened Block Party to the public, another startup called Sentropy announced a similar product. Like Block Party, Sentropy Protect is designed to help Twitter users manage online harassment by filtering out abusive messages. While Chou ultimately plans to sell subscriptions to Block Party, Sentropy, whose core business is enterprise software, says it plans to continue offering Protect to individual users for free.

Tracy Chou, Block PartyMy whole life is oriented around how I can be safe, psychologically, mentally, and physically.”

The financial disparity between the two companies is stark. Though both launched their consumer products in early 2021 and were founded around the same time in 2018, Sentropy has raised a total of $13 million in funding. Block Party has raised less than $1.5 million, from Precursor Ventures and a handful of angel investors including Project Include CEO Ellen Pao, former Facebook executive Alex Stamos, and former TechCrunch editor Alexia Bonatsos. When we spoke in early March, Chou was her company’s only full-time employee and she’d built most of the product on her own. Sentropy, meanwhile, has a team of 26.

For some in Silicon Valley, news that Sentropy would be competing with Block Party touched a raw nerve. “It is harder as a woman of color to raise money and it’s wild to have watched @blockpartyapp_ get to market with these tools first and get less money and fanfare than this move,” tweeted Karla Monterroso, the former CEO of nonprofit Code2040, after Sentropy launched its consumer product. “Competition in this space is good for all of us. But I’m so struck by the difference in funding and coverage when the founder is an impacted woman of color side by side with a white man.”

Chou describes the situation even more bluntly. “It’s such a rigged game,” she says. “I’m going up against people who have 10 times the amount of funding.”

While Block Party is a consumer product designed by and for people being harassed online, Sentropy’s consumer-facing rival, Sentropy Protect, was developed by repurposing the company’s AI enterprise tools. Other startups building enterprise tools to combat online abuse, including Spectrum Labs and L1ght, also raised eight-figure sums in 2020.

“[Enterprise] software-as-a-service businesses trade at higher multiples and make more money,” says TaskRabbit founder Leah Solivan, who is now a general partner at Fuel Capital. “That’s the nature of things.”

That doesn’t make the competition any less difficult for Chou, for whom online abuse is personal—and who believes that this first-person understanding is necessary to actually solve the problem. While Sentropy and other abuse-management startups court business customers, Chou says she decided to focus on individual users because she’s seen how big platforms such as Facebook and Twitter—which, like Sentropy, employ machine learning to filter hateful content—have repeatedly failed people like her.

“It was a big pain point, having to see [abusive posts] in the first place, and a huge weight on my mental health,” Chou says. But because of the threats to her safety, she also didn’t have the option to just ignore it. What she really wanted as a consumer was a way to cordon off the harassment so she could handle it when she was mentally prepared, rather than deal with abusive messages consistently disrupting her day.

Block Party is helpful because platform-level solutions still put the onus on the harassed to block, mute, and report abuse, which for high-profile people like Chou can range from a steady trickle to a deluge. That’s one reason Chou decided to build a product for the people who experience abuse rather than the enterprises that host it.

She also believes that enterprise-first approaches misunderstand how companies think about harassment in the first place. “I don’t think it’s as promising from a market and business perspective, because companies think of abuse as a cost center—something they have to spend money on but it doesn’t make them money,” she says. “Companies would rather pay less than more.”

Even Sentropy seems to have realized some of the limitations to an enterprise-only approach, since it decided to launch a consumer product as well. “Users rely on the companies to always have their safety interests in mind. We think we can be the safety layer that sits between users and platforms,” says Sentropy COO Taylor Rhyne. His vision for Protect is similar to Chou’s for Block Party: “You set [Protect’s settings] one time, and we consistently moderate content wherever it’s coming from.”

The cost of building for users

Not everyone buys Chou’s argument that a consumer-first approach is superior, or even worth funding. For instance, she says that investors at the prestigious startup accelerator Y Combinator discounted Block Party because they believe the platforms are already solving the problem of online harassment using machine learning.

“Some folks are skeptical because they think of the problem we’re working on as ‘niche’—what YC said, for example—and that we have a small potential customer base,” Chou says. “[But] we’ve actually seen much wider applicability of our most basic product than even we anticipated.” (Y Combinator did not respond to a request for comment.)

While Chou initially expected Block Party to be most useful to people with large social followings, she says the product also has users with fewer than 100 followers on Twitter. “There are also people who’ve purposefully stepped back from social media because of the toxicity who are comfortable reengaging now with Block Party as a protection mechanism, so it’s a bigger market than can be seen by just looking at how many users have x number of followers on Twitter, Instagram, etc.,” she says.

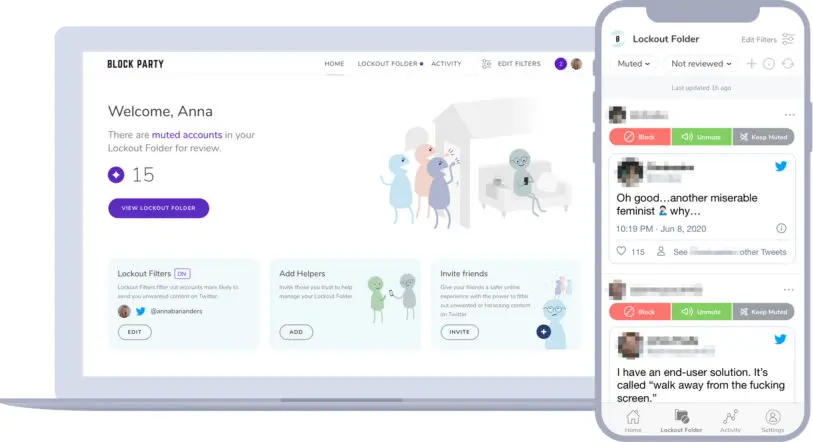

For now, Block Party is free to use, though Chou plans to introduce a subscription tier in the future with additional features. Because the service’s beta launch in 2020 was hit with a denial of service attack and its waiting list was spammed with abuse, interested users are now individually screened and need to wait a short period of time before they’re admitted to Block Party. Alternatively, they can pay an $8 “anti-troll toll” to get access to the platform immediately.

Tracy Chou, Block PartyWe’ve had a number of people ask us how they can pay more, because they are getting a lot of value out of the service.”

Already, Chou says, she’s seen positive signs that consumers are willing to pay for Block Party. She says that between one-third and one-quarter of signups pay the $8 fee even though they could wait to access the product for free. “We’ve had a number of people ask us how they can pay more, because they are getting a lot of value out of the service,” she says. She’s also heard from organizations that are interested in purchasing access to Block Party for their staff.

It’s no surprise that Chou’s investors are predominantly composed of people who are also likely to be intimately familiar with online harassment and its impact. Pao, for instance, became the interim CEO of Reddit in 2014 and faced intense attacks from the service’s users after banning some toxic communities known for harassment. She later resigned. Pao is also outspoken about inequity in tech: She lost a high-profile gender discrimination lawsuit against VC fund Kleiner Perkins, and now serves as the CEO of Project Include, which she cofounded with Chou.

After Block Party’s pre-seed round, however, Chou says she’s struggled to raise more funds—and having a direct competitor may have made matters worse.

The tensions between the two startups spilled out into the open in early February, when Chou and Ohanian clashed on Twitter over whether Sentropy had pivoted to go head-to-head with Block Party. Chou shared an email from Sentropy CEO John Redgrave, from a year earlier, assuring her that his company was taking a “complementary” approach; Ohanian countered that this was still the case, given that Sentropy’s core business remains enterprise. In a separate series of tweets alleging bias in the venture capital world, Chou noted that Ohanian had invested $2 million in Sentropy before it had a working product—more than all the money she’s been able to raise so far.

Ohanian has said he was not aware of Block Party when he invested in Sentropy. When reached for comment, Ohanian said he led Initialized Capital’s 2018 investment in Sentropy because he believed “a very strong AI/ML solution [would] be needed to curb hate and harassment online,” and that he’d been looking for a “team with deep [natural language processing] experience who was also mission-driven around this problem.” He says the company had some rough models and a prototype built when he invested.

Redgrave was equally diplomatic when asked to respond. “I think our approaches to the problem are different,” he says. “I think more importantly, those working in trust and safety need to work together. I think the problem is much bigger than any one of us can solve.”

The focus on enterprise

In contrast to Block Party being grounded in Chou’s personal experiences with abuse, Sentropy’s new consumer product grew out of its roots as an enterprise firm helping companies manage their platform’s abuse problems. Its four cofounders—three men and one woman—have a track record. In 2017, the startup where they all previous worked, Lattice Data, a machine learning company that had spun out of a Stanford lab, was acquired by Apple, reportedly for $200 million. Soon after, it was time for a new project.

Rhyne says he and Redgrave “started thinking about what tech we could build around online gaming. As we started going out and talking to people in different corners of the gaming world, it became clear [harassment] was a blocker like very few other problems.”

Taylor Rhyne, SentropyIt became clear [harassment] was a blocker like very few other problems.”

Redgrave, Rhyne, and CTO Michele Banko collectively cite their own experiences and the experiences of loved ones with online harassment, as well as a desire to make a positive impact on society, as motivation for Sentropy. Still, based on our interviews, Sentropy’s cofounders have a more limited personal connection to the problem than Chou. “This was not the thing we were most immediately drawn to. It wasn’t as obvious to us as it is now,” Rhyne says.

Sentropy’s technology, which uses AI to understand the context of words and account behavior to detect if a message is abusive, was first deployed in two business-to-business products designed for platforms that don’t have colossal engineering teams dedicated to the problem of harassment. Sentropy declined to name any customers but says it is working with dating and social media companies as well as outsourced content-moderation operations.

After launching its B2B products in 2020, Redgrave says that the company started getting requests to use its algorithms from individuals who deal with online harassment. He says a prominent woman of color celebrity asked for access to Sentropy’s tech to help her manage abuse on Twitter.

[Animation: Sentropy]This prompt led Sentropy to take the machine learning models in its enterprise products and repackage them into a consumer product called Protect, which launched in February 2021. Protect detects and flags problematic content and allows users to block or mute specific users or content themes. The product also provides a way to add keywords that should always be filtered out. Certain features are slightly different from Block Party, but the concept and implementation are largely the same. Sentropy says it plans to offer Protect for free for individuals to use. The company may eventually sell Protect subscriptions to businesses, like sports teams and other organizations, but Redgrave says that’s not currently Sentropy’s focus.

Despite the company’s new consumer product, Redgrave says Sentropy isn’t pivoting in that direction. “The enterprise is very much still our focus,” he says. “We believe that going after enterprises would be the best way to address this problem at scale.”

Blasting through walls

While Chou has faced challenges in the traditional fundraising sphere, she also has some distinct advantages.

“The founders that are purpose-built for their opportunities are really passionate about what they’re building,” says Solivan, the Fuel Capital investor. “That passion helps drive the momentum and the scale that’s required to build a sustainable and exciting business. [Chou is] going to hit hurdles, she’s going to hit walls, and she’s going to find a way to blast through them like no one else would for that particular problem.”

Chou, after all, is building a product that will solve her own problem—and a problem for many women, LGBTQ folks, and people of color who are outspoken online. Despite the millions invested by platform companies aiming to combat it, harassment is simply part of being on the internet for many people.

[Animation: courtesy of Block Party]“I’m somewhat newly out as trans and that has led to a massive increase in the amount of hate that I’m receiving on Twitter,” says Jaclyn Moore, the showrunner for Dear White People on Netflix and a Block Party user. Moore decided to try out Block Party to manage the abusive message she was receiving. “I set it up once, I set up my filters, and then I could go back to Block Party and review the mutes that it does automatically,” she says. “But if I didn’t do that, I didn’t know I was getting hateful anything. I had no idea.”

That’s by design—and derived entirely from Chou’s personal experiences of being harassed. Rather than using machine learning algorithms to try to assess the intent of a tweet, Block Party’s analysis is based on the characteristics of each account that is interacting with you on Twitter. You first set your filtering settings, which enable you to decide what types of accounts to mute. For instance, you might just want to see comments and responses from people you follow and people who follow them. That means any new accounts, any accounts without profile pictures, and any accounts with fewer than 10 followers—all signals that an account may be used for harassment—won’t ever make it to your notifications and will instead stay in the Lockout Folder.

“Maybe it caught a couple people out of a hundred that were people saying nice things but we didn’t follow each other. That felt like such a small price to pay,” Moore says. “This is such an elegant solution because it doesn’t require your attention.”

Jaclyn Moore, showrunner, Dear White PeopleThis is such an elegant solution because it doesn’t require your attention.”

One benefit to this approach is that there’s a wide range of content that doesn’t actually violate a platform’s terms of service or wouldn’t necessarily be flagged by an algorithm as overtly racist or sexist, but is still unpleasant and mentally taxing to see during daily online life. “There’s plenty that doesn’t need to be deplatformed—insults, mansplaining,” Chou says. “But I’d like more control over if I see it or not.”

Block Party’s focus, for the time being, is on Twitter, in part because the platform has a long-standing harassment problem and because its API (application programming interface) is open enough to support Block Party muting accounts on a user’s behalf. Ultimately, however, Chou wants Block Party to become the API for safety across the entire internet, similar to how Stripe has become the ubiquitous API for payments. Rather than her company needing to court the big platforms, Chou’s ambition is that platform companies will integrate with Block Party. For users, the service could become “that preferences and filtering panel wherever they go online,” she says.

It’s a sweeping vision for what Block Party could become. But for Chou, the fundraising challenges she’s facing represent a barrier to Block Party’s future—despite her conviction that she has the technical expertise, personal experience, and passion to build the product into a successful startup. “The lack of diversity, representation, inclusion, equity, and commitment to these issues all through the [startup] ecosystem means we’re going to keep not solving problems that are just getting worse,” she says.

While Chou believes her company could become a profitable business, at the end of the day she says she cares more about combating online harassment than about her individual success. “If someone solves this and that’s why Block Party doesn’t exist, that’s fine,” she says. “I don’t want a scenario where copycats put us out of business, and then they don’t understand the problem, and the problem is not solved. I want this problem to be solved.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.