Giant 3D printers for construction can help make housing more affordable—as in a neighborhood in Austin, Texas, where a 33-foot-long machine recently squeezed out the walls of tiny new houses for people who were once chronically homeless. But an Italian architecture firm is experimenting with a way to potentially make the process even less expensive, and better for the climate, by using a cheap and readily available building material: local soil.

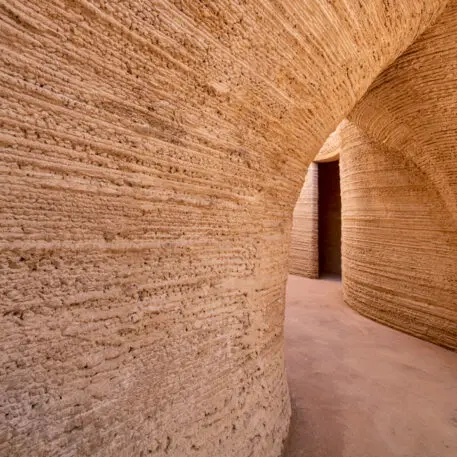

The process works by excavating soil, removing stones and gravel with a sieve, and then mixing the dirt with water and rice husks in a concrete mixer, which makes it solid enough to form walls. The printer squeezes out the mix through a nozzle that stacks thin layers to build the walls. The new home, at around 645 square feet, took around 200 hours to print, though the process will move faster in the future.

The domed shape of the home makes it structurally strong, he says, and thick walls help provide insulation, while a skylight at the top of the dome brings in extra light. The team now plans to do performance tests and explore variations on the design, including a two-story building. It hopes to share the solution widely, including in low-income countries. The design can be adapted based on the local soil and local climate. “The idea is not to have the same house everywhere, because the machine can print any kind of house,” he says.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.