By 2035, the city of Helsinki plans to be carbon neutral. But in a part of the world where the average winter temperature is a few degrees below freezing, one challenge of reaching that goal is heating hundreds of thousands of homes without using fossil fuels (or burning wood, which the city doesn’t see as a long-term solution). Because the city recognized a need for new innovations in heating technology, it sponsored a 1 million euro reward, the Helsinki Energy Challenge, for anyone who could come up with a viable alternative.

Water efficiently stores heat, and this type of thermal storage “has been used before, but never at this unprecedented scale,” says designer Carlo Ratti, founder of the international design and innovation office Carlo Ratti Associati, which developed the proposal. “Also, the concept of floating reservoirs is new and could be a game-changer. It could theoretically be used in any coastal city—facing the sea, lakes, or rivers.”

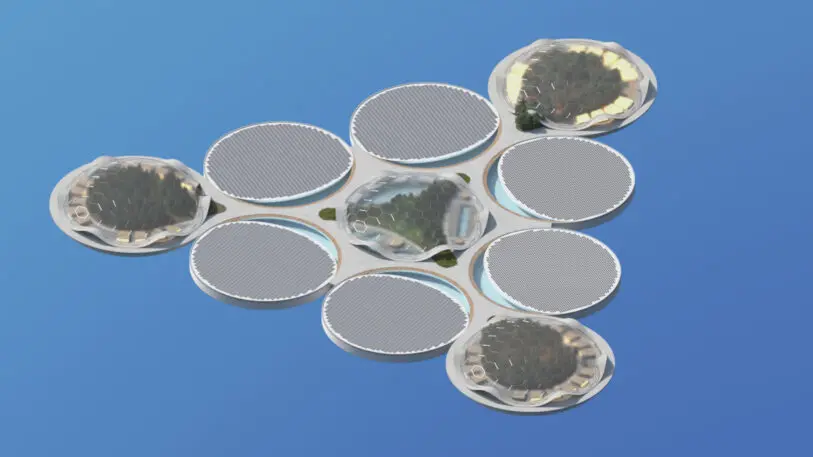

[Image: Squint Opera/courtesy Carlo Ratti Associati]The system would use renewable electricity—at times of day when it’s most abundant and least expensive—to run heat pumps that would heat the seawater and store it in the reservoirs. Whenever the heat is needed, it would be sent to Helsinki’s district heating system, an existing network that sends heat to almost all of the city’s buildings. Four of the 10 reservoirs would have roofs and would be open to visitors, taking advantage of the heat to grow tropical plants and offer heated swimming pools.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.