Amira Rasool is founder and CEO of The Folklore, an online concept store featuring contemporary African design. She spoke to Doreen Lorenzo for “Designing Women“, a series of interviews with brilliant women in the design industry.

Doreen Lorenzo: How did you first find your way into design?

I also always had on these funky outfits, so my older sister Jasmine told me: “Why don’t you just get into fashion? You watch The Devil Wears Prada all the time. You’re always getting dressed up. You like writing.” She suggested that I start a blog back in 2010 when blogging was really big. So I created a blog and an alter ego named Bobby Austin posting outfits of me wearing purple wigs and black lipstick. I also started taking FIT (Fashion Institute of Technology) pre-college courses, so all my friends were just as weird as me and also had wigs on. I grew up in South Orange, New Jersey, about 40 minutes outside of New York, so I would take the train on the weekends, do my college courses, then go hang out with my friends afterwards. I was one of those weird creative kids that was also a great athlete, and could fit into both worlds.

What made you decide to go from creative fashion blogger to entrepreneur and founder of The Folklore?

The blog is what let me know that my passion was in writing. I started doing internships as soon as I got into college floating between interning for fashion market editors, stylists, and features editors. I interned at Women’s Wear Daily and I really loved that experience. From there, I went to Marie Claire, which was really eye opening for me because I was given a lot of responsibility. It made me understand how hectic magazines were and learn how to take charge without anyone telling me to. I realized I was super good at organizing and providing top-quality results. My boss from Marie Claire then referred me to V Magazine where I interned in their fashion department, and later their editorial department.

During my internships I made really good connections with the people I worked for. They saw I was a hard worker. By the time I graduated, I had multiple magazine jobs that I was up for. People in media know it’s so hard to get that entry-level job when you’re coming out of college. The fact that I had my choice between jobs was a testament to me busting my butt and always being reliable. I ultimately ended up choosing V Magazine where I worked full time for a year as their fashion coordinator before I decided to start The Folklore.

When I was majoring in journalism at Rutgers, I started taking a bunch of African American studies courses. By the end of my junior year, I had more African American studies courses under my belt than I did journalism. I decided to change my major to African American studies. Growing up they did not do a good job teaching us about Black history outside of Martin Luther King, Harriet Tubman, and the few other Black people they let us learn about. So when I started taking those African American studies courses and started learning about so many inspiring people, I was shocked. I became obsessed with Black literature and started reading James Baldwin, W.E.B. Du Bois, Toni Morrison, and a lot of the people who came from the Harlem Renaissance. I learned how the creatives during the time were able to create these great publications like Fire!! that were a part of activism, but more creative activism. I related to that because I felt like I was put on this earth to uplift my people in some powerful way. I had this fire under me to go out and make an impact within the Black community.

I had taken a trip there my senior year of college and fell in love. I went to South Africa and discovered all of these cool designers, creatives, and music. I bought a bunch of clothing and accessories when I was there and started wearing them when I came back to the United States and people were stopping me and asking: “Where did you get those sandals from? Where did you get this hat from?” I started thinking about getting access to these products again, but most of them did not have e-commerce sites and weren’t sold at retailers outside of Africa. I didn’t have access to them unless I hopped back on the plane. That’s when I came up with the idea. Why is there a whole continent full of designers that cannot penetrate the international market, and how can I help them do that? How can I use my resources, network, and overall creativity to find a way for them to have access?

I started creating a business plan and applied to the University of Cape Town for a master’s degree in African studies. Once I got in, I moved to Cape Town, South Africa, and lived there for two years learning about the designers and what they needed from an e-commerce platform. At the same time I got to learn about various African cultures. That informed how I thought about communicating these designers’ stories. Halfway through my program I ended coming back to the U.S. to launch The Folklore site.

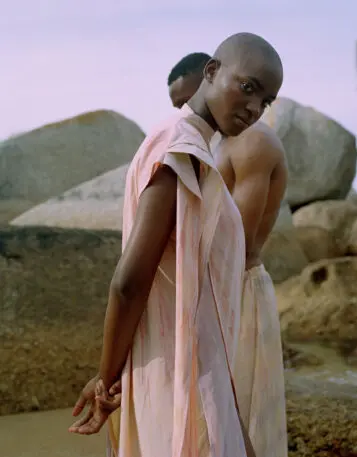

There’ve always been so many different stereotypes of Africa. There’s definitely poverty in Africa, but at the end of the day, that’s not the only Africa, and Africa is not the only place with widespread poverty. For a whole continent to be defined by that is ridiculous. I wanted to be able to reflect that and show this whole renaissance happening with designers incorporating their heritage into modern and contemporary forms of expression.

Being on the continent was really important because I was able to touch and feel the fabrics and most importantly, connect with the designers. I knew I wanted to stay away from Ankara prints or anything traditional because I wanted everyone to be able to wear these pieces. I wasn’t going to be the American that came in and started selling white people Ankara prints, advocating for cultural appropriation. I also did not want to be a cultural appropriator myself, so I purposely go after pieces that can be worn comfortably by anyone.

There was already a market that catered to Black people who wanted to feel connected to the continent and their cultural heritage. I wanted to provide that counter-narrative where someone could see a piece and not know where it was created. People universally can wear these products and we know the only reason why these designs are as unique as they are is because of these designers combining their heritage, culture, and their natural environment in Africa that’s not typically portrayed. When you don’t know that this place exists, everything’s going to look new and unique to the outside person. I’m excited to be the person to help the designers introduce this counter-narrative and share their unique stories outside of Africa.

It means a lot. The network, resources and overall knowledge Techstars provides is extremely beneficial. I like to think that when The Folklore got into TechStars all of our brands got Techstars. Whatever knowledge or resources we absorb during the program, we are going to make sure we share with our brands. One of Techstars’ mission statements is “Give first” and everyone who I’ve encountered at Techstars has really embraced that mission. So much of the focus is how to help you raise money and build a profitable company. That’s a great thing because they realize what it takes to build a great company. Everyone’s been super supportive, so I’m really excited and honored to be a part of it.

This is going to change the way people value Africa and its creators. The value that was placed on African designers before was the amount of clicks their creativity could generate for fashion publications featuring African brand look books. They didn’t care that the press these brands were getting did not convert to dollars because a lot of the brands did not have a website to link back to. It was an afterthought.

We created a dialogue around economic opportunity and put the pressure on the industry to actually put their money where their mouth is. Now they can write about these brands and link it back to The Folklore. We want to put as much value on these designers as people put on Gucci or Alexander McQueen, and honestly, there’s more value in these goods because most of them are unique and sustainably made.

People pay luxury prices because they were told these brands are important. When we’re pricing our goods, it’s really because it costs a lot of money to ship these products from Africa to the U.S. The e-commerce infrastructure has been set up, whether consciously or not, to exclude people like us. If you’re truly committed to diversifying the designers that you work with and fighting for equity and inclusion, you have to make compromises that you would have otherwise not made for more established brands. When you’re paying for a product from our website, you’re buying something because it is amazing. People have asked to donate to my company but no, you can invest in my company, our brands, and their products. We don’t want charity. Nobody wants charity. I want to change the way that people talk about contributing to Africa and help people recognize the value in not only how these products are produced, but in the story and the exclusivity behind them.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.