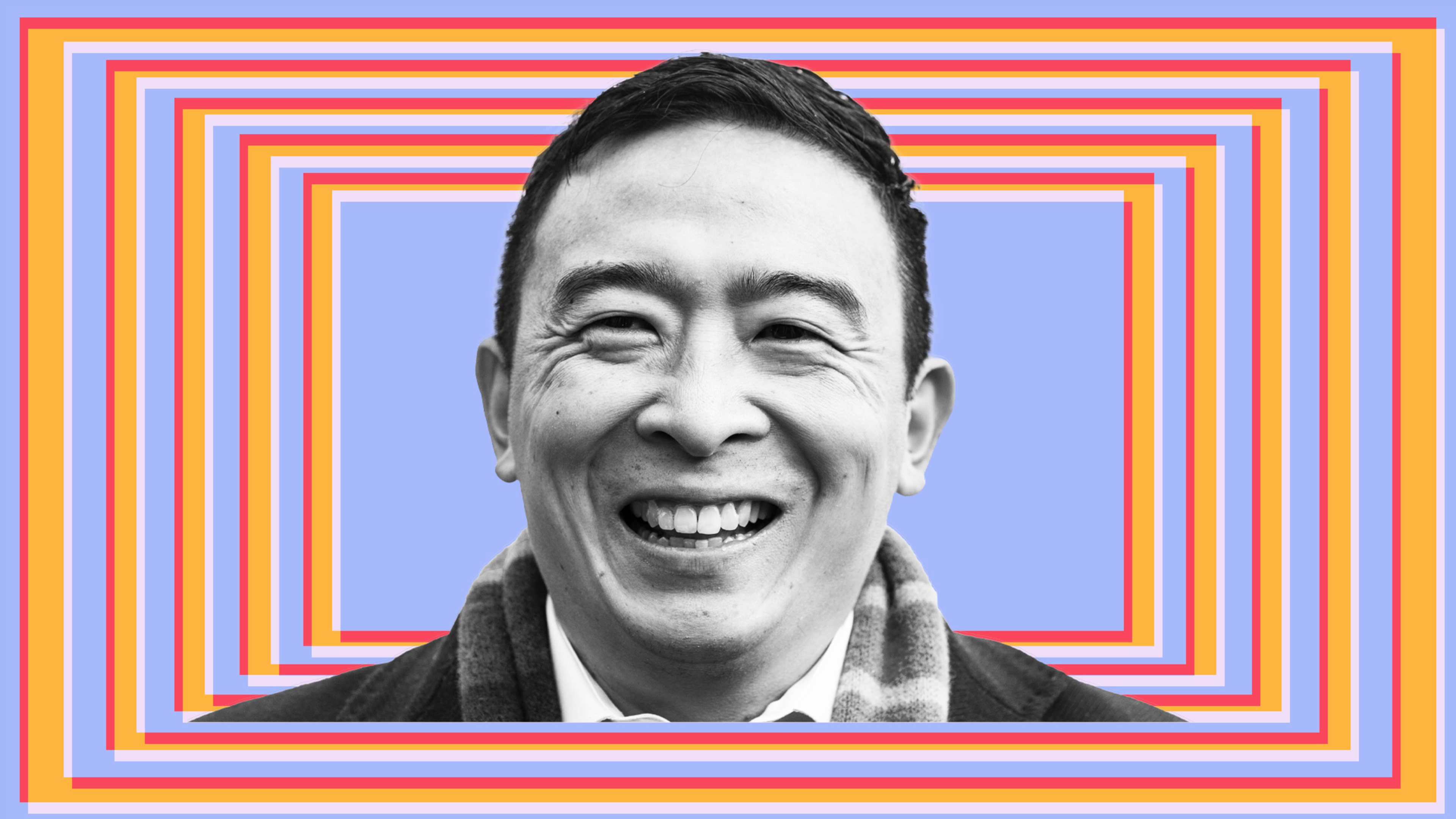

There’s nobody quite like Andrew Yang, the erstwhile presidential phenomenon whose campaign for a universal basic income found an unlikely ally in the Trump White House—and helped lay the groundwork for direct cash payments during the pandemic. He’s a political outsider who loves to be on the inside; a tech cheerleader who worries about artificial intelligence; a progressive who’s not afraid of Joe Rogan; and now a New York City mayoral candidate who’s . . . never voted for mayor.

He’s also a serial entrepreneur, with deep ties to the tech community and strong opinions about how the public and private sectors should cooperate to foster innovation. That’s one of Fast Company’s bailiwicks too, so we decided to catch up with the father of two (and former Fast Company columnist) in New York to discuss the Great Reopening, the future of bitcoin, why Manhattan beats Miami, and the trouble with Zoom.

Fast Company: Congrats on the latest poll. Were you surprised at all to be leading the field with 32%?

Andrew Yang: I’m excited that New Yorkers are excited. I think a lot of people are frustrated with what’s been going on in the city this past number of months and years. We know we need a different kind of leadership. I’m thrilled that people see that we can do better for ourselves. That’s my main mission, to restart the engine of New York’s economy and get the agencies and bureaucracies functioning at a higher level.

Right—the number one thing on most people’s minds right now is the reopening the economy. We’re poised for a massive rebound in economic activity, but there’s a general feeling that the guidance from the government—on schools, restaurants, where and when you can take off your mask—has been confusing and slow.

I’ve talked to dozens, maybe hundreds of business owners here in New York City, small-business owners, comedy clubs, restaurants, bars—and they were very frustrated with the operating guidelines and the lack of visibility. Right now there are different restrictions in New York State as opposed to New York City, which I think made sense at a certain point during the pandemic, but it makes less and less sense now, given the expanded vaccination rates and the fact that infection rates are falling.

So number one is, can you reopen your doors? Number two, can you manage all of your financial obligations, primarily rent? If you were the average bar or a restaurant, you might owe somewhere between 3 and 10 months of back rent, even if your landlord is cutting you a break in terms of your cash obligations. The third thing is that, right now, when people hear from the city, it’s the city checking on compliance with various regulations or showing up to say, Are you doing this right? Are you doing this right? And in some cases even fining small-business owners.

One of the things that we can do better is to have a moratorium on fines and licenses. I think it’s really unfortunate that if you’re a business owner, you hear from three different agencies who all are just trying to make sure you’re complying with various regulations, and no one’s reaching out to you to say, Hey, here’s some resources you can make use of.

You’ve come out in favor of a vaccine passport.

New York City is down 60 million tourists and 82% of commuters. And so even if you say to all of these restaurants and bars and small businesses, You can reopen your doors, there are no customers. And we have to give organizations the confidence that people can come back to the office.

In Israel, they’re past 50% vaccination, and they’ve issued bracelets that essentially say, I’m vaccinated. Imagine it’s like New York City could be a giant VIP area of a club where you get a bracelet saying you’re vaccinated. And then you’d go to the restaurant, the bar, the club, like everything else. I mean, those are the kinds of measures we would need to do to give people confidence to be able to actually show up to a lot of these small businesses that are struggling right now.

This has been a ruthless pandemic. We’ve lost 27,000 lives. Like, it’s been very real. But we also should be excited about some of the data that shows that reopening to higher levels is the right thing to do and won’t pose any additional risks.

You mentioned getting people back into offices. Your second book is about how A.I. and automation are displacing jobs, and obviously COVID has accelerated some of those trends. Are there pandemic-era innovations that you see as a net positive? Or do you worry that remote working, for example, will increase geographic dispersion from cities?

I think it has been underestimated how much technology and artificial intelligence have already transformed the financial services industry, where you have certain tasks that might’ve been done by dozens or hundreds of people a number of years ago that are now being done by software, and then six techies who are tending to that software. I mean, you can see some trading desks have become more automated than human. So those forces are very real. And I think that a place like New York City is a great place to both advance innovation in productive ways, but also try and humanize the economy.

So I’m a fan of progress and innovation. Like, by and large, we should be embracing the things that are making our lives better or helping organizations function better. But at the same time, I am a very firm believer in the fact that in order for a world-class organization to be able to develop the next generation of talent and leadership, there’s just no substitute for bringing people together and having them work together in the same environment. I know this because I’ve lived it, several times in New York City, where I came as a 21-year-old. I’ve been a part of several growth organizations that accomplished some amazing things. And it was because you had a group of diverse, talented people that came together to learn from each other.

And that is, in many ways, the core value proposition of New York City. This is a place where some of the most talented people in the world come together to create, to learn, to live, to enjoy. So when you talk about technology and some of its like pluses or minuses, I try and think of it more as, How can you integrate it in a way that makes sense for both individuals and families and organizations?

I’ll give you an example, with Zoom. A lot of CEOs are very eager to get people back into the office. Like, they don’t think that remote work in perpetuity is the answer, at least for their organizations, but they do see that there are benefits to remote work. So right now they are aiming at having people back in the office, let’s call it three days a week or four days a week. That, to me, is an intelligent approach and the right balance.

There’s been a lot of talk recently about high rollers in finance and tech fleeing New York for states like Texas and Florida. You gave an interview to my friend Bess Levin at Vanity Fair where you said you want to be “the salesperson in chief” for New York. So how do you go about getting these people back?

Oh, I’ll tell you, it’s going to be very easy to get them back to the city to visit, because they come back to the city all the time, or they will as soon as travel is a bit easier and we’ve opened things up. Really, the question is where they’re going to be based for their family purposes, for school. It hasn’t helped that our schools have been closed for months. I mean, that has helped push some folks to another location.

And I’m going to suggest that a lot of people are still figuring it out. If they are earnest about trying to build the next world-class organization, we’ll find that New York City has some benefits that are very, very hard to replicate in another environment. There’s no place like New York City. There’s just a talent density and diversity here. And one of the things that can’t really be replicated is that we are the cultural capital and hub for creatives and artists of every discipline.

But it does start with having a mayor that will say, very unabashedly, that New York City is open for business—that we want entrepreneurs to come build businesses here. And frankly, New York City right now has had leadership that hasn’t seemed very business-friendly.

You’ve said that you want New York to be a hub for bitcoin and cryptocurrency.

To me, it’s common sense. We’re the world’s financial capital, and at this point, cryptocurrencies are a trillion-dollar asset class. You have major New York firms who’ve already started cryptocurrency departments. So you have to make sure that if we’re going to truly utilize blockchain technologies in various settings, that it really should be in New York City. And I have many friends in the cryptocurrency community who are extremely excited about actually trying to apply these technologies.

So, one topic that interests us at Fast Company is how organizations build an innovation culture, whether it’s in the private or public sector. How do you make public service a more compelling career track when bureaucracies are so resistant to change?

I know a lot of technologists and innovators that frankly have made some money and now are looking to have an impact, and right now they’re not attracted to government, because they’re not sure if they’re going to have their hands tied by red tape. And often they’re just not asked. Like, if I am mayor of New York City, I’m going to call some of my friends and say, Hey, we’ve got a giant problem, we’d like you to look at it. And then we’re going to empower them to actually do what they want to do, and find ways to make it work.

Like, obviously we have to operate within the rules and confines of the existing city government, but if we can find an innovative way to deliver a service, then I think that’s exactly what we need right now.

One of the startups you founded is a nonprofit organization, Venture for America, which deals with some of these issues—training recent graduates to work for startups in emerging cities.

I’ve studied innovation ecosystems for years, and the single biggest way for you to produce the next generation of entrepreneurs is to have a firm grow to a size and scale where it goes public, gets acquired, has some kind of major liquidity event. And then all of a sudden, every VP in that company becomes either a founder or an early-stage investor. And New York City has had a whole series of companies go through that life cycle. That’s the way a lot of these innovation ecosystems develop. I think New York City still has untapped potential on that front.

One thing that’s always astounded me about the United States, but New York City in particular, is why we’re so bad at infrastructure and public works. Here you’ve got all these entrepreneurial people, and yet it costs three times more to build a subway station in New York than in London or Paris.

The MTA is vital to the city’s recovery, and if you don’t control the main arteries of transportation, that’s very hard to manage a city. I mean, I’ve been a frustrated New Yorker—when things go wrong on the subway, you look up and say, like, Okay, who’s responsible. And the mayor, legitimately, is like, Well, there’s an MTA board that’s primarily appointed by the state—and you’ve never heard of any of these people! [Laughs.] That’s not a recipe for accountability or success.

If I said, Hey, we’re going to build a new subway station in your neighborhood, you would probably laugh out loud because you would know, best case, that it would take years and years and years. But the opportunities that you have right now are around rapid-transit bus service and new bus lanes, around bike-ability and walkability. I moved to New York City when I was 21 years old, and I did not bite the bullet and buy a car until I was in my 40s and my second child was born.

So to me, this is actually another core aspect of what will make New York City competitive and attractive to talented young people, in particular, is that you have to be able to move to the city and not worry about owning your car. So when you talk about the issues of mass transit in cost, they are very real.

You know, I do have a sense as to why building a subway station is so difficult here, but even as we wait to untangle that, there are other things we can do that will improve people’s ability to get around. I believe there’s going to be a very significant infrastructure bill coming out of Congress. I’m friends with the new secretary of transportation [Pete Buttigieg]. And I want to build things in New York City, and I think we’re going to have the resources to do so.

I did want to ask you about this wave of hate crimes targeting Asian Americans in New York and around the country. What does it mean to you, as you’re running to be New York’s first Asian American mayor? And what would you say to other Asian Americans looking to get more involved in government, where they’re currently underrepresented?

It’s a very difficult time for people in the Asian American community. We’re facing a type of hatred and violence that we never have before. I was at an event with a group of community leaders here in New York City, talking about what we could do. And Jumaane Williams, the public advocate here in New York City, said something that really stuck with me. He said, do one thing each day that will help you connect with other people, even if it’s simply smiling. I mean, you have a mask on, but like, greeting someone that you wouldn’t have greeted otherwise. The message I have for folks, as heartbreaking as this time is, is like, You can’t let fear win. And you have to try and translate this into some sort of positive action.

And that’s what I try to do every single day. But one of the reasons why I’m running for mayor is that I think that the city is wounded, and in a lot of pain, and Hurt people hurt other people. If you are in an environment where you’re down 600,000 jobs, and you’re insecure in your future, then you may lash out at people that are different from you. And that’s one reason why we have to get New York City back on its feet as quickly as possible.

Before you go, we have to talk about the tweets. The controversial bodega visit, the selfies in front of Madison Square Garden, banal descriptions of your subway route—which, depending on your point of view, are either totally, maybe painfully normal, or else some kind of high-concept trolling operation.

I think our social media strategy has just been trying to convey a sense of what we’re doing every day. And convey a sense of energy and vitality that I think a lot of New Yorkers are looking for right now. I will say that anyone who thinks that we have some kind of war room where we figure out how people are going to respond to this tweet or that tweet are giving us way too much credit. Frankly, we’re focused on things we can do to help get New York City back on its feet. But if that’s the way people want to interpret things, you know, we’ll leave it to them.

Fair enough.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.