The first two COVID vaccines approved in the U.S. both use first-of-a-kind technology called messenger RNA. Johnson & Johnson’s new vaccine is different, and the technology it uses may have helped give it two advantages: It only requires a single dose, and it can be stored for months in a refrigerator instead of an ultra-cold freezer.

All three vaccines are based on the genetic instructions for building the COVID spike protein, the part of the virus that invades human cells. The mRNA vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna inject a solution containing RNA into your arm, which instructs your body to begin making a harmless piece of the protein that then triggers the immune system so it can mount a strong response if you later encounter the actual virus. Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine works in a similar way, but stores the genetic instructions in DNA instead. The gene is inserted in a modified cold virus called an adenovirus. The company used the same approach to make its new Ebola vaccine.

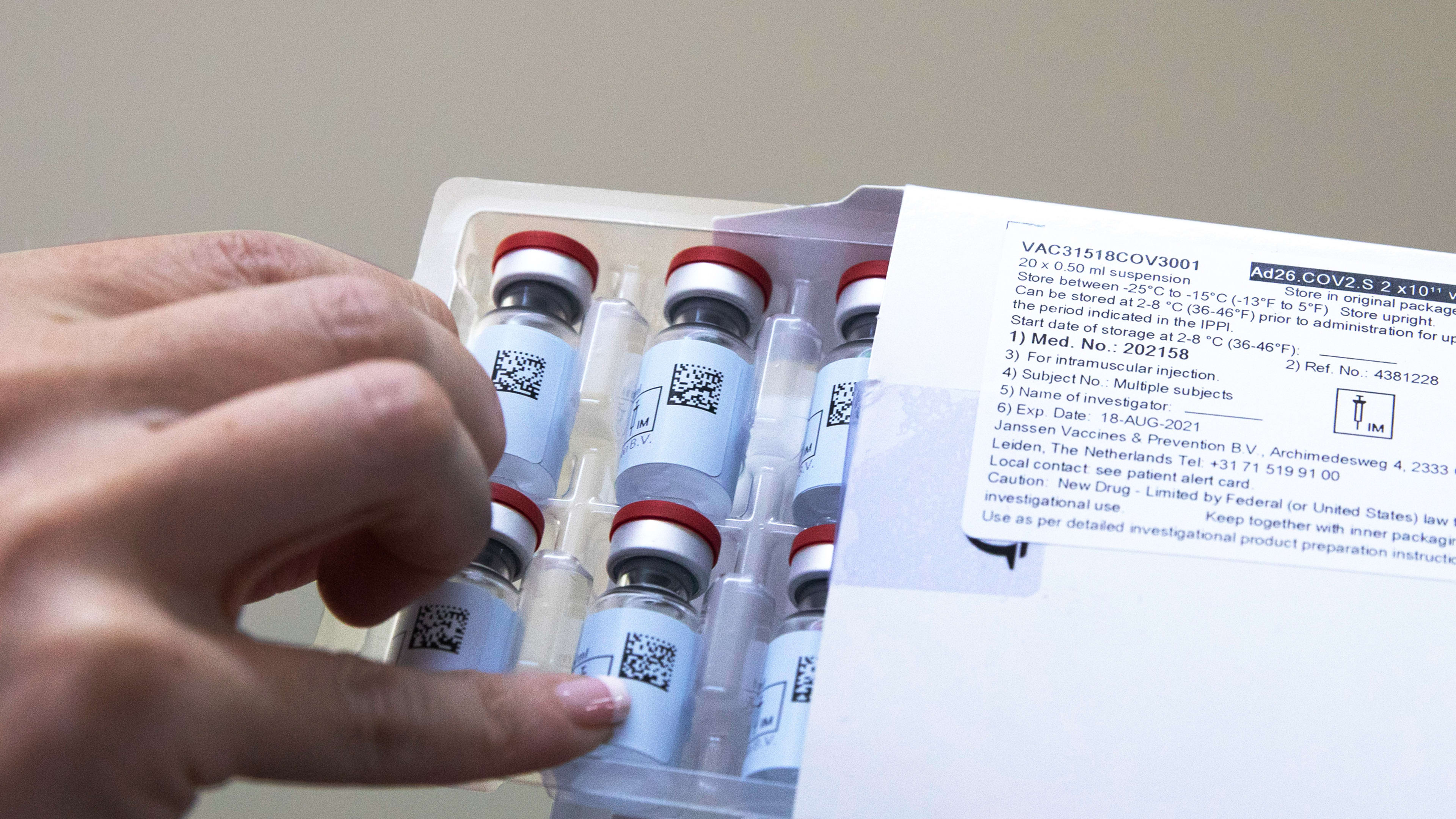

Because DNA isn’t as fragile as RNA, and the adenovirus around it provides extra protection, the Johnson & Johnson vaccine is sturdier than the other vaccines. The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines have to be frozen for long-term storage, but the Johnson & Johnson vaccine can be stored in a regular refrigerator for as long as three months. That makes logistics easier everywhere, but especially in the developing world. “We know that if we can get enough of this manufactured it’ll be much easier to send out into the field, not only in the U.S., but across the globe, which is really important,” says Lisa Lee, an epidemiologist and professor at Virginia Tech who previously worked at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Because this pandemic isn’t over for us until it’s over for everyone.”

The vaccine was also designed to work with just a single shot, another crucial factor that can help speed up the pace of vaccinations. “In other vaccines that we use it in, the adenovirus vehicle tends to really help a person mount a pretty substantial response that that is fairly lengthy,” Lee says. “So we have some more experience with that to know that we can expect enough with one shot.”

The company is now testing whether the vaccine could be more effective with the addition of a second dose, but the initial trial showed that it does work with one. (With more time, it’s possible that both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines will also be proven to be effective enough to use with just one dose instead of two.)

In a global trial with around 45,000 people, the Johnson & Johnson vaccine was 66% effective against moderate to severe COVID infections. That’s substantially lower than Moderna and Pfizer’s vaccines, which are 94% and 95% effective, respectively, at preventing symptomatic COVID infections after two doses. (Vaccine efficacy numbers do not mean that 34% of the people who took the Johnson & Johnson vaccine still got sick; instead its a ratio of people in trial got sick after taking the vaccine versus people who got sick in the control group). The trials of the two vaccines aren’t directly comparable because they happened at different stages in the pandemic. “The Johnson & Johnson vaccine was tested in the reality of the virus variants, while the mRNA vaccines were approved before we believe these variants were circulating widely,” says Maureen Ferran, a virologist at the Rochester Institute of Technology. “I think this might explain, at least to some extent, why the Johnson & Johnson vaccine is less efficacious. Some of the J&J trials were done in South Africa in the presence of a really nasty variant.”

The vaccine was 72% effective in the U.S. portion of the trials (the minimum bar for FDA approval is 50% efficacy at preventing COVID). But more importantly, it was 85% protective against severe cases of the disease across the whole trial. No one was hospitalized or died—and clearly that’s the most critical metric. The new vaccine, along with the others, will help more people survive. It will also help speed up the overall process of immunization.

“The bottom line of all of this is we need to get as many people vaccinated as soon as possible because every time the vaccine or the virus is transmitted, it has the opportunity to mutate, and those variants could potentially do us a lot of harm,” says Lee. “We need to get as much out there as quickly as we can.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.