Timnit Gebru—a giant in the world of AI and then co-lead of Google’s AI ethics team—was pushed out of her job in December.

Gebru had been fighting with the company over a research paper that she’d coauthored, which explored the risks of the AI models that the search giant uses to power its core products—the models are involved in almost every English query on Google, for instance. The paper called out the potential biases (racial, gender, Western, and more) of these language models, as well as the outsize carbon emissions required to compute them. Google wanted the paper retracted, or any Google-affiliated authors’ names taken off; Gebru said she would do so if Google would engage in a conversation about the decision. Instead, her team was told that she had resigned. After the company abruptly announced Gebru’s departure, Google AI chief Jeff Dean insinuated that her work was not up to snuff—despite Gebru’s credentials and history of groundbreaking research.

The backlash was immediate. Thousands of Googlers and outside researchers leaped to her defense and charged Google with attempting to marginalize its critics, particularly those from underrepresented backgrounds. A champion of diversity and equity in the AI field, Gebru is a Black woman and was one of the few in Google’s research organization.

“It wasn’t enough that they created a hostile work environment for people like me [and are building] products that are explicitly harmful to people in our community. It’s not enough that they don’t listen when you say something,” Gebru says. “Then they try to silence your scientific voice.”

In the aftermath, Alphabet CEO Sundar Pichai pledged an investigation; the results were not publicly released, but a leaked email recently revealed that the company plans to change its research publishing process, tie executive compensation to diversity numbers, and institute a more stringent process for “sensitive employee exits.”

In addition, the company appointed engineering VP Marian Croak to oversee the AI ethics team and report to Dean. A Black woman with little experience in responsible AI, Croak called for “more diplomatic” conversations within the field in her first statement in her new role.

But on the same day that the company wrapped up its investigation, it fired Margaret Mitchell, Gebru’s co-lead and the founder of Google’s ethical AI team. Mitchell had been using an algorithm to comb through her work communications, looking for evidence of discrimination against Gebru. In a statement to Fast Company, Google said that Mitchell had committed multiple violations of its code of conduct and security policies. (The company declined to comment further on this story.)

To many who work in AI ethics, Gebru’s sudden ouster and its continuing fallout have been a shock but not a surprise. It is a stark reminder of the extent to which Big Tech dominates their field. A handful of giant companies are able to use their money to direct the conversation around AI, determine which ideas get financial support, and decide who gets to be in the room to create and critique the technology.

At stake is the equitable development of a technology that already underpins many of our most important automated systems. From credit scoring and criminal sentencing to healthcare access and even whether you get a job interview or not, AI algorithms are making life-altering decisions with no oversight or transparency. The harms these models cause when deployed in the world are increasingly apparent: discriminatory hiring systems; racial profiling platforms targeting minority ethnic groups; racist predictive-policing dashboards. At least three Black men have been falsely arrested due to biased facial recognition technology.

For AI to work in the best interest of all members of society, the power dynamics across the industry must change. The people most likely to be harmed by algorithms—those in marginalized communities—need a say in AI’s development. “If the right people are not at the table, it’s not going to work,” Gebru says. “And in order for the right people to be at the table, they have to have power.”

A dominant force

Big Tech’s influence over AI ethics is near total. It begins with companies’ ability to lure top minds to industry research labs with prestige, computational resources and in-house data, and cold hard cash.

Many leading ethical-AI researchers are ensconced within Big Tech, at labs such as the one Gebru and Mitchell used to lead. Gebru herself came from Microsoft Research before landing at Google. And though Google has gutted the leadership of its AI ethics team, other tech giants continue building up their own versions. Microsoft, for one, now has a Chief Responsible AI officer and claims it is operationalizing its AI principles.

But as Gebru’s own experience demonstrates, it’s not clear that in-house AI ethics researchers have much say in what their employers are developing. Indeed, Reuters reported in December that Google has, in several instances, told researchers to “strike a positive tone” in their papers’ references to Google products. Large tech companies tend to be more focused on shipping products quickly and developing new algorithms to maintain their supremacy than on understanding the potential impacts of their AI. That’s why many experts believe that Big Tech’s investments in AI ethics are little more than PR. “This is bigger than just Timnit,” says Safiya Noble, professor at UCLA and the cofounder and codirector of the Center for Critical Internet Inquiry. “This is about an industry broadly that is predicated upon extraction and exploitation and that does everything it can to obfuscate that.”

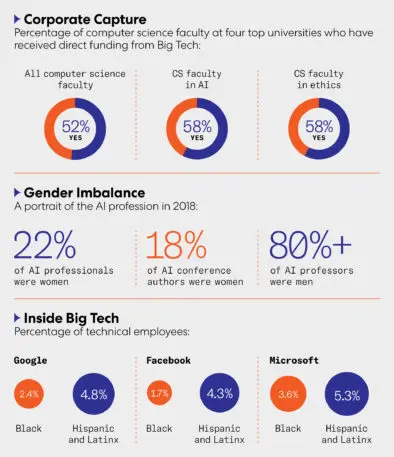

The industry’s power isn’t just potent within its own walls; that dominance extends throughout academia and the nonprofit world, to a chilling degree. A 2020 study found that at four top universities, more than half of AI ethics researchers whose funding sources are known have accepted money from a tech giant. One of the largest pools of money dedicated to AI ethics is a joint grant funded by the National Science Foundation and Amazon, presenting a classic conflict of interest. “Amazon has a lot to lose from some of the suggestions that are coming out of the ethics-in-AI community,” points out Rediet Abebe, an incoming computer science professor at UC Berkeley who cofounded the organization Black in AI with Gebru to provide support for Black researchers in an overwhelmingly white field. Perhaps unsurprisingly, 9 out of the 10 principal investigators in the first group to be awarded NSF-Amazon grant money are male, and all are white or Asian. (Amazon did not respond to a request for comment.)

“When [Big Tech’s] money is handed off to these other institutions, whether it’s large research-based universities or small and large nonprofits, it’s those in power dictating how that money gets spent, whose work and ideas get resources,” says Rashida Richardson, the former director of policy at AI ethics think thank AI Now and an incoming professor of law and political science at Northeastern Law School.

That sandbox often takes the form of conferences—one of the primary ways that researchers in this space come together to share their work and collaborate. Big Tech companies are a pervasive presence at these events, including the ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (FAccT), which Mitchell cochairs (Gebru was previously on the executive committee and remains involved with the conference). This year’s FAccT, which begins in March, is sponsored by Google, Facebook, IBM, and Microsoft, among others. And although the event forbids sponsors to influence content, most conferences don’t have such clear policies.

The most prestigious machine learning conference, NeurIPS, has had at least two Big Tech companies as primary sponsors since 2015, according to the same 2020 study that analyzed the influence of Big Tech money in universities. “When considering workshops [at NeurIPS] relating to ethics or fairness, all but one have at least one organizer who is affiliated or was recently affiliated with Big Tech,” write the paper’s authors, Mohamed Abdalla of the University of Toronto and Moustafa Abdalla of Harvard Medical School. “By controlling the agenda of such workshops, Big Tech controls the discussions, and can shift the types of questions being asked.”

One clear way that Big Tech steers the conversation: by supporting research that’s focused on engineered fixes to the problems of AI bias and fairness, rather than work that critically examines how AI models could exacerbate inequalities. Tech companies “throw their weight behind engineered solutions to what are social problems,” says Ali Alkhatib, a research fellow at the Center for Applied Data Ethics at the University of San Francisco.

Google’s main critique of Gebru’s peer-reviewed paper—and the company’s purported reason for asking her to retract it—was that she didn’t reference enough of the technical solutions to the challenges of AI bias and outsized carbon emissions that she and her coauthors explored. The paper, called “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?,” will be published at this year’s FAccT conference with the names of several coauthors who still work at Google removed.

Who’s in the room

When Deborah Raji was an engineering student at the University of Toronto in 2017, she attended her first machine learning research conference. One thing stood out to her: Of the roughly 8,000 attendees, less than 100 were Black. Fortunately, one of them was Gebru.

“I can say definitively I would not be in the field today if it wasn’t for [her organization] Black in AI,” Raji says. Since then, she has worked closely with Gebru and researcher-activist Joy Buolamwini, founder of the Algorithmic Justice League, on groundbreaking reports that found gender and racial bias in commercially available facial recognition technology. Today, Raji is a fellow at Mozilla focusing on AI accountability.

The field of AI ethics, like much of the rest of AI, has a serious diversity problem. While tech companies don’t release granular diversity numbers for their different units, Black employees are underrepresented across tech, and even more so in technical positions. Gebru has said she was the first Black woman to be hired as a research scientist at Google, and she and Mitchell had a reputation for building the most diverse team at Google Research. It’s not clear that the inclusion they fostered extends beyond the ethical AI team. This workplace homogeneity doesn’t just impact careers; it creates an environment where it becomes impossible to build technology that works for everyone.

Root causes: From how AI research is funded to who gets hired, the industry’s problems run deep

Meanwhile, a new analysis of 30 top organizations that work on responsible AI—including Stanford HAI, AI Now, Data & Society, and Partnership on AI—reveals that of the 94 people leading these institutions, only three are Black and 24 are women. “A lot of the discussions within the space are dominated by the big [nonprofit] institutions, the elites of the world,” says Mia Shah-Dand, a former Google community group manager turned entrepreneur and activist who did the analysis through her nonprofit, Women in AI Ethics. “A handful of white men wield significant influence over millions and potentially billions in AI Ethics funding in this non-profit ecosystem, which is eerily like the overall AI tech for-profit ecosystem,” Shah-Dand writes in her report.

Bender, Gebru, and others say it’s important to empower researchers who are focused on AI’s impacts on people, particularly marginalized groups. Even better, institutions should be funding researchers who are from these marginalized groups. It’s the only way to ensure that the technology is inclusive and safe for all members of society.

A growing movement

“If you’ve never had to be on public assistance, you don’t understand surveillance,” says Yeshimabeit Milner, the cofounder and executive director of the nonprofit Data 4 Black Lives, which examines how the data that undergirds AI systems is disproportionately wielded against marginalized communities. Facial recognition surveillance, for example, has been used in policing, public housing, and even certain schools.

Our Data Bodies, for example, has embedded community researchers in cities such as Charlotte, Detroit, and Los Angeles. “Across all three cities, [community members] felt like their data was being extracted from them, not for their benefit, but a lot of times for their detriment—that these systems were integrating with one another and targeting and tracking people,” says Tawana Petty, a Detroit-based activist who worked with the Our Data Bodies Project. She is now the national organizing director of Data 4 Black Lives.

These organizations have made some progress. Thanks to the work of the AJL and others, several prominent companies including IBM and Amazon either changed their facial recognition algorithms or issued moratoria on selling them to police in 2020, and bans on police use of facial recognition technology have been spreading across the country. The Stop LAPD Spying Coalition sued the LAPD for not releasing information about its predictive policing tactics and won a victory in 2019, when the department was forced to expose which individuals and neighborhoods had been targeted with the technology.

“This activist work is exactly what we need to do,” says Cathy O’Neil, data scientist and founder of the algorithmic auditing consultancy ORCAA. She credits activists with changing the conversation so that AI bias is “a human problem, rather than some kind of a technical glitch.”

It’s no coincidence that Black women are leading many of the most effective efforts. “I find that Black women as people have dealt with these stereotypes their entire lives and experienced products not working for them,” says Raji. “You’re so close to the danger that you feel incredibly motivated and eager to address the issue.”

Data 4 Black Lives is also bringing together activists and researchers to collaborate on addressing data-related problems; in Atlanta, that means teaching data science skills. “It doesn’t have to be complicated. It can be as simple as a 300-person survey,” Milner says. “It’s about using that information to paint a picture of what’s happening.”

Training more people on the basics of using data is part of Milner’s mission to ensure tech is built equitably—and to bring into the conversation more people who’ve experienced algorithmic harms. “If we’re going to build a new risk assessment algorithm, we should definitely have somebody [in the room] who actually knows what it’s like to move through the criminal legal system,” she says. “The people who are really the experts—in addition to amazing folks like Dr. Gebru—are people who don’t have PhDs and who will never step foot in MIT or Harvard.”

Rebalancing tech’s power

For many researchers and advocates, the ultimate goal isn’t to raise the alarm when AI goes wrong, but to prevent biased and discriminatory systems from being built and released into the world in the first place. Given Big Tech’s overwhelming power, some believe that regulation may be the only truly effective bulwark to halt the implementation of destructive AI systems. “Right now there’s really nothing that prevents any type of technology from being deployed in any scenario,” Gebru says.

The tide may be turning. The Democrat-controlled Congress will likely reconsider a new version of the Algorithmic Accountability Act, first introduced in 2019, which would force companies to analyze the impact of automated decision-making systems. The sponsors of that bill, including Senators Cory Booker and Ron Wyden and Congresswoman Yvette Clarke, sent a letter to Google CEO Sundar Pichai after Gebru was forced out, raising concerns about Google’s treatment of Gebru, highlighting the company’s influence in the research community, and questioning Google’s commitment to mitigating the harms of its AI.

Timnit GebruRight now there’s really nothing that prevents any type of technology from being deployed in any scenario.”

Clarke says that regulation can prevent inequalities from getting “hardened and baked into” AI decision-making tools, such as whether or not someone can rent an apartment. One critique of the original Algorithmic Accountability Act was that it didn’t have the teeth to truly prevent AI bias from harming people. Clarke says her goal is to beef up the enforcement powers of the FTC “so another generation doesn’t come into [using technology] with the bias already baked in.”

Antitrust lawsuits could help change the balance of power for small businesses as well. Last year, the House Judiciary Committee called out how Big Tech uses its monopolistic control of the data required to train sophisticated AI to suppress small companies. “We [shouldn’t] take the power of these companies as a given,” Milner says. “It’s about questioning that power and trying to find these creative policy solutions.”

Other proposals for regulation include starting an FDA-like entity to create standards for algorithms and address data privacy, and raising taxes on companies to fund more independent research. UCLA’s Noble believes that by not paying their fair share in taxes, tech companies have starved the government in California, so that public research universities such as her own simply do not have enough resources. “This is part of the [reason] why they’ve had a monopoly on the discourse about what their tech is doing,” she says. There’s some precedent for this: Our Data Bodies originally received funding as part of the 2009 settlement of a lawsuit against Facebook for its Beacon program, which shared people’s purchases and internet history on the platform.

“Regulation doesn’t come out of nowhere, though,” says Meredith Whittaker, a prominent voice for tech-worker organizing. Whittaker helped put together the 2018 Google Walkout and is the cofounder and director of AI Now. “I think we do need strong, organized social movements to push for the kind of regulation that would actually remediate these harms.”

Indeed, worker activism has been one of the few mechanisms to force change at tech companies, from Google walking away from its drone image analysis project Maven to ending the practice of forced arbitration in sexual harassment cases. Individuals within Big Tech firms can not only protest when their products are going to be used for ill, they can push to ensure diverse teams are building these products and auditing them for bias in the first place—and band together when ethicists such as Gebru and Mitchell face retaliation.

Alex HannaThe union is a strong counterweight, especially for AI workers who want to speak up.”

Seeta Gangadharan, the cofounder of Our Data Bodies and a professor at the London School of Economics and Political Science, goes one step further, proposing that tech workers need to be taught how to be whistleblowers. She envisions summer schools for computer science graduates that would arm them with the resources for going public. That way, workers are already trained to reveal inside knowledge of harmful technologies that their future employers may develop.

A month after Gebru was pushed out of Google, hundreds of workers at its parent company, Alphabet, announced that they were unionizing. For Alex Hanna, a senior researcher on Gebru and Mitchell’s former team at Google, the Alphabet Workers Union is a crucial step. “The union is a strong counterweight, especially for AI workers who want to speak up against some of the abuses companies are perpetuating through AI products,” she says. For Gebru, the union is one of the few hopes for change that she has. “There has to be a lot of pressure,” she says.

Hanna cautions that building up this countervailing force to combat Big Tech’s influence will take time. Others are less patient. “These companies have so much power,” says Shah-Dand. “Someone has to dismantle them, whether it’s inside or outside.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.