Travis Holoway, the CEO and cofounder of SoLo Funds, says his startup isn’t just a quick way to take out a small, short-term loan. It’s the start of something bigger.

The startup, which raised $10 million in a Series A funding round last week, offers an app in which users can loan money to one another. Borrowers usually grant a small “tip” to their lenders when paying the money back, and in turn build up a “SoLo Score” that helps them take out larger loans in the future.

While Holoway says SoLo’s immediate purpose is to provide quick access to emergency capital, he adds that the startup’s true goal is to create a virtuous cycle, in which borrowers work their way up the financial ladder and become lenders on the platform. Along the way, he hopes to introduce those users to new banking and investment opportunities that they otherwise might have missed.

“If we can have individuals come here, take loans when they need them, pay them back on time, get access to more traditional financial tools and resources, and ultimately come back as a lender and pay that forward, that is the best life cycle of a user on our platform,” he says.

But while the startup may deliver on its promises of upward financial mobility, the reality is nuanced. Apps such as SoLo Funds aren’t as predatory as high-priced payday loans, but they carry some of the same financial traps. And with SoLo in particular, its use of use of social data to score users’ trustworthiness raises concerns about bias.

How SoLo Funds works

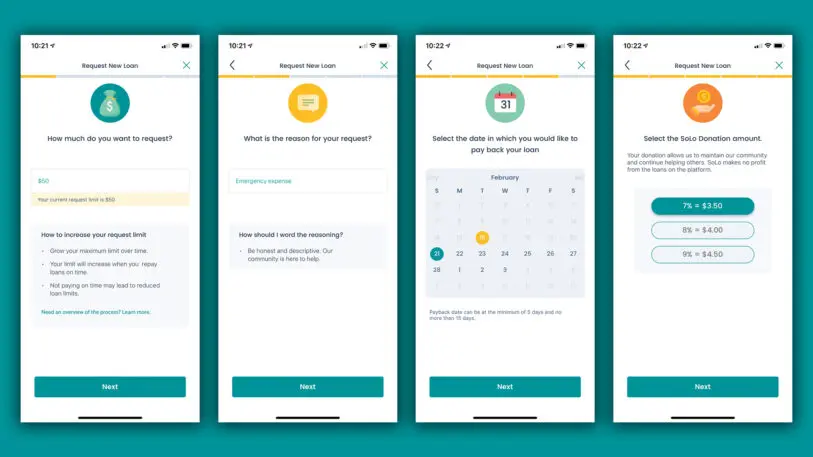

Compared to other small-dollar loan apps such as Earnin and Dave, SoLo Funds is unique in that it isn’t tied to employee paydays and doesn’t loan any money itself. Instead, it crowdsources the job, letting users request loans in an open marketplace. In exchange for taking on the risk, lenders can earn tips of up to 12% of the original loan value, with the exact amount being set by borrowers in advance.

Loans can be as small as $50 and can range up to $500, but SoLo doesn’t let new borrowers request whatever they want. To increase what they can borrow, users must develop a track record of successfully paying back loans on time. Doing so also contributes to a borrower’s SoLo Score, which lenders use to gauge the risk of any loan.

In a way, SoLo’s marketplace reflects the dynamics of real credit scores. Users with no history on the platform tend to pay higher tips of around 8% on average, but as their reputations improve, they’re able to attract lenders while offering less. Holoway says longtime borrowers tend to tip around 3% to 5%.

“It’s because they actually have more history on our platform over time, which makes lenders look at these individuals as safer opportunities,” he says.

As for borrowers who don’t pay back their loans on time, SoLo charges the borrower a one-time late fee of 15% plus a $5 administrative fee. Beyond that, however, the amount that borrowers owe doesn’t compound or increase over time.

That’s a major distinction from traditional payday lenders, whose business models revolve around trapping borrowers in a long-term cycle of debt. According to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the average borrower delays (or “rolls over”) a loan payment three to four times, and roughly a quarter of borrowers roll their loans over more than nine times. Each rollover allows lenders to collect more interest, and payday lenders make an estimated 75% of their fees from borrowers who’ve rolled over their loans more than 10 times in a year.

SoLo, by comparison, will refer delinquent borrowers to a collections agency and credit bureaus, but the other main penalty is not being able to use the platform anymore. Holoway says its default rate is three times better than the payday lending industry average. (Lenders can optionally defray the risk by paying for insurance as a fraction of their tip, though they also pay a fee if their loan is recovered through collections.)

“Borrowers are inclined to repay these loans because if they ever need access to this type of capital in the future, they will not have access to it if they are delinquent and don’t repay that initial loan,” he says.

Unmet needs

Holoway says the idea for SoLo Funds was borne from personal experience. He and cofounder Rodney Williams became best friends in the early aughts when they were both living in Cincinnati. Holoway later moved to New York and become a financial advisor, while Williams became a brand manager at Procter & Gamble and then cofounded the ultrasonic authentication service Lisnr.

We didn’t want to send anyone that we know, love, or care about to take one of those predatory loans.”

“We didn’t want to send anyone that we know, love, or care about to take one of those predatory loans, so at that point we realized there was an opportunity,” Holoway says.

He and Williams are both Black, and while Holoway doesn’t like to harp on the challenges they’ve faced as Black founders, he says they’ve had to be more resourceful about raising money. Data from Crunchbase shows that prior to SoLo’s series A, the startup raised money through convertible notes—a form of debt that turns into equity—in addition to a seed round and participation in Techstars, an accelerator based in Kansas City, Missouri.

Although some venture capitalists have questioned SoLo Funds’ ability to be successful in a downturn, Holoway points out that revenues have grown 40% month over month since the pandemic began, and the platform currently has 100,000 monthly active users.

“At the end of the day, the pattern matching that VCs do when they’re looking for their next billion-dollar exit, there’s not a number of people who look like me who have attained that,” he says. “When you put numbers on the board, people start to wake up.”

Hidden costs

That’s not to say SoLo Funds’ model is without potential downsides. Because the startup doesn’t collect any interest on loans, it has to rely on other ways of making money, some of which may come off as underhanded.

Industry watchdogs have also raised concerns about the tipping model. While SoLo’s tips are also voluntary, and about 7% of loans funded on the platform involve no tipping at all, the app notes that loans are much more likely to be funded when users tip the maximum amount. Between tips and donations, users may end up paying a rate that’s not much more favorable than payday loans, even if the model for late payments is less predatory.

“In general, the tip model is just evading the rules around lending fee disclosures, and people end up paying a lot of money, and it’s not clear how voluntary the tips are,” says Lauren Saunders, the associate director for the National Consumer Law Center.

The way SoLo Funds factors social media data into users’ reputation scores gets into murky territory as well. (Holoway wouldn’t tell me much about the details of how this works, saying that they’re proprietary.) Saunders says that because social media can be linked to a users’ race and community, using this data raises concerns over fair lending.

“Most lenders stay away from using social media out of fear of violating fair lending rules,” she says.

Holoway notes that SoLo Funds isn’t bound by those rules because it’s not a lender itself and doesn’t share any of its data with lenders on the platform. But in a way, users still see the effects of that data through the scores they’re shown for each borrower. And without reading SoLo’s terms of service, users may not even realize that data is being used for their scores in the first place.

“This is not an area that is well understood in terms of the actual fundamentals that determine whether someone has financial wherewithal or not, and there are all sorts of concerns about the ways that using those things as proxies embeds all sorts of other issues,” says Graham Steele, a senior fellow at the American Economic Liberties Project.

Whether those concerns invalidate what SoLo Funds is trying to accomplish is harder to say. Steele argues that short-term loans are at best a narrow solution for a small group of people, namely those who get into some kind of specific short-term pinch but otherwise can usually pay for what they need.

“For someone who is consistently behind on their rent, who is unemployed and has no prospective source of income, a loan is just going to be an anchor pulling them down, rather than a ladder which they can climb up,” Steele says.

But Holoway’s own personal experience says otherwise. Growing up in Cleveland during an economic downturn, he’s seen how frequently people can get into temporary jams. If SoLo can become the default place people turn to get out of those situations, it opens the door to all the company’s long-term plans, such as introducing users to banks, and credit cards, and better investment opportunities.

“Our goal,” he says, “is not for borrowers to remain borrowers on this platform forever.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.