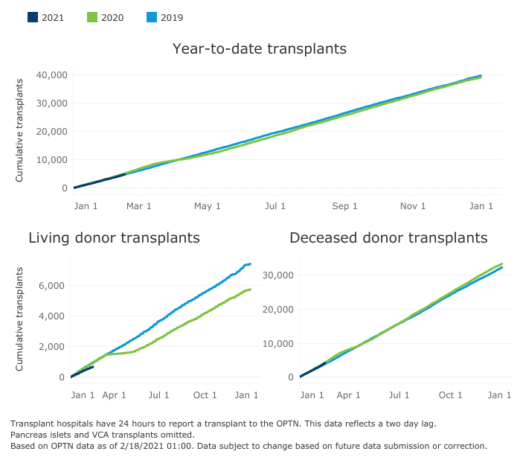

Organ transplants in the United States have been increasing over the last several years. In 2019, transplants from deceased donors rose by 10% while living donors increased by 7%. The growing system combines education, technological advances, various research, and public policy work to save lives off the 100,000-person waitlist. While kidneys are the top organ in transplant numbers, other key organs transplanted in America include the liver, heart, and lungs. The transplant community has been working together for years to increase organ donations for those in need.

Experts say that deceased donors alone will not resolve the waitlist. Organizations like the American Kidney Fund (AKF), among other things, work to get rid of kidney disease in the first place. They provide education and access to resources to help make it easier, and encourage living donors to save a life.

As a kidney donor myself, I can confirm that multiple organizations work hard to make organ donation a safe and rewarding experience. Despite the progress in recent years, more living donors are necessary. Especially now.

Beginning in late March of last year as the COVID-19 pandemic swept the U.S., the country’s transplant system came to a screeching halt. Deceased donor donations dropped by 50% and living donor donations dropped by 90%.

“The pandemic caught everybody off guard,” says Dr. David Klassen, chief medical officer at United Networks for Organ Sharing (UNOS). “Nobody really saw it coming. Transplant is really a collaborative process by nature.”

In order for a surgery to be successful it requires both the transplant center and the donor hospital to be fully operational and functional, along with the organ procurement team for deceased donor organs; potential recipients and donors also have to have access to healthcare. Not only did COVID-19 affect all these groups individually, but it only takes one of them with a problem to disrupt the entire system.

Waves of impact

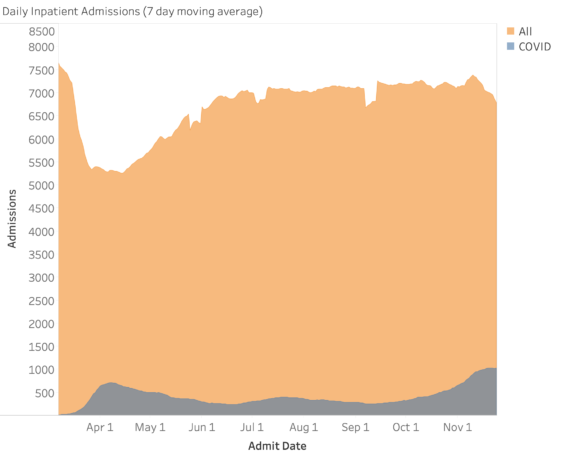

Once the pandemic hit, healthcare resources had to pivot. In many regions, beds, operating rooms, and healthcare workers were used mainly for treating COVID-19 patients. Cedars-Sinai in Los Angeles was just one transplant center that had to reallocate resources.

“Demand for resources and staffing and patient care had to be focused on the COVID-19 patients,” says Dr. Irene Kim, co-director of Cedars-Sinai Comprehensive Transplant Center. “Some of the transplant staff had to be redeployed and help care for COVID-19 . . . needs: testing for COVID-19, for example. Now, some of our nursing and MD staff are still administering vaccines.”

On top of resource reallocation, hospitals pulled back inpatient services because of safety questions. “We didn’t know about the virus, and we were just figuring out how to test donors,” says Kim. “We were learning so much as a medical community about the virus, not only in transplant but medicine in general. It wasn’t a safe environment to transplant. In L.A., 60% of deceased donors were testing positive for COVID-19. We can’t take those organs.”

Dialysis patients found themselves not only unable to put food on the table or pay their rent, but also unable to afford co-pays and premiums.

The transplant system and healthcare facilities were immediately and profoundly impacted by the pandemic. Individually, recipients and donors were hit just as hard, in different ways. The economic downturn rippled through people’s access to healthcare. Jobs were lost, which impacted insurance and access to treatment. Dialysis patients found themselves in the scary predicament of not only being unable to put food on the table or pay their rent, but also unable to afford their co-pays and premiums for life-saving treatment.

“The biggest impact we saw was financial,” says Mike Spigler, VP of patient services and kidney disease education at the American Kidney Fund. “In March we launched a coronavirus emergency fund, a financial assistance program offered to dialysis and recently transplanted patients. It was a small $250 grant and we seeded it with $300,000. Normally that amount would last a few months but we ran out of that money by 3 p.m. on day one. We were getting requests every 26 seconds. Our patients needed help paying bills, getting food on the table, and paying rent.” The AKF has provided financial assistance for more than 13,000 patients with $3.15 million.

“I have one patient who rents a couch out of an apartment for $200 a month,” Spigler adds. “He is undocumented, he is on dialysis, and he got laid off his job as a dishwasher. When he got a new job, he got sick and was diagnosed with COVID-19 the day before his first shift. He had no choice, he told his social worker he planned to go into work because he has to pay that rent or else he will be out on the street.” The AKF was able to provide that patient with a grant for that month so he could stay home and keep others from being exposed.

Pivoting to save lives

Changes in practice were required if the system was to continue transplantation after the pandemic’s initial disruption. Teams worked to get all donors tested for coronavirus so that those organs could be utilized and deceased donor transplants could continue. By late April, 100% of donors were being tested. UNOS instituted policies to unburden transplant centers from unnecessary administrative tasks associated with patient follow up. Telehealth took a very large role in post-operative patient care.

“The actual transplant is the easy part,” says Kim. “The hard part is all the post-operative recovery. Our typical model is to bring a kidney transplant patient back twice a week for physical exams and monitoring. Our typical liver recipient comes back every week after transplant and twice a week for labs. Are we really going to bring this immunosuppressed patient back to possible exposure multiple times a week?”

Video visits and telehealth systems were put into place in March and April, alongside the general rethinking of post-operative care.

Another shift in practice included changes to donor procurements. The teams that usually came to retrieve organs for transplant found that they weren’t always allowed in hospitals. There was more use of local staff to procure in order to keep with safety procedures and allow transplants to continue.

“When New York hospitals were filled with COVID-19, the transplant community collaborated to honor the gift of life and make sure people in other areas were able to use available organs,” says Anne Paschke, communications specialist at UNOS. “It was amazing how the transplant community came together and shared everything that they were learning so that other areas could learn.”

UNOS hosted webinars that connected experts around the world to share their experiences and research so that doctors and transplant centers could learn quicker than by their own experience alone. On March 23, during the first webinar, a heart transplant doctor in Italy spoke about treating COVID-19-infected transplant recipients; on December 3, a Duke University Medical Center doctor shared findings on administering the vaccine to transplant recipients.

“The level of collaboration was impressive,” says Klassen. “The pandemic obviously was a world-wide event and within the transplant world there’s been clearly successful international collaboration and a lot of the early clinical knowledge came from outside the U.S. It allowed us to recuperate faster and keep the system moving ahead.”

A very different transplant experience

Theresa Caldron, a registered nurse in Oklahoma and AKF Ambassador, was able to receive a life-saving transplant once the system was able to resume some surgeries. She received an organ others had declined because of COVID-19. “I was diagnosed with kidney failure, autoimmune disorder, and renal failure,” she says. “Back in 2009, we knew I needed a kidney transplant but I wasn’t put on the transplant list until 2017. They let us know for the time being they were doing it on a case-by-case situation, they were not doing live donor surgeries in Oklahoma because they outlawed elective surgeries. The person who was before me on the list turned it down . . . I may not have gotten this kidney if it wasn’t for the pandemic.”

Caldron and her family had a very different transplant experience than most. “My husband had to drop me off at the front doors of the hospital and pick me up there when I was discharged,” she says. “We weren’t allowed in-person visits.” After the surgery Caldron didn’t see her doctor for six months, as all clinical visits were pivoted to be virtual. Both she and her husband are nurses, so their medical background allowed them the ability to feel comfortable without in-person visits, although she says that staff encouraged her to call for any reason at any time.

The care that Caldron received while in the hospital was different as well: “I was on a floor that they use specifically for transplant and cancer patients. Oklahoma lagged in COVID-19 numbers, hitting at a different time than other areas, and the hospital was pretty empty. I was only one of around five patients on this floor, so I received amazing care.”

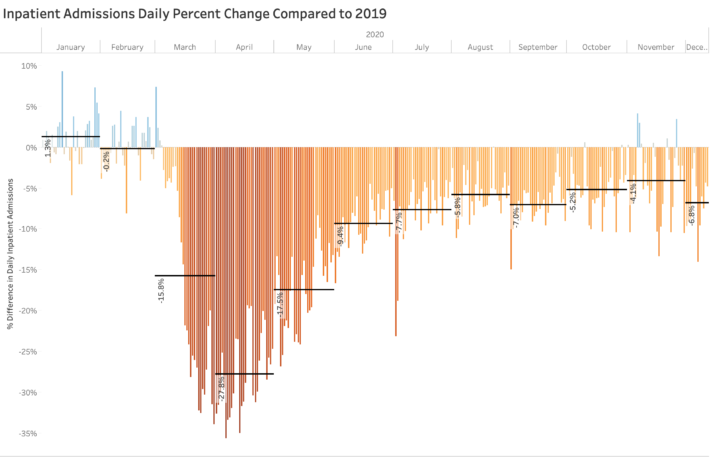

Hospitals fully prepped for large waves of COVID-19 infections that came at different times in different regions. Elective surgeries were postponed immediately; some came back in the following months. Many hospitals did not ultimately see an overflow of COVID-19 patients, although they put preventative safety procedures into place. “You had these hospitals that fully prepared for COVID-19 care, but the increase in COVID-19 inpatients did not make up for the decrease in elective surgeries and patients that deferred their care,” says Jennifer Ittner, senior director of data science at Strata Decision Technology.

“I think that the next three to five years are going to be hugely instrumental in how we understand how the coronavirus impacts transplant across the board: vaccination, donors, recipients,” says Cedars-Sinai’s Kim. “At this point in time we are still on that learning curve with transplants and coronavirus. From a month ago to a month from now, it’s constantly changing.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.