In the tech industry, a rigid internal system of job levels determines how much responsibility employees have and how much they get paid. But this system is often opaque, proprietary to each company, and hard to understand for workers, who can be left in the dark as to how their level is impacting their career path and their compensation.

That’s why a site called Levels.fyi uses crowdsourced data to create transparent leveling charts that track how levels at one company correspond to levels at another and how compensation within each company’s level varies. For its founders, the goal is to provide more transparency within the tech industry to help people understand where they stand currently, help them negotiate new job offers, and ultimately ensure that they’re being paid what they’re due—a historic problem within tech, particularly for women and people from underrepresented backgrounds.

“I think companies intentionally want to keep a lot of this information hidden and asymmetric. It’s obviously in their favor if they don’t disclose the full information to candidates,” says Zuhayeer Musa, one of Levels.fyi’s cofounders. “Our site is powerful because we help candidates [glean] this information so they can use it to negotiate and make sure they’re getting paid fairly.”

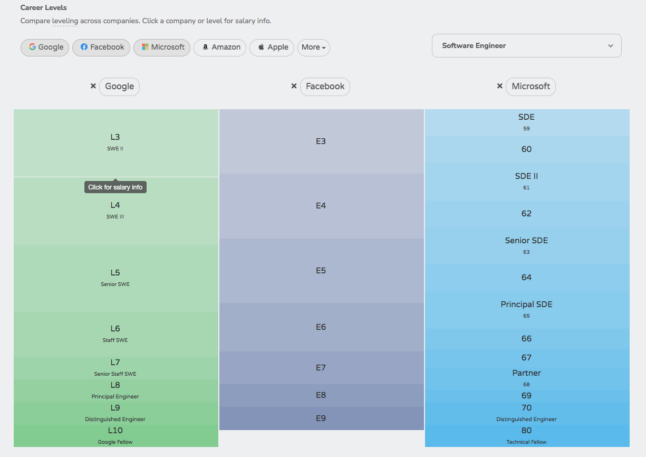

Levels.fyi got its start in 2017 when Musa and his cofounder, Zaheer Mohiuddin, were just starting to navigate entry-level tech jobs. Mohiuddin says they noticed that a lot of people had a similar question: How do you translate your level from one tech giant to another? For instance, what does a Google L3 software engineer translate to within Microsoft’s leveling system, which uses a numerical system starting at 59?

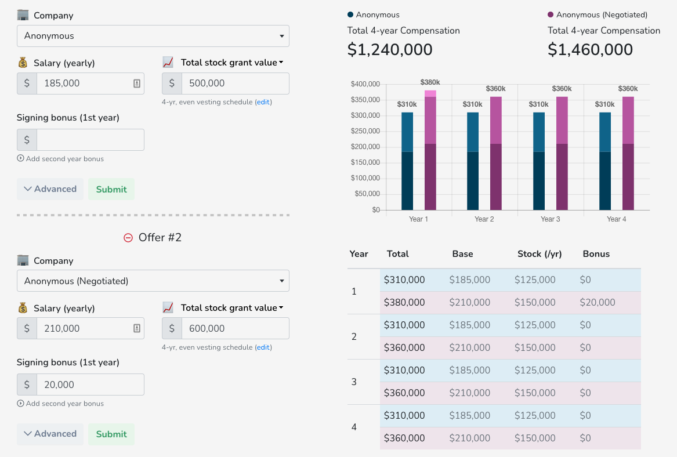

Levels.fyi was originally designed to show how these leveling systems stack up against each other. But the site has expanded to become a hub for transparent leveling and salary data for engineers at large tech firms, non-tech companies, and startups. It also includes resources on how to understand an entire compensation package, which at tech companies is usually a mix of base pay, stock options over a vesting schedule, and benefits. And most recently, Musa and Mohiuddin have started offering a negotiation service where current and former recruiters from companies such as Google, Amazon, and Salesforce provide one-on-one help for workers during the interview and negotiation process. So far, they say they’ve negotiated $31 million in salaries for tech workers.

Using verified, crowdsourced data to get paid

Beyond its focus on leveling, Levels.fyi is different from other crowdsourced data initiatives such as Glassdoor because a growing chunk of its data is verified, primarily through offer letters and W2 forms that people share privately to corroborate their publicly posted, anonymous compensation packages.

Mohiuddin says this verified data is “critical to solving pay disparity” because it provides authenticated points of comparison. “If people can point to the site and say, ‘This is verified information that I’m not being paid fairly,’ that’s something they can use in a conversation with recruiters and hiring managers,” he says.

The growing amount of verified data has also enabled Musa and Mohiuddin to begin selling anonymized bundles of this data back to some of the biggest tech companies, which have traditionally bought anonymized salary data from compensation data aggregators.

“Companies have been sharing salary data with each other for years,” Mohiuddin says. However, that doesn’t mean that Google and Microsoft are huddling together to compare how much they pay software engineers. Instead, tech companies submit all their salary information to a third-party company such as Radford, which then anonymizes data from a ream of similar employers and sells it back to them. “This is how compensation analysts decide what to pay people. They have the upper hand because they have verified salary information from these surveyors,” Mohiuddin says. “That doesn’t exist for engineers, for employees today.”

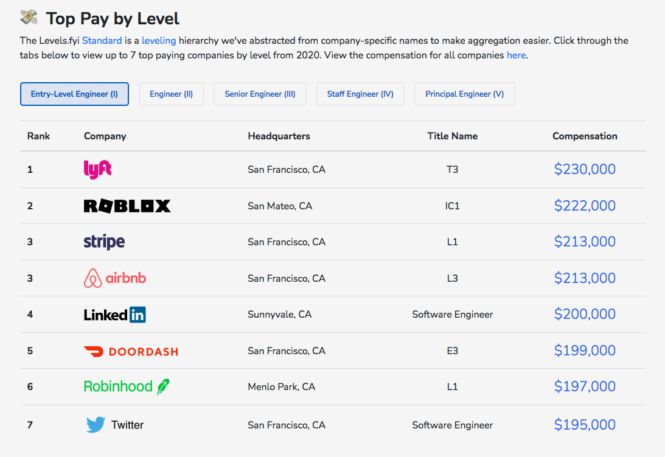

Levels.fyi has also started to analyze its database of verified salary information. At the end of 2020, the founders published a pay report that laid out the year’s top-paying companies by level and by location, as well as a gender pay gap report.

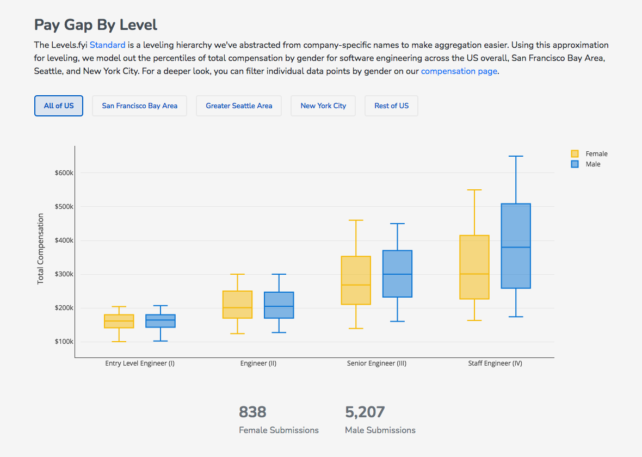

Although the data set they used for analysis is still small, with just over 6,000 data points, and there is undoubtedly selection bias in who decides to share their salary information, some trends have begun to emerge. Using a standardized leveling chart that they’ve developed to assess data across companies, the duo found that the median pay gap is very small at the entry level, when engineers are right out of college, but dramatically increases over time in a statistically significant way.

“As you go into higher levels where there’s more variance in compensation generally, we see the median gap increases between male and female engineers,” Musa says. “We see male engineers make significantly more in the staff engineer case—it almost goes up to $100,000 in median discrepancy. And what we’ve gotten out of this finding is that small differences in the beginning can eventually compound into larger differences later in your career.”

When leveling is discriminatory

This finding highlights another consistent issue in Silicon Valley: Companies hire women at a lower level than their male counterparts with the same experience, which compounds over time and leads to lower lifetime earnings.

The problem is part of multiple ongoing lawsuits, including class actions against Google and Oracle. It was also one of the factors in play for Pinterest whistleblowers Ifeoma Ozoma and Aerica Shimizu Banks, both of whom claim they were under-leveled for the work they were doing. When I spoke to Jim Finberg, the attorney representing female employees in both the Google and Oracle gender discrimination case, in summer 2020, he succinctly explained the issue with down-leveling: “The problem is you never catch up.”

Opaque leveling systems are part of this, since a role’s level isn’t always something that’s shared with you while you’re interviewing for a job. But this hidden information can have an outsize impact on the amount of compensation and stock options a new hire can receive. “It’s very important to make sure that the level you come in at is correct because your pay can be an order of magnitude off if it’s not,” Mohiuddin says.

According to Toni Locklear, an organizational psychologist who works with companies to create fair HR practices, bias can creep into the leveling during the interview process. She says she sees cases at high-tech companies where a job is posted without an associated level, and the company only makes a decision about a candidate’s future level toward the end of the interview process.

“I deal with this all the time,” she says. “What can happen is if the company doesn’t have really systematic job-related procedures and tools in palace, it opens the door for bias. It’s unintentional biases people have where they end up deciding even unconsciously that a woman or person of color should be leveled lower than the traditional engineering or tech employee.”

Negotiation in practice

Beyond the role of down-leveling in systemic discrimination, Musa and Mohiuddin say they’ve seen that it tends to be more prevalent at large tech companies compared to smaller ones and startups—and it’s one of the things they hope to help workers negotiate through their new service.

“Because you’re able to get away with it as a larger company, companies use their brand to hire people at lower levels,” Musa says. “Until recently I feel like people haven’t realized they were being down-leveled. It’s not something you can ID unless you have the data.”

If you can negotiate a higher level, the bracket of possible compensation increases significantly.”

That’s not possible for everyone, since some people’s skills and experience will clearly indicate which level is appropriate for them. But for those who are borderline, pushing a company to consider a higher level can result in much higher pay.

Levels.fyi’s negotiation service has been growing significantly, and has become the company’s largest revenue stream in just a few months. For an engineer, one negotiation session costs $249; three costs $537; and five sessions, which might be best suited for people juggling multiple offers, costs $845. The prices go up for manager- or leadership-level candidates because compensation gets more complex—in tech, those roles usually have far more financial upside through stock.

Once contracted, Levels.fyi’s negotiators help with drafting emails and call scripts, and even can provide mock negotiations (though they stop short of doing the negotiation on your behalf). They’ve shown signs of success so far—the founders say that some candidates who’ve used their service have increased their first-year compensation by $80,000 to $130,000.

And for Levels.fyi, seeing hundreds of pay packages and offer letters helps Musa and Mohiuddin provide better negotiation services to future tech workers; they’re constantly learning where the wiggle room for each company lies and how that can be leveraged to help get people more money.

Unfortunately, it’s still up to individuals to figure out if they’re not at the right level, both during the interview process and once they’re in a job. But with more transparency around salary and leveling data, Musa and Mohiuddin hope that more people will be empowered to make sure they’re being paid fairly and speak up if they’re not.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.