When a group of Redditors rallied together to buy up beleaguered GameStop and AMC stocks, they sent each company soaring against all market expectations. AMC in particular was able to wipe away $700 million in debt, rescuing the movie chain from certain bankruptcy. While many of the other gains may be short-lived, there’s no doubt history was made in a meme-fueled collective investment maneuver that will be studied and debated for years to come.

And at least some of the credit, or criticism, belongs to Robinhood, the free day-trading app that helped fuel the frenzy, soared to a top spot in the App Store, and launched a funding round toward a $30 billion valuation even as it became a villain to much of the internet for stopping trades on the two stocks that propelled the app to the top.

But Robinhood didn’t luck into this viral moment; Robinhood was designed to allow new users to impulse-buy. Robinhood’s interface is like no other trading app on the market. The app swaps poise, patience, and other hallmarks of careful investment for hyperbole, celebration, and immediate gratification. And the reason is simple: While other stock brokerage apps by industry mainstays such as Fidelity or Charles Schwab make money by taking a tiny sliver from your long-term investments, Robinhood makes the bulk of its revenue off stock transactions (an industry term called PFOF). So the more often you buy and sell stocks, the more money Robinhood makes—even if you lose money with each tap.

Robinhood’s entire experience is more about optimizing certain styles of engagement over proven techniques of investment.

“When I think about Robinhood, I like to compare it to social media apps. Twitter, Facebook, TikTok,” says Blain Reinkensmeyer, head of research at StockBrokers.com, who performs an annual audit of roughly a dozen popular stock trading apps.

As I deposit $1 into my Robinhood account to begin trading—opting to buy a tiny fraction of a single Tesla stock—Reinkensmeyer serves as my expert guide. He confirms, no, my eyes are not deceiving me. Robinhood is nudging me with investment peer pressure at every moment.

It’s feast or famine

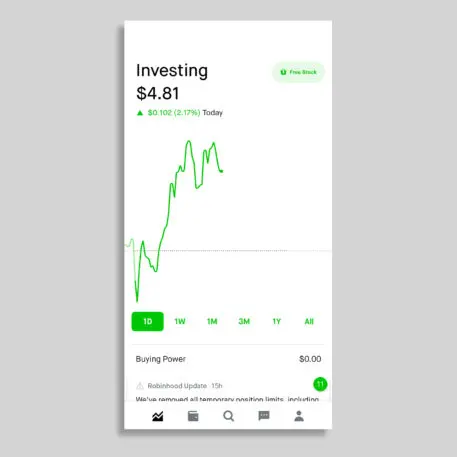

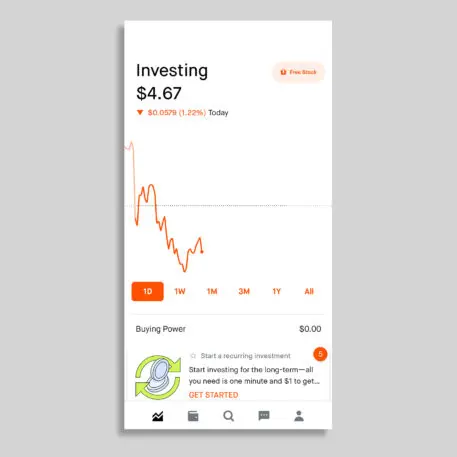

The very first screen you see when you log in to Robinhood is a big line graph that shows how your portfolio is performing, which updates automatically every five seconds. These sorts of investment dashboards aren’t unique to Robinhood. All apps have an account overview somewhere to track your portfolio. But Robinhood makes this experience particularly urgent, every time you load the app.

What’s even more interesting is what you see next, as you scroll down your home screen. You get news cards, offered up by the Robinhood algorithm, which consist of news that could impact company stock prices. After you experience the shock that your whole portfolio is sinking (by one cent), these news cards appear like a life raft. “Here, read all this news. Engage. Your next trade might rescue you.”

Only once you scroll past the news can you see your individual stocks. Here, again, resides a simple trick. Your stocks appear with their full share price (in red or green, based on if they’re up and down). What they don’t show is the PNL, or the actual profit or loss on your investment. In other words, while I own a $1 piece of an $800+ Tesla stock, Robinhood offers nothing there to convey the actual amount of my gain or loss as other apps will do (that’s only listed when I tap into the stock). Instead, the home page is feast or famine.

Training to engage

With your head in a frenzy over the magnitudes of your gains or losses, you may use this moment to go buy a new stock. But there’s a catch. It’s harder to do than you might think.

“Let’s say you’re logged in and want to place a trade. You can’t just tap trade like any other trading app. There are five buttons at the bottom, and there is no trade!” says Reinkensmeyer. “You have to click on the magnifying glass, which takes you to their Ideas page first. They are funneling you into the Ideas page, and you’ll see popular lists, news headlines, top movers, and an endless scroll of more news.”

If Robinhood’s goal is to sell you more stocks more often, why would it push you to so many trends and stories instead of just making it faster to buy a single stock? Reinkensmeyer believes it’s because Robinhood knows its audience—less experienced traders.

“It’s like Robinhood knows its customers on average have no clue what they want to buy,” says Reinkensmeyer. “So they list ideas to drive that behavior!”

A counterpoint to such criticism is that this news friction in the interface probably slows less experienced traders down, too. If you logged in to buy AMC, then saw stories that it was overvalued, you might question jumping on the trend. In this sense, Robinhood could be making a design decision here to benefit users even if it’s not directly serving its business plan.

In any case, this endless onslaught of news stories can also suck you into the drama of day trading. I had no intention of buying GameStop on its way down, but reading all these GameStop stories coming into my feed made it tough to ignore. I found myself wondering . . . maybe I should just buy a little to be part of the moment. In any case, this feed is meant to drive engagement, the chief metric of any social media app.

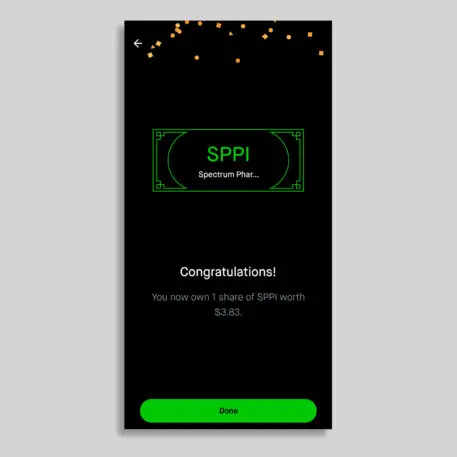

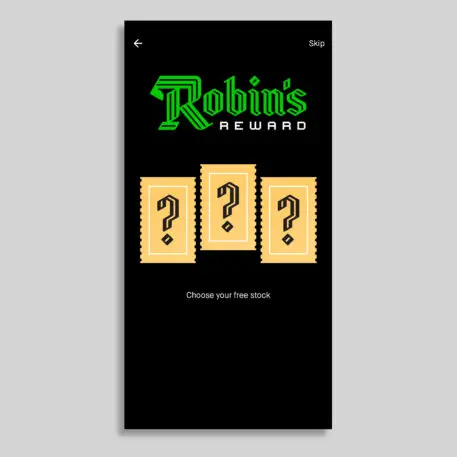

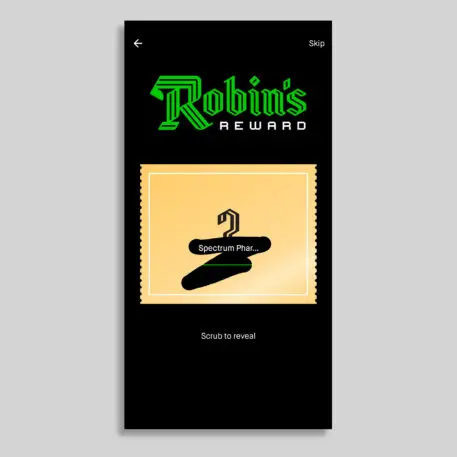

Gamifying trading to feel like a lottery

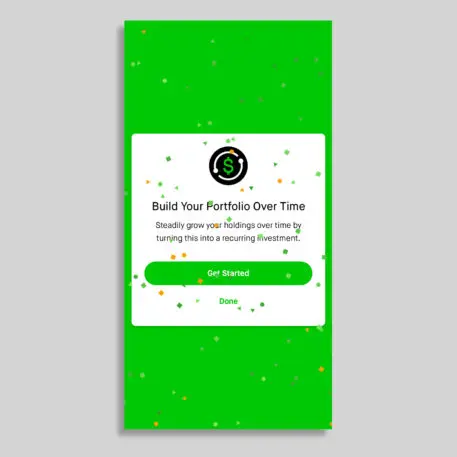

When I spent my $1 to buy a tiny fraction of Tesla stock, I knew that even if the stock sextupled in value, I’d never be able to buy more than a cup of coffee with my earnings. But Robinhood didn’t care. No no, this was a moment for celebration.

“When you go to sell, even for a profit, no confetti falls. Why, is there a regulatory reason?” muses Reinkensmeyer. “I don’t know, but it’s very apparent to me what behavior Robinhood wants to reinforce.”

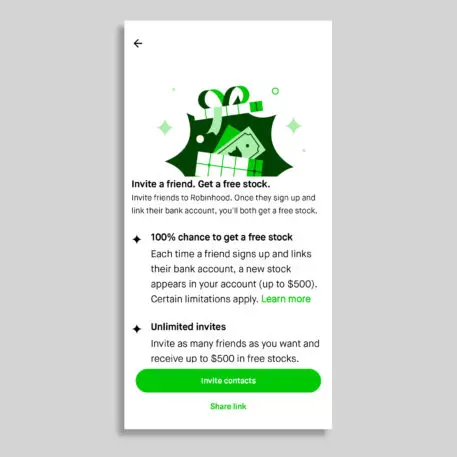

On the aforementioned home screen, a button reading “Free Stock” complete with a wrapped present permanently sits in the upper right-hand corner. It’s always there (and yes, it’s green when your stocks are up, and red when they’re down). Robinhood gives every user a free stock for joining the app.

It’s not all bad! But it’s not optimized for you to make money

Despite many of the UX games being played by Robinhood to ensure that it makes money, Reinkensmeyer doesn’t see it as some particularly evil force in trading. While he himself only has a few bucks in the app to test it, he admits to liking a few of the features quite a bit.

Reinkensmeyer argues there’s nothing inherently wrong about the “Free Stock” button. It’s just a free stock button! He also commends Robinhood’s newsletter as his favorite in the entire industry.

Ultimately, however, evidence suggests that Robinhood investors aren’t making out as well as the company is. Independent research by Oklahoma State and Emory University has found that, on average, Robinhood traders buy stocks that don’t perform any better over the next three to 20 days. “We find that Robinhood ownership changes are unrelated with future returns,” the researchers write, labeling Robinhood’s users as mere “noise traders” in the market. Yet, there may be a real value to Robinhood all the same. The app gives everyday investors an opportunity to experiment with trading—and for as little as $1—that is rarely as high-profile or volatile as the GameStop saga.

“Some people say Robinhood is just like a casino. I don’t believe that at all. I think investing in any way is healthy when it’s done [right],” concludes Reinkensmeyer. “Only speculate with 5% of the money you have. If you have $1,000 in cash, $50 to speculate is healthy.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.