Done right, artificial intelligence can be a valuable tool to help make the rollout of vaccines for COVID-19 more efficient, transparent, and fair. AI is particularly effective at balancing a wide range of competing goals and coming up with recommendations that are globally optimal. Using AI, you can optimally balance health factors, transmissibility risk, and economic impact considerations in order to prioritize who gets vaccinated and when.

But done wrong, AI can make the vaccine allocation process even more inefficient and divisive than it already is. The dangers of using poorly designed AI to guide vaccine allocation was dramatically demonstrated in December when Stanford Medicine relied on an algorithm to determine who should get vaccinated first.

In a story first reported by ProPublica, Stanford Medicine residents who worked in close contact with COVID-19 patients were left out of the first wave of health workers receiving the Pfizer vaccine. In their place were more established doctors who carried a lower risk of patient transmission than frontline residents being called on to intubate COVID-19 patients.

The culprit was an algorithm that Stanford used to select the first 5,000 medical workers to get vaccinated. The algorithm was designed to take into account factors such as age and the location or unit where the staff member worked in the hospital. But medical residents usually don’t have an assigned location, and they’re typically younger than established doctors, two factors that dropped them lower on the vaccination priority list. Only seven residents made the priority vaccination list, even though many of their peers were being asked to volunteer for ICU coverage in anticipation of a surge in COVID-19 cases.

Not only was the algorithm poorly designed, it also was a black box. Frontline healthcare workers who were put on a waiting list had no idea why. Stanford never informed its staff how the algorithm determined who would immediately get the vaccine and who would not. Stanford also did not communicate what would be the impact on its people—when could they expect to get a vaccine and how the delay might affect their chance of getting COVID-19.

The algorithm also failed to take in feedback from the frontlines, which would have immediately alerted officials to significant problems with the algorithm. Instead, residents were completely cut out of the process and felt betrayed by Stanford officials. Stanford administrators later apologized in an email to residents, saying, “Please know that the perceived lack of priority for residents and fellows was not the intent at all.”

Not the intent, perhaps, but built into the algorithm.

All too often, technologists focus on the accuracy of an AI system, but that leaves them with blind spots around its impact. The key here is impact, not accuracy. Stanford should have started with the expected impact on its people, built the AI to optimize that impact, and then clearly communicated the expected effect on each person. People don’t mind waiting as long as the process is fair and transparent.

Building a fair vaccine rollout with AI

For AI to be successful in managing who gets a vaccine, people have to see how the AI works and feel part of the process. The AI needs to explain its reasoning back to the people affected by the decisions when it balances what experts deem the three major factors in when someone should get a vaccine: health, transmissibility risk, and economic impact.

The first priority, of course, is health. What is your health outcome likely to be if you’re not vaccinated? An older person with high co-morbidities will rate very high because their life may depend on getting vaccinated.

The second major factor is transmissibility. How likely are you to be infected by the virus and spread it to others? A frontline healthcare worker, teacher, grocery store clerk, or a person in a long-term care facility rates high for transmissibility risk.

The third priority to balance is economic impact and quality of life. You want to prioritize people who aren’t able to work at all if they’re not vaccinated, such as a factory worker. People who can work remotely full time would be further down the priority list because their economic livelihoods don’t depend on getting a vaccine immediately.

Equity is built right in because a Latino grocery store worker who can’t work remotely, interacts with many people at work, and lives with a large family would naturally score high based on transmissibility and economic impact. This worker is not scoring high because of their ethnicity per se. They are scoring high because they legitimately have risk factors that are correlated with ethnicity.

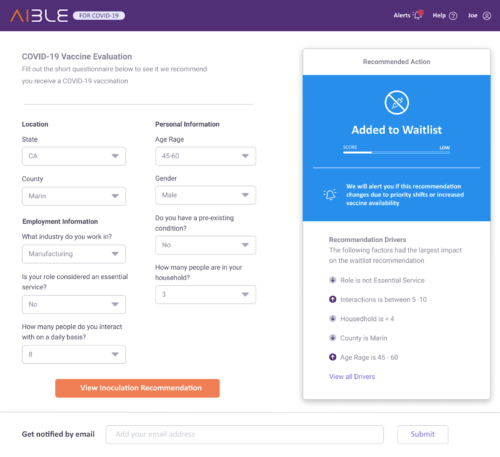

Here’s a screenshot of what an end-user might see when enrolled in an AI-powered vaccine evaluation process:

Once the AI has gathered information about a person’s age, location, employment, daily interactions, household size and pre-existing conditions, it either approves a vaccination or places the applicant on a waiting list.

People on the waitlist can view the recommendation drivers that had the largest impact on the decision and are alerted if the recommendation changes due to vaccine availability or other priority shifts. If the AI doesn’t explain to people exactly why they are on a waiting list, you’ll always have a large section of the population who feel they’re being treated unfairly.

We can’t fight the pandemic with spreadsheets. We need to take advantage of the best tools of the digital age. The right kind of AI can mean the difference between a fair and equitable vaccine rollout—or a chaotic and divisive one.

Arijit Sengupta is the founder and CEO of Aible.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.