When the pandemic hit earlier this year, Scott Budnick was concerned for more than just the health of himself and his family. The Hollywood producer turned social justice activist was worried about all the men and women in prison, whom he’s worked with over the years both on a personal and professional level.

“As you know, cases in prisons right now are awful,” Budnick said recently, Zooming in from his home in the San Fernando Valley, where he was sitting in his office, a black baseball cap pulled down over his forehead. “There are some prisons where a third of the prison—if there are 3,000 people incarcerated, 1,000 of them have COVID-19. It’s really bad. It’s a petri dish. So we’re doing everything we can to bring as much hope as possible.”

Until Budnick was forced to stay out of correctional facilities due to lockdown orders, he continued to make visits to them, and he and the rapper Common made content to air on prison TV’s. “They were about to take away visiting, so prisoners couldn’t see their families,” he said. “They had stopped church. So if your outlook was religious, you weren’t going. They stopped college, they stopped high school, they stopped self-help programs” inside prisons.

Budnick’s interest in criminal justice reform informed his trajectory after he left his job running Hangover director Todd Phillips’s company. He says his life had become about lunches and dinners where “every single conversation with everybody was about writers, director, movies and TV shows. I just wanted more meaning.”

Suddenly, gross-out comedies didn’t satisfy.

Inspired by the conversation he created the entertainment production and co-financing company One Community. The company’s first project was Just Mercy, the Michael B. Jordan film about activist attorney Bryan Stevenson’s fight to reverse the death penalty sentence of a Black man wrongly convicted of murdering a white woman in Alabama.

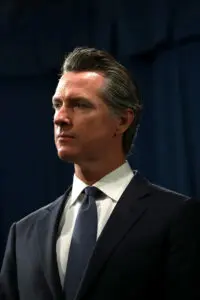

Released last January, Just Mercy was the test case for what One Community hopes to achieve; “an impact-first company,” as Budnick calls it. In other words, an entertainment company that starts with the awareness and change piece, using content to amplify it. The film, which also starred Jamie Foxx, made $50 million at the box office (it cost half that) when it was released by Warner Bros. But more important to Budnick than its financial return—though that matters, too—is that it raised awareness around criminal justice reform and led to actual government policy changes. After screening the film for California Governor Gavin Newsom and building a relationship with him, the legislature passed two bills easing restrictions on incarcerated individuals.

While Hollywood has produced plenty of films with uplifting themes in its time, their message tends to fade away minutes after opening weekend. Budnick’s goal is to create projects embedded in a campaign that can produce more lasting impact. It’s a mission that resonates more than ever, coming on the heels of a year rocked by COVID-19 and racial equity protests, and over the past several months a slew of heavy-hitters in the philanthropic world have joined Budnick’s cause. Among the company’s new investors are former Microsoft CEO and Clippers owner Steve Ballmer and his wife Connie; activist investor Daniel Loeb; Lowercase Capital‘s Chris and Crystal Sacca; Manchester by the Sea producer Kim Steward (the daughter of billionaire businessman David L. Steward); and Michael Rubin, founder and executive chairman of Fanatics, and partner in the Philadelphia 76ers. They join existing investors who include Endeavor Content; Milwaukee Bucks co-owner Wes Edens; Starwood Capital Group chairman and CEO Barry Sternlicht; Ford Foundation; and Mike Novogratz.

Armed with $60 million in funding, the plan now is to scale One Community to be able to produce between four and six film and TV projects a year. Next up is Respect, the Aretha Franklin biopic starring Jennifer Hudson that MGM is distributing next August. (The film was originally planned to come out in January but was pushed due to the pandemic.) Also on the way are In the Shadow of the Mountain, starring Selena Gomez as Peruvian mountaineer Silvia Vásquez-Lavado, the first openly gay woman to climb the highest mountain on every continent, and a survivor of sexual abuse; King Leopold’s Ghost, about imperialist oppression in the Congo in the early 20th century, which Ben Affleck is directing; and a film starring Margot Robbie about incarcerated women in California who fight fires while in prison but who are not allowed to become firefighters once they are released.

All the films will adhere to the Just Mercy model of tightly intertwining a long-lasting social justice campaign with the films and TV shows themselves. “It’s not just about running a campaign,” Budnick says. “We want to really figure out where a film and the empathy and inspiration that go along with it can impact something in a tangible, measurable way.”

“In five years,” says Kim Steward, “I believe that One Community will be a leader and driving force behind social change within the entertainment industry.”

Putting the campaign first

At One Community, a film’s social impact campaign is not conceived as part of the marketing of the movie once it’s largely complete. Rather it begins as soon as a project is in development, when the company’s chief impact officer Sonya Lockett—who spent 13 years at Viacom where she created BET Networks’ corporate social responsibility and public affairs agenda—works with the content team, “looking at projects, reading scripts.”

This is a very different approach than at most Hollywood production companies (even those that focus on social justice projects), where there is a more church-state divide between creatives and marketers and others involved in a film’s rollout and messaging. At the very least, people involved in a social impact campaign typically come on much later in the process to figure out strategy.

Lockett next creates a “braintrust” of experts in the field—nonprofit organizations, activists, foundation leaders—and brings them together for conversations to further hone the issues and help figure out the best, most impactful angles to pursue. It’s here where more layers are added to the discussion. For example, during one such meeting for Just Mercy, there was a conversation around how immigration is framed and “the narrative of what’s a good immigrant and what’s a not good immigrant,” Lockett says. “There was nuance in there that if you do not work on that issue day to day, you have no idea.”

“We’re not issue experts,” Budnick says bluntly. “One Community does not say, ‘This is how we’re going to help you.’ We’re going to come to [outside experts] and say, ‘We have this movie. We have an incredible, massive movie star in Selena Gomez. We have an exciting director. And here’s what the story is. How can we use whoever’s ultimately going to distribute that movie to move the needle on your issue? And we start building a campaign from there.”

For Just Mercy, after Lockett and her team designed the campaign, it was converted into a full-fledged organization, Represent Justice, which executed the outreach, tapping musicians and other celebrities, evangelical pastors, and NBA teams. With the NBA, One Community screened the film for them and then brought players into prison facilities for discussions with prisoners and to play hoops with them in a series called Play for Justice—to help spread the message and advocate for reform. Milwaukee Bucks guard George Hill, who partnered with Represent Justice, helped initiate the NBA work stoppage in August after the Kenosha shooting, and was able to broker a meeting with Wisconsin’s lieutenant governor and attorney general to advocate for reform.

Budnick says that going forward, One Community will oversee campaigns in-house just to keep things streamlined, but the idea that the campaign is essentially its own entity that lives and breathes indefinitely remains intact and, again, defies Hollywood protocol.

Measuring not just making reforms

Last September, Governor Newsom passed a bill that allowed people who have served as firefighters while doing time in prison to join the firefighting forces once they’re released. Budnick and his nonprofit, ARC, along with Represent Justice, had helped the governor’s team on the bill and were invited to the signing ceremony.

Budnick had hired him to become an ambassador for Just Mercy.

“After the movie, the governor and the first lady are incredibly emotional. I went up to him and said, ‘Governor, I’m glad you enjoyed the film. I’d love to use the film to help you in anything you want to do in criminal justice reform.’ I introduced Jarrett and told him his story, and the governor just broke down. They probably had a minute-long hug and the governor said, ‘Thank you for being here face to face to show me the effect I can have on people’s lives if we do this smartly.'”

“He looked at his team and told them to look for righteous people who were deserving of commutations. Three weeks later, he commuted his first people in his first year of office. Now he’s commuted up to 100 people and pardoned another 100 in his first two years of office, and we’ve worked together on multiple bills”—including the one related to incarcerated firefighters.

It’s this kind of measurable change that Budnick is shooting for at One Community.

Yes, projects need to be profitable. But more important is that real reform happens. The company has even set up a way to monitor its impact. With the help of Endeavor, Represent Justice created a “data dashboard” that investors can check to see “where we are at this point in the campaign metrics-wise,” Budnick says.

Reaching all hearts and minds

Budnick is keenly aware that social justice organizations run by wealthy people in Hollywood can all too easily be dismissed as yet another offshoot of woke capitalism. The same can be said of the people who invest in them, and he says he’s turned down billionaires who wanted to invest in One Community but “who did not have the right value system and were not willing to be humble and learn.”

Steve and Connie Ballmer were not that. After investing in ARC, the couple visited the organization “and sat in with about a dozen formerly incarcerated men and women, and boys and girls, and engaged in about a two-to-three-hour discussion with them that became so deep and emotional. They asked all the right questions.” The Ballmers then invited Budnick up to Seattle to screen Just Mercy for their foundation. After George Floyd’s killing last summer, he was invited to speak to 150 employees who work for the Clippers. “So it was just a very organic conversation,” Budnick said.

“When people are willing to reconsider tough issues from new perspectives, the possibility for real change is immense,” Steve Ballmer said. “Systemic racism is at the core of so many systems—not just our current criminal justice system, as Just Mercy illustrates, but also housing, education, health, and more—and this limits opportunity for communities of color. We applaud One Community for tackling these issues through entertainment and reaching broad audiences.”

Daniel Loeb, an activist investor who’s loudly rattled his saber at corporations like Disney and Sony over the years, is a more surprising new addition to the board given his conservative politics, but Budnick says that excites him. A bipartisan approach, after all, is crucial if Budnick wants to do more than just preach to the choir. On the Just Mercy campaign, for instance, Represent Justice reached out to the American Conservative Union and the National Association of Evangelicals to create events like a “faith call” with pastors to talk about the film and criminal justice reform. Foxx, Jordan, and Stevenson were all on the call. There was also a “Justice Sunday,” where pastors spoke about the film at the pulpit, and formerly incarcerated individuals were invited to join them.

Getting far-right conservatives on board with criminal justice reform is one thing. As Budnick points out, “A lot of Republicans don’t like big government and don’t like government waste. What’s more wasteful than a prison sentence that doesn’t rehabilitate people?”

But rallying conservatives will be more of an uphill battle for other projects, such as In the Shadow of the Mountain, which likely won’t be the subject of a group call amongst Evangelical pastors. Budnick says the issue is “definitely something I want to think through,” but adds, “I think people that are deeply rooted in faith would also be very deeply rooted in helping the young girls that Silvia (Vásquez-Lavado) helps and supporting her mission beyond her sexual orientation.” (Vásquez-Lavado runs an organization that helps victims of sexual abuse and trafficking help build inner strength and confidence through mountaineering.)

For now, Budnick is just happy that Just Mercy answered the question he posed to himself when he first started One Community. “Can a film with massive, global distribution by a studio get enough eyeballs, change enough hearts and minds, and lead to policy reform and philanthropic change?”

The answer, he knows, is yes.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.