If there’s one thing we know for certain about the future, it’s that we don’t know what will happen. But we can—and do—try to make predictions: about how climate change will affect our planet, what will happen to the economy, which jobs will be in demand and which ones will be obsolete.

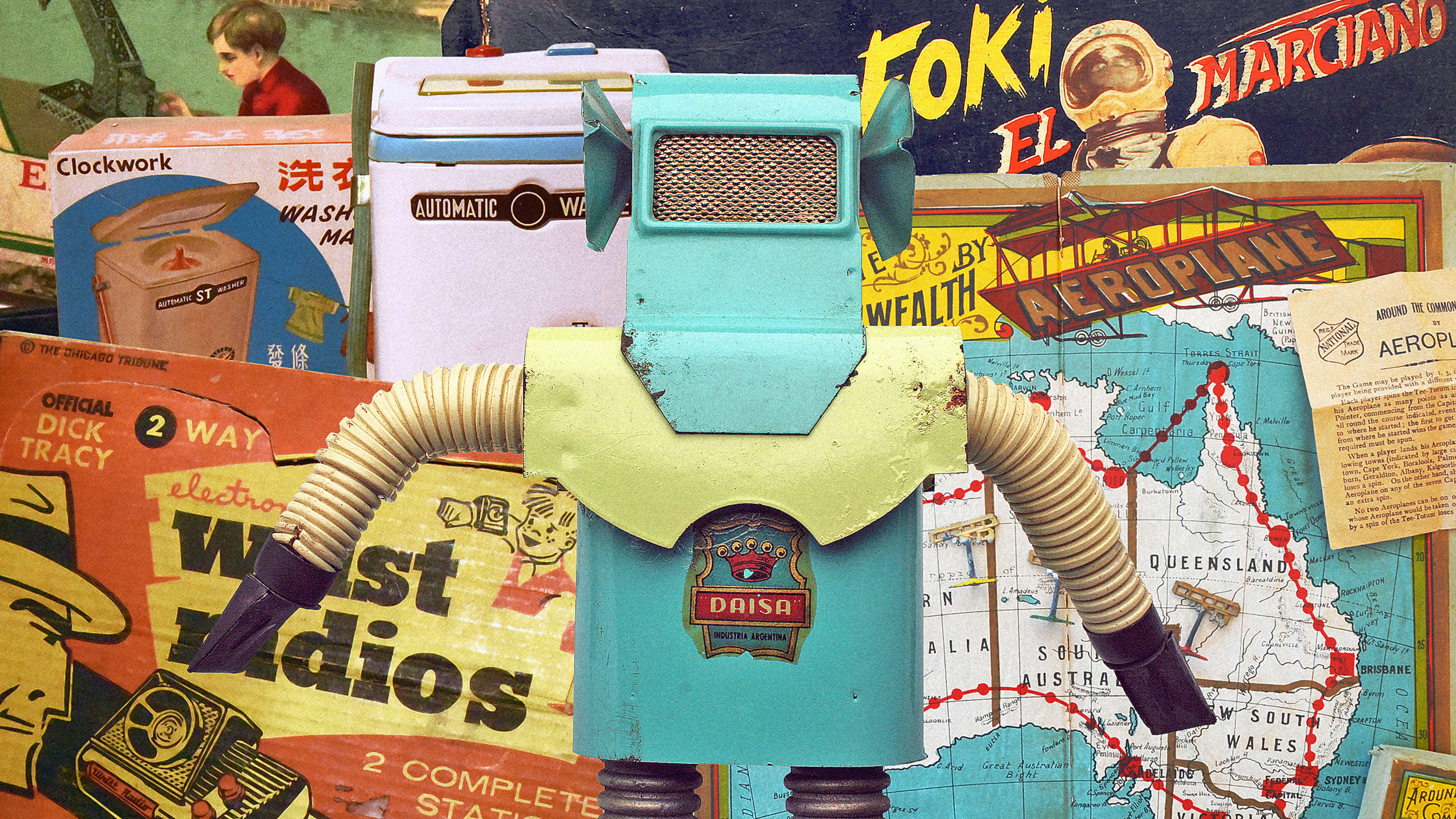

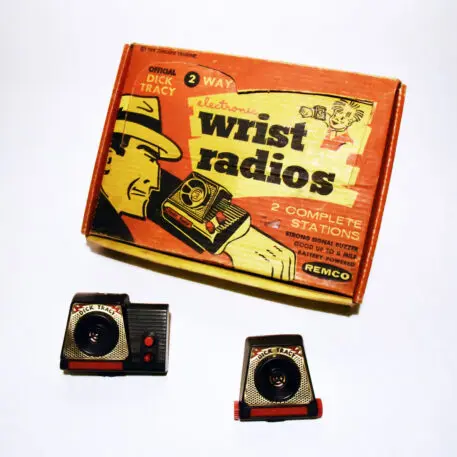

What if those predictions actually ended up affecting how the future unfolds, like self-fulfilling prophecies? It’s a question plaguing futurists, and now a project is trying to illustrate the problem by showing how things created in the past have colored the present. The simplest examples—items that truly shape the minds of our next generations—come in the form of children’s toys.

“What we needed was some way in which people could recognize the phenomenon in their own lives, and they could use that as a means by which to consider what sorts of predictions they make, what sort of impact those predictions might have going forward—individually as well as collectively in a society,” Keats explains. “Toys have a very direct way in which they influence the future through the children who play with them.”

It’s important, Keats says, for people to think about “what a future Meccano set might be that is not only one that involves girders and nuts and bolts, but also in which parts might grow organically.” That toy could be redesigned, for example, to consider how nature builds.

To illustrate the concept, Keats has redesigned the classic X-Ray Specs, which are an example, he says, of how toys can promote misleading possibilities that never come to fruition. Instead, Keats turned them into a “future viewer.” Rather than seeing the false illusion the original toy shows, the future viewer uses prisms to show multiple images “that suggest a multiplicity of futures,” Keats says. Similarly, a template you can download from the museum for a “biodegradable time capsule” is an exercise in creating a vision of the future but not clinging to it, instead letting that vision go as the paper time capsule disintegrates.

Toys are just the beginning. The Museum of Future History is partnering with the Museum of Tomorrow International, a global consortium of science museums, to continue the project. Keats envisions that eventually the Museum of Future History will have a physical location with traveling collections and an archive of books, newspaper clippings, fashion, computers, architecture—anything, basically, that can be examined for the way it may have “colonized the future.” The museum may even consult with designers or governments to create new objects that take all of this into consideration.

“One aspect of having a museum that puts objects like these on a pedestal is to engage people in that practice of close looking and careful consideration of the mechanism by which we make assumptions . . . and to find things by which better to question ourselves,” Keats says. “And to do so in a way not to shut us down, but rather to open us up.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.