Keep six feet of distance. Issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and adopted by many businesses, it’s the guideline that most of us have lived by during COVID-19.

But as the climate has turned cold and some of us have moved indoors, John Bush, a professor of applied mathematics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, calls such a rule of thumb “dangerous” and “overly simplistic.” Because when you’re inside, microscopic droplets are trapped right alongside you in a confined space, and standing six feet away from someone doesn’t stop the SARS-CoV-2 virus from floating in the air of your living room where you can potentially inhale it.

So are any of us safe indoors during the COVID-19 era? Can we go to a grocery store? Can we meet with a loved one? Bush, alongside his MIT colleague Martin Z. Bazant, have answered that question with a complex mathematical model, which simulates the fluid dynamics of virus-loaded respiratory droplets in any space, from a cozy kitchen to a gigantic concert hall.

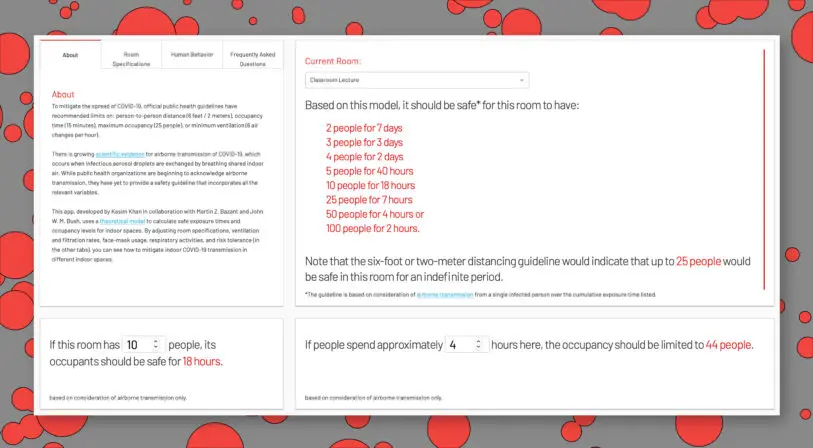

And because the equation is far too complicated for most people to understand, they turned their findings into a free online tool. Go to this website, and you can create your own custom scenario to judge COVID-19 risks for yourself.

At first glance, all of these controls might seem overwhelming. (And they are!) But the payoff is worth it. Because the tool gives you a very clear answer of how long how many people can safely be in a space together.

Let’s try an example. You just enjoyed Thanksgiving dinner in a typical 20-foot-by-20-foot dining room with a group of 10 people. People talked normally. Nobody was wearing masks since they were eating. The air was of average humidity.

“Based on this model, it should be safe for this room to have: 10 people for 18 minutes.” If you had simply followed a six-foot distance guideline and worn a mask, as the CDC suggests, these guests would be safe hanging out indefinitely. Which is clearly nonsensical.

“But what if they were wearing masks?” you ask. Good question. Let’s assume no one ate and instead talked through coarse cotton masks. Cotton masks bought them two more minutes of safety. Opening the windows to increase ventilation helps more. It buys another six minutes.

However, upgrading from coarse cotton masks to surgical masks increased the number to a whopping two hours. But with a catch: If those surgical masks are worn improperly by half of the people—say, the masks fit loosely or the wearers’ noses are sticking out—the safe time plummets back down to 32 minutes. Human factors matter a lot.

It’s a demonstration that wearing masks properly does help. After working on the source math behind this tool, Bush concludes that we absolutely should because it’s the most “dramatic” effect he noticed; it moves the needle in any circumstance, buying you precious minutes to stay safe. However, masks are not hazmat suits. They cannot overcome the reality of being in a small space with other people.

To prove the point, let’s make that dining room bigger. In fact, let’s stretch it into a 180,000-square-foot Walmart. And let’s fill it with 1,000 people who are good about wearing their coarse cotton masks. The only other variable I’m changing is that the air is probably a bit drier than in your home.

In these conditions, the tool says people should be safe for 68 minutes—if only one person has COVID-19.

As you can see, more space helps people stay safe. Just keep this in mind: Where I live, around Chicago, as many as 1 in 15 people currently have COVID-19, so as many as 66 people in that Walmart could have COVID-19 out of 1,000. Here, we run into a shortcoming of the tool. It models a single sick person in a space, not what happens when real infection rates hit what they are now. And there’s no way to tweak it accordingly.

Obviously this is just a model. It’s a simulation—researchers’ best guess of how our world works. It isn’t perfect and cannot guarantee your safety in any situation. But after using this MIT tool for more than an hour, I went from feeling comforted to feeling like things are even less safe than I thought. The model seems to suggest that, when we’re stuck indoors during the peak of a pandemic, the only way to “stay safe out there” is to try to not go out there—or let anyone in—at all.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.