Every year as summer approaches, there is a new wave of articles about “comfort wars”—between bosses and workers, men and women, Americans and Europeans, cold workouts and hot yoga. The New York Times covered the topic last year and concluded with a lesson from the University of California, Berkeley: “It appears that first world discomfort is a learned behavior.” But where is this behavior learned? Who decides what is comfortable?

Those same media reports often suggest that you and I aren’t deciding: It’s based on gender-biased comfort standards—outdated, ’60s-era studies of men in three-piece suits and fedoras sitting in an air-conditioned modernist laboratory who find 70°F perfectly comfortable during a sweltering Georgia summer. The reality is less nostalgic: Human comfort remains an area of active scientific research, and studies, old and new, are mostly performed with a balanced population of men and women.

This is one of a series of articles about how the concept of “indoors” affects our built environment. Read more:

• Mid-doors: The zone between inside and outside that could change building design

In fact, modern comfort standards generally prescribe a very large range of indoor conditions that are considered “comfortable.” One widely used standard, ASHRAE 55-2017, finds temperatures of 84°F (or even higher!) perfectly comfortable if a ceiling fan is provided for “elevated air speed.” The standards certainly have their gaps. They deal with an “average” person without identifying possible differences between men and women, and comfort during less-neutral activities such as exercise is not well-defined.

Our experience in our own practice confirms that this broad definition of thermal comfort can be perfectly acceptable. Staff surveys in both our own office and those of industry colleagues, such as architects KieranTimberlake, show that comfort complaints generally begin around combinations of temperature, humidity, and air speed. Decades of similar surveys by academic researchers confirm the same thing. The newly opened architecture school at the National University of Singapore was designed for 84°F, high humidity, and with ceiling fans, and has been praised as a comfortable place to study in an over-air-conditioned city known for two seasons: indoors and outdoors.

In fact, very few building operators—either on-the-ground building managers, supers, engineers, or their managers—even consider setting thermostats at temperatures required by these standards. Many aren’t even aware these standards exist. Why should they? Are they going to point to pages in a book when they respond to a call from an overheated or freezing-cold desk worker?

Instead, most building operators have one goal when it comes to comfort: minimize complaints. But even the standards say there is no ideal condition that results in zero complaints. Even the most comfortable combinations of temperature, humidity, and other conditions result in 5% of people dissatisfied—and up to 20% of people dissatisfied is often considered acceptable! Let’s pause here to commiserate with the building operator attempting to achieve the impossible task of satisfying everyone.

In some cases, comfort isn’t even the target and control is deliberately removed. Air conditioning is often perceived as a luxury, so retail spaces are overcooled to maintain this feeling. Turning off heat—or removing control of heat—is a common tactic for pushing tenants out of rent-stabilized housing.

So, who decides what is comfortable? The obvious answer: you. Me. All of us, according to our preference. But with that power comes a responsibility not to needlessly cool or heat our indoors in the era of climate crisis. Ignore what a thermostat on the wall says. Ignore what you’ve been taught is the “correct” temperature to be comfortable—since it’s far more than temperature that influences your comfort. Close your eyes, and listen to your internal thermostat. Are you comfortable?

If you aren’t comfortable, of course, the problem is that in a commercial building both you and the building operator can only work with the tools you’ve both been provided. That space heater hiding under your desk isn’t actually allowed, right? The thermostat on the wall is usually the only tool we’re given to adjust our comfort—if it’s not in a locked case.

Control of our environment is often removed because of a lack of trust. Design engineers and building operators fear that building occupants will make extreme adjustments and interfere with their carefully designed systems. Managers fear that coworkers in an open office will end up in a thermostat war. And we’ve lost the cultural understanding of all the ways we can take responsibility for our own comfort.

Of course, there is a precedent for taking control of our comfort: our own homes. There is much less research on comfort in homes than there is in commercial spaces, presumably because we adjust our homes to our preferences. Another example is our cars, where we are familiar with using many tools to adjust our comfort: not just temperature, but fan speed, heated seats, and simply putting down the window.

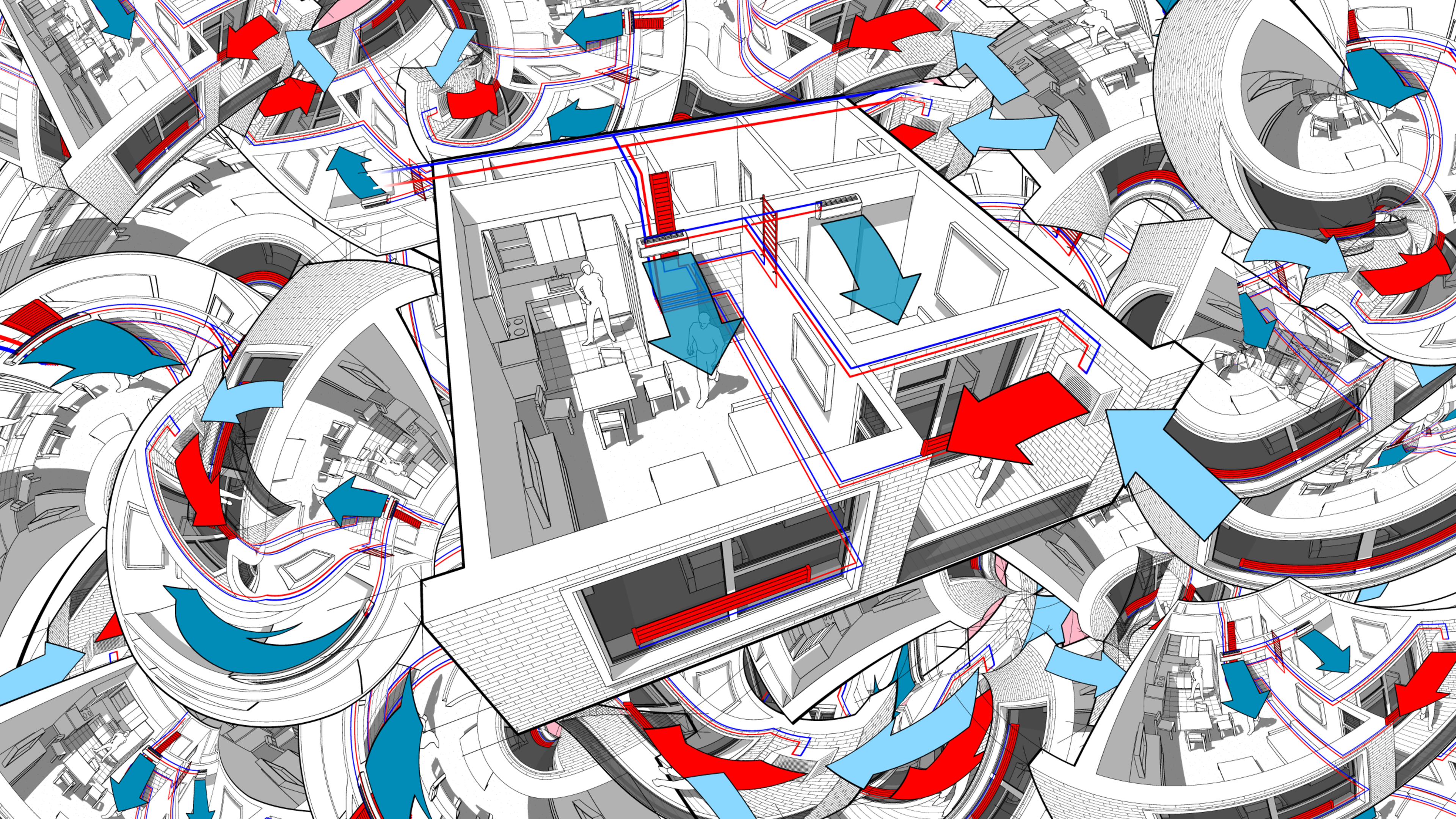

The solution to more comfortable commercial buildings, then, isn’t to fix the design standards or take away control but to give more control—but not just in the form of a thermostat. The simple ceiling fan is surging in popularity in low-energy commercial buildings exactly for this reason: They give occupants local control and allow comfort across a broader range of temperatures. Radiant heating and cooling (yes, cooling!) systems adjust the temperature of office surfaces rather than the air. Control doesn’t even have to be provided by the building. A wave of new research and devices aims to provide even more locally adjustable comfort, such as chairs with integrated heaters or fans and wearable devices like the Embr Wave. This isn’t a new idea. Heated tables, such as the Japanese kotatsu, have been used in other cultures for hundreds of years.

Rather than complaining about freezing-cold offices in the summer, advocate for more control over your environment. Ask for a ceiling fan. Don’t accept sealed, locked windows. Commercial building owners ultimately respond to what they think their occupants or tenants want, but there won’t be change in this conservative industry unless it is clear that occupants want this control. Given the right tools, shouldn’t a team that is expected to work together every day in a shared space be able to collectively find the best conditions for the space they share?

But in requesting control, consider your behavior as well. The minute you step into a room after walking briskly is probably not the best time to judge whether you are comfortable. Have thermal patience; give your body time to adapt to the environment, and then if your internal thermostat is still complaining, make your move.

Erik Olsen leads the New York team of climate engineering company Transsolar KlimaEngineering. He is passionate about human comfort and low-impact solutions for our environment. Transsolar is widely recognized as a world-leading innovator in the field of high-performance buildings. In partnership with top architects, their unique approach has led to numerous breakthrough projects around the globe.

Recognize your company's culture of innovation by applying to this year's Best Workplaces for Innovators Awards before the extended deadline, April 12.