Of all the ambitious feats a maker of computing devices can undertake, few are as tricky as switching processor architectures. It really is brain surgery, or at least its equivalent in digital form.

And even if moving to a new architecture offers clear advantages, much can go awry along the way. Consider Microsoft’s Surface Pro X laptop/tablet hybrid, which ditches the Intel processor in other Surface tablets—and most Windows computers, period—for a chip codesigned by Microsoft and Qualcomm. The Pro X is the sexiest, thinnest, and lightest Surface Pro to date, with the best battery life. Yet it can’t do something you might assume any Windows computer could do: run all Windows software. Among the high-profile products currently incompatible are Adobe’s Creative Cloud apps and the full version of Dropbox.

But this isn’t a review of the Surface Pro X. For the past few days, I’ve been using Apple’s new MacBook Air. Along with a new 13-inch MacBook Pro and Mac Mini, this update to the familiar wedge-shaped laptop is one of the first Macs to pack a processor designed by Apple itself, the M1. (Like the Surface Pro X’s Qualcomm chip, it incorporates technology from Arm.) These computers’ arrival marks the beginning of the end of the fifteen-year period in which Macs used Intel processors.

The epoch-shifting move from Intel to “Apple silicon” brings multiple benefits. Based on some of the same long-standing development work Apple has performed for its mobile processors, the M1 is fast and efficient, enabling the company to build Macs that offer both better performance and longer battery life. Like its mobile siblings, it has cores optimized for lighter tasks and ones engineered for heavy-duty processing—four of each, in this case. As it’s done for years with iPhones and iPads, Apple can also tightly integrate its hardware and software at the deepest possible level—for instance, by building chips optimized for the kind of AI that Apple needs for features in Big Sur, the new version of MacOS.

However, using this MacBook Air, I’ve been struck by the degree to which one principal design goal seems to have been: no surprises. Other than a few handy changes to the keyboard—for instance, the F6 key now toggles Do Not Disturb mode on and off—the new Air is a dead ringer for the old Intel-based Air. (Which, since Apple upgraded it just last March, is still the practically-new MacBook Air.)

In other words, this is a MacBook Air that looks, feels, and works like a MacBook Air–just a much faster, more power-efficient one. That’s possible in part because it’s capable of running existing applications that were written for Intel-based Macs and haven’t yet been updated for Apple silicon. In my experience, it runs them so well that making do while waiting for developers to rework apps for the M1 shouldn’t feel like a significant sacrifice for most people.

Apple has also kept the starting price the same-$999 for an Air with 8 GB of RAM and 256 GB of storage. That’s the version I tried, and while it’s a great basic machine, many folks might be best off investing an extra $25o for 512 GB of storage (and an additional core of graphics processing power). The highest-end configuration, fully tricked out with 16 GB of RAM and 2 TB of storage, goes for $2,049.

Apps, from M1 to Intel to iOS

For both Apple and its customers, the new M1-based Macs are the first step in a journey that will take a while. The company says that it expects two years to pass before its entire line of computers uses its own chips. How long it will take for third-party developers to create native software for the new architecture remains to be seen, but it’s safe to assume that some will do so swiftly, and others will lag. (For at least the next few years, what they’ll generally be creating are “universal” apps—single files that include all the code necessary to run natively on either an Intel or Apple chip.)

Apple has already updated its own apps, including both the ones that come preinstalled on Macs and additional offerings such as Final Cut Pro. Third-party developers also have M1-ready versions ready of Mac stalwarts such as OmniFocus, Pixelmator Pro, and Affinity Publisher. But virtually all Mac users will spend part of their time in non-native apps.

The new Macs run Intel apps using Rosetta 2, an emulator technology that converts Intel code into something that makes sense to the M1 chip. (Its name tips it hat to the original Rosetta, which performed a similar task in the early days of Intel Macs.)

The first time you run an app designed for Intel, Big Sur rejiggers it to run on the M1. That results in a pause that’s long enough that I sometimes thought I’d failed to properly double-click on an app’s icon. But once a piece of software goes through this process once, it just runs, with no glaring signs of performance degradation or other evidence of emulation. Or at least all the ones I tried did. They included my own Mac mainstays, such as Word, Photoshop, Chrome, Scrivener, Spotify, Mailplane, and 1Password. Utilities such as Moom and Ubar, which weave themselves deeply into the Mac interface, worked. So did my printer and two scanners.

I can’t say that my experience with the new MacBook Air has been utterly glitch-free. Photoshop crashed once, Webex spat out a couple of error messages I hadn’t seen before, and iMovie stopped working at one point until I rebooted. The Air’s screen also inexplicably blacked out once for about thirty seconds before returning to normal. That’s the sum of the problems I’ve experienced over 40+ hours of use. I’m not sure if any of them relate specifically to the M1 and Big Sur; even if some do, it’s not a terrible record for a platform that’s so radically new under the surface.

The move to Apple silicon may complicate virtualization, but it also opens up a new opportunity: M1-based Macs can run apps designed for iPhones and iPads. They appear in their own tab in search results in the Mac App Store; once installed, they live inside their own windows like true Mac apps, and you can control them using the keyboard and trackpad instead of touch.

Not everything will be available. Developers will be able to opt out of their apps showing up in the Mac App Store, and Apple will automatically remove ones dependent on features that Macs don’t have—such as the augmented-reality capabilities baked into iPhones and iPads. The theory is that hundreds of thousands of iOS and iPadOS apps and games will be left, including such biggies as Among Us.

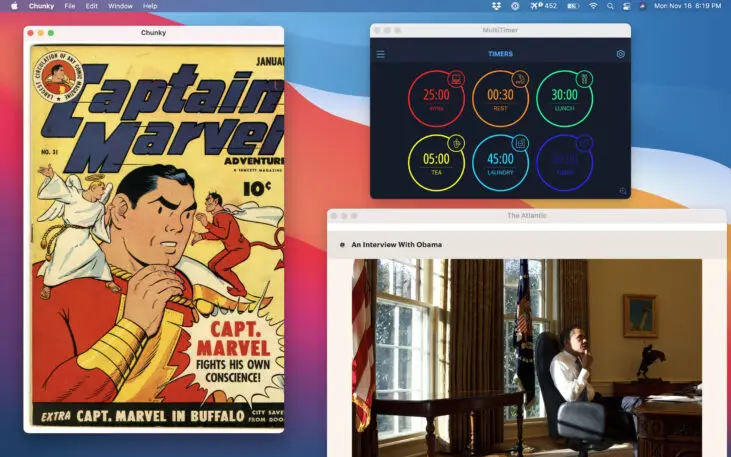

When I tried the new MacBook Air, the App Store was still indexing all those apps, so some might not have shown up in my searches. But most of the ones I hoped to install weren’t available, such as Instagram, Flipboard, and the New York Times app. Eventually, I did find a few of my iPad faves, including the MultiTimer timer app, Documents file manager, and Chunky comics reader. They ran, but having them available on a Mac felt like only a minor whoop at best.

In a way, the M1 MacBook Air’s iOS/iPadOS support not being more enticing is a compliment to the Mac ecosystem. If you want to do something, there are typically multiple native Mac apps that do it well. And they’ll feel more like they belong on a Mac than a repurposed mobile app ever will.

It keeps going and going

If one of the new MacBook Air’s major selling points is that it’s capable of handling exactly the same software that people are already using on previous Macs, what’s the incentive to spring for a new computer? For many people, it’s battery life. With its heritage in the technologies that give iPhones and iPads all-day endurance, the M1 processor is designed to keep going well after Intel chips would have conked out.

Apple says that the M1 MacBook Air delivers up to 15 hours of wireless web use and 18 hours of movie playback in the Apple TV app, vs. 11 hours of Web and 12 hours of Apple TV with the last Intel-based Air. Such stats tell you only so much about what you can expect. For one thing, you probably aren’t going to sit at your MacBook only browsing the web or only watching movies for hours on end. And even if you did, Apple’s use of “up to” is another way of saying you might get less.

The new Air snaps out of its slumber immediately, ready for work the moment you press its Touch ID sensor.

Those times suggest that I could take the new Air on the road and spend even an extra-demanding day using it without ever having to worry about finding a power plug. I’ve never been able to do that with any previous Mac I’ve used, which is one reason why I stopped traveling with a Mac and started toting an iPad.

A Mac, only faster

Another way the new MacBook Air has caught up with the iPad: As advertised, it snaps out of its slumber immediately, ready for work the moment you press its Touch ID sensor. (Intel Macs’ wake-up time ranges from snappy to glacial, based on factors I don’t fully understand.) Big Sur’s interface isn’t as freakishly instantaneous-feeling as an iPhone or iPad: toggle to a big app such as Photoshop or iMovie, and it may take a moment to pop into place. Still, I found the Air very responsive for a full-blown computer, and that was with 8 GB of RAM, the base amount.

Early third-party benchmarks have shown the new M1-equipped Macs trouncing even the most expensive Macs that use Intel chips. As you might expect, Apple’s own statements about performance gains compare M1 Macs to their immediate predecessors in technical terms: 3.5X faster CPU performance, 15X faster machine learning performance. The company also contrasts the M1 with the “latest PC laptop chip”-one from Intel, in case you couldn’t guess-and states that it delivers double the graphics performance using a third of the power.

Your experiences may vary depending on the work in question, and if you aren’t performing any particularly industrial-strength tasks, you might not have an urgent need for the M1’s horsepower. But judging from my experience, some people who might have felt obligated to bust their budget on a MacBook Pro in the past could find themselves entirely satisfied by the new MacBook Air’s performance.

The shape of MacBooks to come

The bottom line on the new MacBook Air is simple: Apple has succeeded in changing everything about its processor inside without tampering with any of the things people loved about the Air in the first place. That’s a feat. But it does mean that some obvious areas for technical and design upgrades remain—even if you buy into Apple’s mantra that Macs shouldn’t have touch screens.

Like previous MacBooks–all of which have a reputation for sporting outdated webcams–the new Air has a camera stuck at 720p resolution. Apple says that the M1 chip’s image signal processor wrings better quality out of the camera, and I found the improvement quite noticeable: Even in murky lighting, I looked more presentable. But 1080p resolution would be better still.

Your own to-do list may vary, but one way or another, Macs need to keep evolving. Having pulled off the MacBook Air’s processor transition so successfully, it would nice to think that Apple will take future models to all-new places. Maybe even ones where no Intel Mac could have gone.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.