For years, it seemed destined to remain the most bizarre and unfortunate presidential election any of us would see in our lifetimes.

On Election Day, November 7, 2000, the race between Vice President Al Gore, the Democratic nominee, and his Republican rival, Texas Governor George W. Bush, was too tight for anyone to be confident about the outcome. It became clear that Florida’s 29 electoral votes would determine the winner. Between that evening and the following morning, the TV networks declared in succession that Gore had won the state, that the outcome was uncertain, that Bush had won, and finally that it was too close to call.

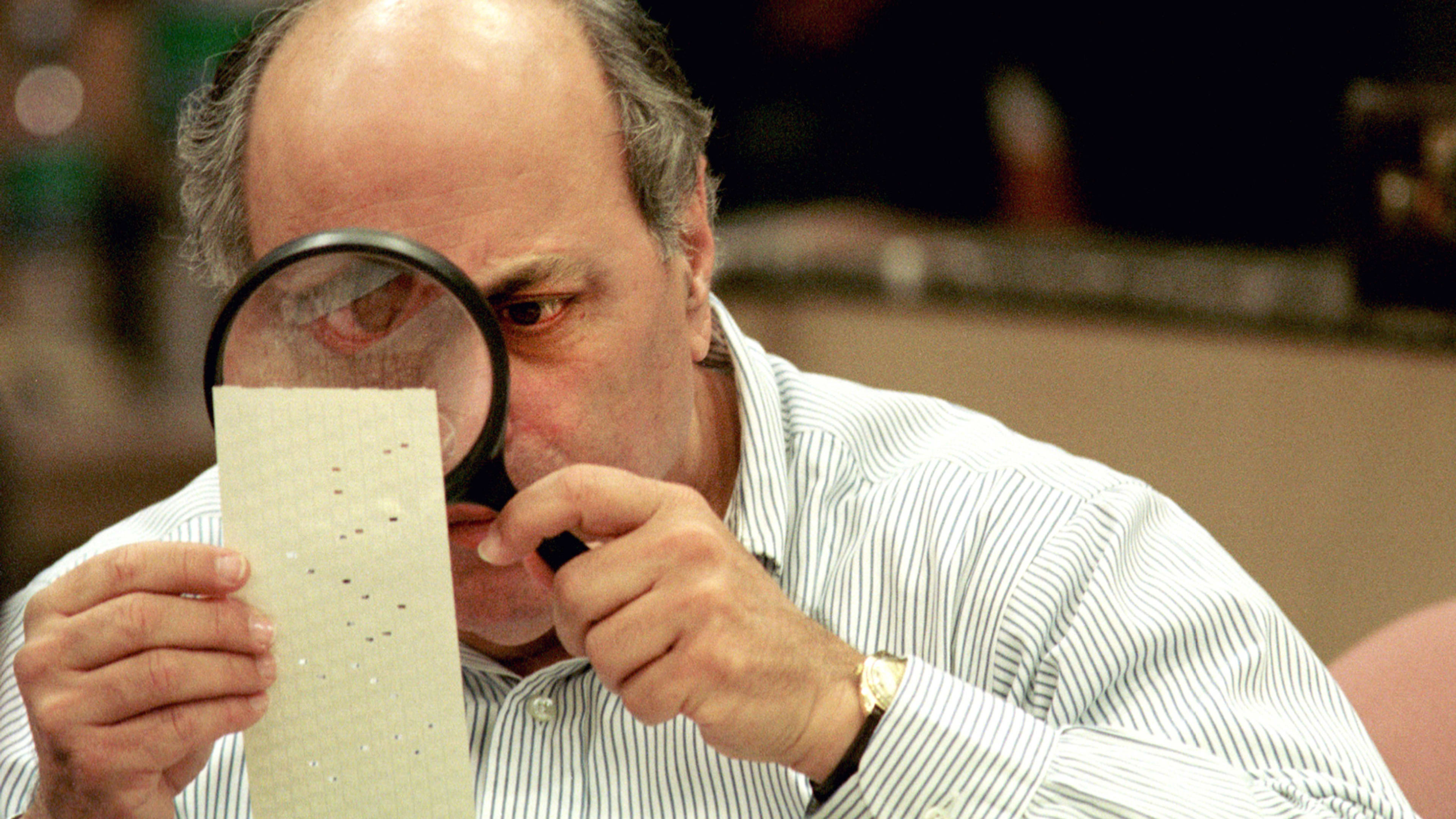

After an automatic machine recount left Bush with a lead of fewer than 1,000 votes, Gore sought a hand recount in four Florida counties. That led to a weeks-long effort that was part circus and part melodrama, with election officials attempting to divine the intentions of voters who had left their punch-card ballots with chads that were hanging, dimpled, or even pregnant. It all ended by a deeply controversial U.S. Supreme Court decision halting further counting. On December 13, Gore conceded—despite having won the popular vote—leaving Bush as the next president of the United States.

As many people have noted, the recount and court face-off eerily presage the possible upshot of the 2020 election if neither President Donald Trump or former Vice President Joe Biden is the clear-cut winner as of Election Day on Tuesday. You could write a book or make a movie about what happened in 2000 and the lessons we can draw from it. And multiple people have.

But when I decided to revisit the recount, I had a simpler question in mind: How did the internet cover it? No longer a medium in its infancy but not yet mature, the web was in a gangly teenager phase. From the vantage point of 2020’s online civic dystopia, the political-media web of 2000 is touching in its straightforwardness. Even so, it also reminds us that some of our current problems relating to talking about politics on the internet are hardly new.

Online evolution

The 2000 U.S. presidential election was only the third with a meaningful online element. In 1992, candidates staged town halls on proprietary online services such as CompuServe, GEnie, and an upstart called America Online. Four years later, they proved their tech savvy by launching their own home pages on the World Wide Web.

By 2000, the web was about a lot more than having a rudimentary home page. Which is not to say that it had fully arrived as a mainstay of American life. According to a Pew study, only 52% of American adults used the internet at all. The figure skewed heavily toward younger folks—just 14% of those 65 and over went online.

Still, the election 2000 sections of major news sites such as ABCNews.com, CNN.com, and NYTimes.com were pretty robust. They contained copious amounts of content (both repurposed from other media and original), interactive features like electoral-total counters, message boards, online chats with guests such as election-law specialists, and more. The journalists and web producers responsible for them couldn’t have expected it would take more than a month to come up with the next president. But at least they had a framework for their ongoing coverage of the Florida recount and associated court cases.

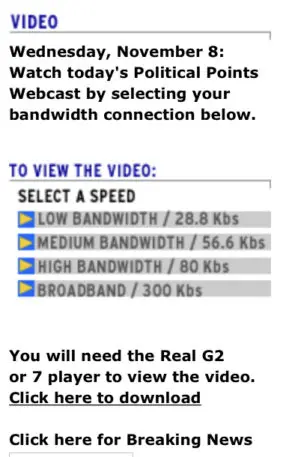

Browsing around the 20-year-old news pages—mostly via the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine—I was struck, above all, by how much streaming video and audio they featured, in a period before sufficient bandwidth for decent multimedia was a given. Home broadband had been rolling out for a while—I got my first cable modem in 1998–but even in 2000, a mere 1% of households had it. Everyone else who was on the net continued to plod along at dial-up speed, at least when at home. (At the time, it was common to have a speedier connection at the office, which made browsing the web at your desk an especially tempting distraction from . . . you know, work.)

Then there was the software required to stream. Within a couple of years, Macromedia’s popular Flash browser plug-in would add support for video, which made playing media in a browser as easy as pressing a button. Still later, HTML5 eliminated the need for a plug-in at all. But in 2000, consuming multimedia still demanded a lot of effort—especially given the quality of what you got in return.

When you landed on a webpage with video or audio, you often had to specify your media player—RealPlayer, Windows Media, or sometimes Apple’s QuickTime—and the speed of your internet connection. Rather than playing within the page, media spawned a stand-alone window. Video was tiny and grainy; audio had a tendency to sound like it was being broadcast from the ocean floor.

Even back then, the whole proposition struck some people as absurd. “Unless you’re stuck in sub-Saharan Africa, it’s hard to imagine why you wouldn’t watch the proceedings on TV,” analyst Jay Stanley told Cnet’s Patrick Ross and Patricia Jacobus. “Watching it on the Web is like using a laser to open a can of soup. It’s an unnecessary complication.”

Stanley was talking about the U.S. Supreme Court’s hearings on the recount. The fact that they were available in any form as part of news coverage was a bit of a landmark: In the past, the National Archives took up to a year to release audio of oral arguments, by which time they were history, not news. Noting the public’s urgent interest in the recount case, the Court swiftly made audio available to media outlets, which broadcast it on TV and streamed it over the web, sometimes with accompanying imagery and transcripts. (It took another decade until this speedy distribution became standard practice for all Supreme Court cases.)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VnC12JwOnlM

Along with court hearings, sites covered the election’s aftermath with streaming news reports—ones repurposed from TV, raw clips of moments such as Gore’s concession speech, and made-for-the-web programming such as a daily webcast coproduced by ABC News and The New York Times called Political Points. ABC News stalwart Sam Donaldson also hosted his own web show, giving credibility to the new medium.

As closely as I followed the recount as it was transpiring, the weird thing is that I have no recollection of consuming any of these multimedia elements. Mostly, my memories of online media in the pre-broadband days involve struggling to make it work at all, being annoyed by the results, and clicking off to do something else. But even if all I did was read the news from Florida in text form, there was plenty to keep me busy.

The public speaks

One fundamental difference between 2000 and 2020: Today, it’s far easier for anyone with an opinion on politics to chime in, whether by tweeting, Facebook posting, or uploading a video to YouTube. In 2000, online content about the recount was mostly generated by professionals employed by large media companies. Even the ability for readers to comment on articles was not yet a typical website feature.

However, many news sites featured message boards, similar to those that were a major attraction on services such as AOL. One such site was TIME.com, the newsweekly’s online presence. Its politics board, which naturally gravitated to discussion of the recount, greeted visitors with a welcome message that was actually anything but welcoming:

Since partisanship is the lifeblood of politics, we might not be able to discuss the election without it.

But we damned well can discuss it without the boneheaded meanness and stupidity that partisanship seems to have engendered this cycle.

A few other more extreme partisans, left and right, have been engaging in one of the most childish displays of name-calling and invective I’ve seen in a while.

That doesn’t include the blatant racist and/or homophobic rants and flame baiting that has led to the departure of a few folks who will no longer be welcome.

I urge all of you to stop it. Stop it now. It’s gone far beyond that ‘lively give-or-take’ we all engage in. It’s now just stupid.

And while we’re on the subject, cool it with the duplicate threads. Enough is enough.

Dave McLemore/TIME Online

(I’m trying to envision Mark Zuckerberg or Jack Dorsey describing their communities as places of “boneheaded meanness and stupidity” and instructing members to “Stop it now,” and my head is about to explode.)

The Wayback Machine does not seem to have preserved the actual text of messages on TIME’s boards. But even the subject lines on the Politics index page indicate that the discourse was not exactly elevated:

“Bush won the election……..Deal with it”

“HAIL TO HIS FRAUDULENCY!!!!”

“Worst Nightmare: GeeDubya as Prez and Senator Hillary”

“BUSH IS A THIEF!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!”

“It is SAD when we affirm cheating as a WAY to win, You have not won you’ve STOLEN a win, You have not Won!”

The TIME boards’ s tenor was not out of whack with other online forums of the time, such as usenet newsgroups. Groups such as alt.politics.democrats and alt.politics.republican were dominated by idealogues bellowing into echo chambers, sometimes in ALL CAPS to strengthen their case.

Here’s a usenet denizen named Eric W.—and though I can’t quite tell if he’s sincere or a troll, it doesn’t really matter:

GET OVER IT.WE WON.WE ARE THE MAJORITY NOW,SO KISS MY PARTISAN ASS!WE NOW HAVE FOUR,COUNT THEM, FOUR YEARS TO KICK ALL YOU STUPID DEMONCRATIC SOCIALISTS OUT OF HERE AND TURN THE WHITE HOUSE AND THIS COUNTRY BACK INTO A PLACE OF HONOR AGAIN.PICK A BETTER COUNTRY YOU BUNCH OF WHINERS AND GO THERE!

GOD BLESS AMERICA,RONALD REAGAN AND THE NRA.

(P.S.GOOD RIDDANCE TO THE LYING,CHEATING, FORNICATING BASTARD WE ALL KNOW AND HATE AS SLICK WILLY.)

Eric W.

In a way, reading such screeds is comforting: The state of online debate in 2020 may be terrible, but it’s not like it was ever otherwise. Then again, the 2000 internet hadn’t yet been contaminated by algorithmic feeds and organized attempts to spread disinformation. And did I mention that none of this stuff was being posted by the president of the United States?

Bloggers enter the fray

If there was a bright spot in social commentary on the Florida recount, it was the emergence of blogs as a medium for quick-hit analysis and curation of worthwhile reads around the web. Not yet a phenomenon—as they would become when the events of September 11, 2001, and their aftermath led to a flurry of “warblogging”—blogs had been quietly evolving for a few years. (Justin Hall, often cited as the first blogger, began posting in 1994.)

Technologist Dave Winer was both an early blogger and the creator of some of the first blogging tools used by other people. He’s also one of the few web publishers who has ensured that material he posted 20 years ago is still available, making it easy to see what his Scripting News had to say on the day after the 2000 election:

Last night’s story: First the networks said Gore won Florida, then Pennsylvania and Michigan — the key “battleground” states. Bush said no way, Florida is too close. They took it back. Later they called it for Bush. By that time it was the margin, the candidate who would win Florida would win the presidency. Gore calls Bush to concede. A Florida vote counter calls Gore while he’s on his way to give his concession speech. “Wait a minute Al, it’s not over yet.” Gore calls Bush and says “Dubya, I changed my mind.” Less than 2,000 votes separate the two in Florida. We await a recount. What a mess!

How did the networks all get it wrong in Florida twice? Just listened to PBS’s News Hour; they interviewed Warren Mitofsky, the statistician who advised CNN and CBS on their projections last night. The networks pool a lot of resources. We have so much faith in their projections. It seems safe to assume that in the future we won’t believe these reports so readily, and let’s look to the networks to separate their processes. What will the statisticians learn from the experience of making two mistakes in one race? Could it possibly have been more confusing? It’s Y2K, and Murphy is having a blast.

Here’s Josh Marshall, whose Talking Points Memo launched the week after Election Day. It was to become a major news and opinion site, but at first Marshall was a lone blogger who talked about himself in the third person:

As of about 7 PM on Tuesday, Talking Points heard (from his sources on CNN and MSNBC) that Palm Beach County had given Gore a measly 3 more votes, with about 1/5 of the precincts reporting. Broward had given the veep a semi-respectable 118 votes more with all the precincts reporting. And Miami-Dade had given Gore 114 more votes with 99 out of 614 precincts.

Let’s hear it for Miami-Dade! These guys are really pulling their weight!

(Actually the vote woman on MSNBC says those hundred-odd precincts already reporting lean even more Democratic than the rest of the county. So maybe it’s not as good as it sounds.)

Of course, the real issue is dimples. And which counties have how many ‘undervotes’ – that undiscovered country of hidden suffrage? Palm Beach has about 10,000; Broward’s got between 1,000 and 2,000; and Miami-Dade has some 10,750.

So, hey, there’s plenty of work to be done, assuming the Florida Supreme Court doesn’t completely shut Gore down.

Oh yeah, one other thing. If you include the already counted Palm Beach ballots with dimples Gore picks up another 301 votes.

So Gore’s not doing that badly. But obviously it’s going to come down to whether or not he gets his dimples.

Like Winer’s Scripting News and Marshall’s Talking Points Memo, Mickey Kaus’s Kausfiles is still with us, albeit as a bloggy Substack newsletter rather than a pure blog. Here he is on December 12, 2000:

Does Gore have the votes in Dade? Michael Barone’s projection says that if you conducted a full hand recount, on a par with the partial recount that was abandoned, Bush would gain 304 votes. The University of Wisconsin’s Bruce Hansen, in a widely-cited analysis, says Gore can be “expected to gain 254 votes.” Neither is close to the projection of 600 Gore votes the Democrats’ lawyers are citing in an attempt to show that a hand count would overcome Bush’s lead. The Gore projection is clearly bogus — the precincts counted in the partial hand count were heavily Democratic, and there is no reason to think Gore will pick up votes at the same rate in the remaining precincts, which were pro-Bush. The interesting question is how could Barone and Hansen come up with such different numbers. The answer seems to be this:

Barone looked at how many votes each candidate gained in the aborted hand-count, whatever the reason, and compared that with the votes they’d already obtained in those precincts. Though these were pro-Gore areas, Bush actually picked up more new votes relative to his old votes. Barone then projected this new vote/old vote ratio out for the rest of the precincts.

Hansen’s more technically-sophisticated projection was based on a model that basically assumed that undervotes were the only source of error. He looked at the number of undervotes in each precinct, and calculated how much those undervotes would yield if they were distributed among candidates in the same percentages as the other votes in each precinct. Significantly, he also attributed Gore’s relatively poor “pick up” of new votes (in the precincts that were counted) to mistakes made in the hand-counting process, which he figured dampen whatever swings occur. He then built this 8% error factor into his model.

Reading these posts makes me wistful for the long-gone golden age of blogging. But its spirit lives on in newsletters and podcasts, both of which allow independent pundits and reporters to do compelling things without a big-media budget.

Missing history

As fascinating as it was to rummage through online coverage of the 2000 Florida recount, the experience also left me downhearted—not about what I saw, but what I couldn’t. It’s painfully clear that a vast amount of the material that got published back then is no longer available on the internet and is quite possibly gone, period.

Websites run by large companies have a dismal record when it comes to bothering to keep their old content available: Just last year, Verizon deleted 20 years’ worth of Yahoo Groups in their entirety. (Independents such as Dave Winer are far more diligent about not trashing their past.) The Wayback Machine is invaluable, but its collection of vintage webpages is spotty, especially for the era in which the 2000 election and recount happened. For instance, I couldn’t rustle up a single WashingtonPost.com page for November or December of that year.

Vintage online audio and video from the pre-Flash days are so scarce as to feel borderline-mythical. They were streamed using now-obsolete server software to browser plug-ins that no longer exist; playing them is a near-impossibility for technical reasons, and they aren’t part of the Wayback Machine’s backups. Did ABC News and The New York Times keep copies of their Political Points webcast, just to pick one example of something that might be worth revisiting? It’s conceivable that they’re filed away somewhere on a hard drive in New York. But for now, it’s easier to dig up dead-tree news coverage of the 1800 election.

Someday the election of 2020, like the one of 2000, will be history. It would be nice to think that we’ll do a better job of preserving the digital record of how people reacted to it. And the time to start making that happen is now.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.