I’ve seen the future, and it’s made of circles and squares.

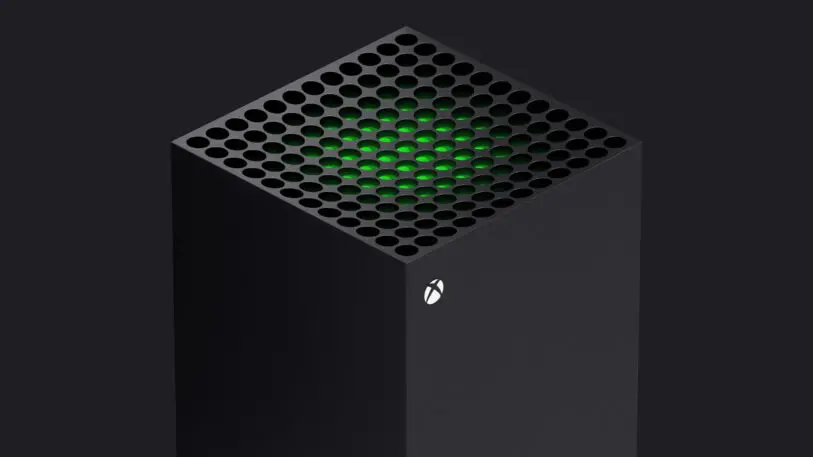

On November 10, Microsoft will launch the next generation of game consoles, with two systems aimed at different customers. The first is a $500 black monolith dubbed the Xbox Series X—what will be the most powerful console on the market. The other is designed like its shadow, if shadows were white: It’s a thinner, white rectangle with a prominent black circle dubbed the Xbox Series S—what will be the most affordable new console on the market at $300.

“We think about our console as part of the environment you live in as our customer,” says Phil Spencer, executive vice president of gaming at Microsoft. “While there’s an opening of the box and you want that to be fantastic, once you put that console wherever you put it, we hope you never have to touch it again, hope you never have to hear from it again, and it just plays great games. . . . It’s not the center of attention.”

As if to prove this point, Spencer conducted an interview in July, from his home office, before the Xbox Series S design was made public. Look into the background, and you can see the S peeking out between a stack of books. And no one noticed until Microsoft revealed the ruse last week.

“We really built this strategy around that—play the games you want, with the people you want, on the devices you want or already have,” says Spencer. Why? Because in the year 2020, when dozens of mobile devices from all sorts of manufacturers play Fortnite just fine, a box you buy every eight or so years to play new video games on your TV is a dated idea. Which is why Microsoft designed the new consoles, not as the star of the show, but as one component in its larger Xbox ecosystem, which includes a subscription called Game Pass and the option to stream these games to Android phones on xCloud. Plus, in an unprecedented move, last-generation Xboxes will play many upcoming Xbox games, like the next Halo. And the new Xboxes will play all the old Xbox games people already have.

“Of course when I buy a game I should be able to continue to play that game [on the next generation],” Spencer says. “Console gaming is the only space out there where you lose access to [software purchases]. Can you imagine if that were true with phones or PCs?

“The high-level goal for us,” he adds, “is can we build a platform where more people want to play more games more often?”

Building a better Xbox

When Spencer was promoted to be the head of the Xbox division in 2014, he walked into a bad situation on the verge of getting worse. As previously detailed on Fast Company, when Microsoft launched its Xbox One console in 2013, it was $100 more expensive than its main competitor, the Playstation 4, and it actually had slightly less processing power, due to a future-forward user interface that included the Kinect voice and gesture camera, a larger focus on media content beyond games themselves, and even smart home functionality. These decisions left a lot for customers to criticize, and ultimately, a narrative developed that Sony cared about video games, and Microsoft didn’t.

“We’d started out in the [2013] holiday doing well. There was so much pent-up demand that our supply was outstripped. You come out of the gate and everyone is selling out of what they can make,” says Spencer. “Then in the next year you see the natural trajectory of where you’re going and the competition is going.” Microsoft’s trajectory didn’t keep up with Sony’s. Seven years later, even while the Xbox division is a multibillion-dollar, profitable business for Microsoft, the PS4 still outsold the Xbox One roughly 2:1.

“More important to me than any of the product stuff or business stuff was where my team was at. The Xbox team, being transparent, had lost some confidence as to why we were there,” says Spencer. “Were we building products for our reasons or our customer’s reasons? Was our ambition as a company outstripping what our customers wanted to see from our product?”

Spencer centered the Xbox team’s focus as “a gaming company,” and instructed them to build the entire Xbox product roadmap around that. Kinect was put to pasture. Experimental virtual reality integration appears to have been as well. Microsoft interviewed gamers about what the Xbox brand meant to them, what its legacy was in the gaming space. And they heard a word that harkened back all the way to the first Xbox made in 2001—a time when it had seemed like a joke that Bill Gates thought he could build a game console.

Power.

Power in a pizza box

Processing power wasn’t just important to the gaming narrative, it became part of the Xbox brand from when it first arrived as a beefy competitor to the Playstation 2. So in 2017, as the team began to consider what the next Xbox would look like, it wanted to carry on the legacy and figure out the most powerful design possible.

Around five designers worked with eight engineers, imagining processors that didn’t even exist yet. The design team began making foam mockups, with different shapes dependent upon the next Xbox’s internal architecture.

The engineering team had the notion, however, that the next Xbox could split the motherboard into two pieces (incidentally, the folding Motorola Razr remake launched in 2019 does the same thing). Such an architecture could fit inside a box that was thicker but less wide, kind of like we already see in hulking tower PCs. A single tornado of air could spin up through its center to cool the chips—which in turn would be able to produce 12 teraflops of processing power (2 teraflops more than the upcoming PS5). Little surprise, this mockup was dubbed “Tower,” according to Chris Kujawski, the Microsoft design principal who led the Xbox project.

“We’d line up 10-12 in home visits. We talk about gaming in general, how they use their console, high-level stuff . . . then we always took measurements of their room, how far they sat from the TV, and temperature readings for a thermal study,” says Kujawski. “Then we’d unveil these crude boxes . . . without much context other than, if this were the shape of the next-gen console, what do you think?”

The tower won. Not just because its monolithic design was visually compelling, but because of proportions that are more practical than you might expect. It’s a big box in your hands, yes, akin to the size of a commercial toaster. But because it’s not extreme in any one dimension, it can fit on a shelf that’s a mere 8-inches deep.

As Microsoft began to move forward with that design, the team also knew it wanted to create a less expensive version. As Spencer explains, having the most powerful console is key to the brand, but Xbox’s new customers tend to favor the less expensive permutations. These are generally released later in the console life cycle, but Microsoft wanted to offer it on day one.

Working from the Tower design, the team mocked up a form dubbed “Slice.” It had the same height and width as the Tower, but much less depth without features like a disc drive—it was as if the Slice was cut off the side of the Tower.

The Tower became the Xbox Series X. The Slice became the Xbox Series S. But especially within these minimal designs, the details mattered. And Microsoft chose to highlight a surprising detail of the industrial design as the console’s hero: the venting.

The art of the vent

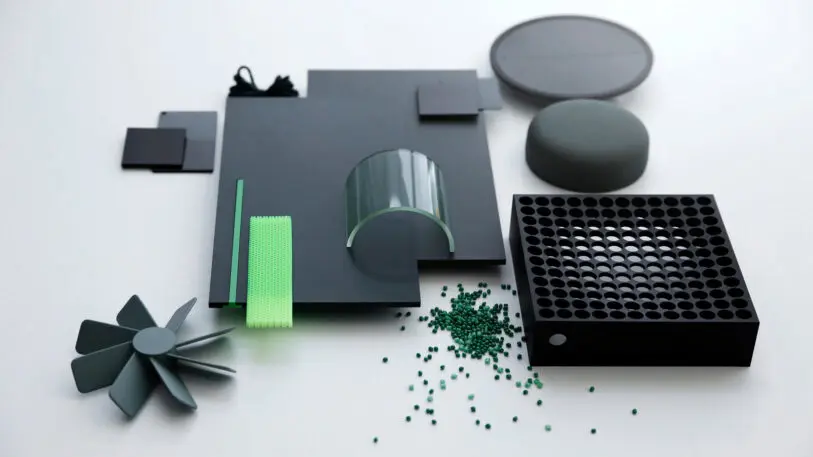

Microsoft’s design philosophy around the Xbox is dubbed “intelligent geometry.” “You start with pure forms and reveal personality through functionality,” explains Kujawski.

What that equates to in a practical sense is a visual language of squares and circles. Components like disc drives are boxes. There’s no way around that. Fans are circles. There’s no way around that, either. Instead of putting sculptural curves on the consoles to mask these components, Microsoft revealed personality through their functional shape.

That meant that the fan, and venting, became the star attraction. Given that the vents are 60% air, the Xbox consoles are essentially a celebration of negative space.

On the Series X, the vent is a stunning optical illusion. With a thicker perimeter than inside, it sinks into the box like a small depression. But the venting is actually stacked in two layers—the outermost is black, and the innermost is green. That means as your eye scans over the console, the green ripples and reveals itself, like a visual Easter egg. As Erika Kelter, senior CMF designer with Microsoft, explains, this is the “second read” of the device, which “invites you to come closer and explore.” It’s just two layers of plastic, and yet, it looks electric. And if you have enough light, you can even see the fan, too.

The Series S, in particular, will look quite familiar to anyone who has studied the work of renowned industrial designer Dieter Rams, namely his midcentury work at Braun (like his 1958 L 2 speaker). Gary Hustwit, a documentarian who made a whole movie about Rams, spotted the similarity as quickly as we did—suggesting it was so similar that the S had to be an homage.

The final, major piece of design work was done around the Xbox’s controller. In order to reach a wider audience (namely of younger players with small hands), the design team wanted to tweak the shape of the controller, but without tens of millions of customers losing their muscle memory. And so after lots of testing—players invited into the design studio, trying prototypes while being studied closely—the team came up with a refined design. Among the tiny adjustments were shaving roughly a millimeter off each of the controller’s front shoulders and integrating the top triggers as a more continuous curve.

Whereas the former design fit the 5th to 95th percentile of hand sizes, the new design fits the 3rd to 95th percentile of hand sizes. “The result we want is that you pick it up and don’t know it’s different . . . but for someone younger to pick it up and feel it’s easier,” explains Kujawski.

The future of Xbox is not just the Xbox

But perhaps the most radical design decision around these new boxes has to do with the business plan. Yes, the Series X is $500 and the Series S is $300. However, taking inspiration from the smartphone industry, Microsoft is offering a 0% installment plan that also incentivizes players to sign up for its Netflix of gaming, Game Pass.

Through these plans that are bundled with a variant of Game Pass, you can buy a Series X for $35/month for two years, or an S for $25/month for two years.

So which piece of the Xbox business is profitable for Microsoft? Is it the hardware? The software licensing for games that want to be on the Xbox? The subscription services like Game Pass? These are breakdowns that Microsoft doesn’t share, but Spencer implies that Game Pass, while key to the company’s long-term strategy, is not maximized for profit today.

Microsoft understands that the Xbox business is much larger than the Xbox console itself, and its latest generation of hardware is just one component in the ever-growing world of gaming.

“Microsoft is in the gaming business for the long run, we want to be a platform where hundreds of millions or billions of players can find somewhere to play,” says Spencer. “Building walls around Xbox, so the only way you can continue the experience you love is to buy a new console this fall—for us, it doesn’t seem in line with the values we have as a team.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.