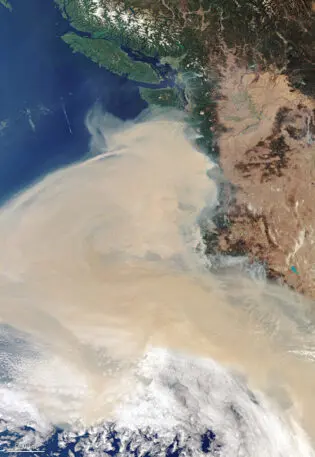

As massive wildfires burn in California and Oregon, the air has been filled with so much smoke that air quality ratings in some places have literally gone off the charts. The EPA’s Air Quality Index, which gives an air quality score based on the level of pollutants such as PM 2.5, the tiny particles produced by burning wood, considers a reading of 200 unhealthy and 300 hazardous, creating emergency conditions. In Bend, Oregon, this weekend, the official AQI value was over 500. In Eugene last week, PurpleAir, a network of backyard sensors, registered readings over 700.

What does the smoke mean for the millions of people who have been exposed? As wildfires burn, they spew huge amounts of particulate matter, along with toxic gases such as carbon monoxide and nitrogen oxides, and some of the emissions can react to form other pollutants such as ozone. Small particles are particularly dangerous because they can make it deep into your lungs; even tinier particles can penetrate the lining of the lungs and enter your bloodstream.

“It’s hard to tease that out,” he says. “We do know from air pollution in general, however, and this is where we’d be making assumptions, that long-term exposure reduces life expectancy—you’re just not going to live as long if you’ve been exposed.” Someone living in a city with higher average levels of pollution is more likely to die sooner than someone in a city with cleaner air, all else being equal. It’s not clear yet how a short spike in pollution from a fire compares to higher everyday pollution from things like cars or burning coal. But as major wildfires become more common and pollution spikes on an annual basis—something that didn’t happen regularly in cities such as Seattle or San Francisco in the past—it’s likely to have an effect.

Climate change is leading to more major wildfires as the temperature warms. Fire seasons are longer; warmer ground temperatures make the atmosphere more unstable, leading to more lightning strikes like those that started thousands of fires in California in August. The warmer atmosphere also sucks moisture out of wood, making fires more intense. “It’s easier for fires to start, easier for fires to spread, and that means that there’s more fuel available to burn, which means more smoke,” says Mike Flannigan, a professor of wildland fires at the University of Alberta. “It also means a higher-intensity fire, which is challenging to impossible to extinguish.”

The bigger the fire, the more smoke can reach cities far away from a burning forest. “A smaller fire is usually a lower-intensity fire, so it’s burning less materials, so there would be less smoke,” he says. “With a smaller fire, the smoke will mostly be local. The more intense the fire, the more the smoke column goes higher up in atmosphere. Smoke can circle the globe.” Smoke from the current wildfires on the West Coast has reached as far as Germany. Better forest management can help mitigate the problem, as controlled burns of smaller fires can make megafires less likely. But as climate change continues, air pollution from fires is likely to get worse. “We expect more and more fire in the future, more smoke in the future,” he says.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.