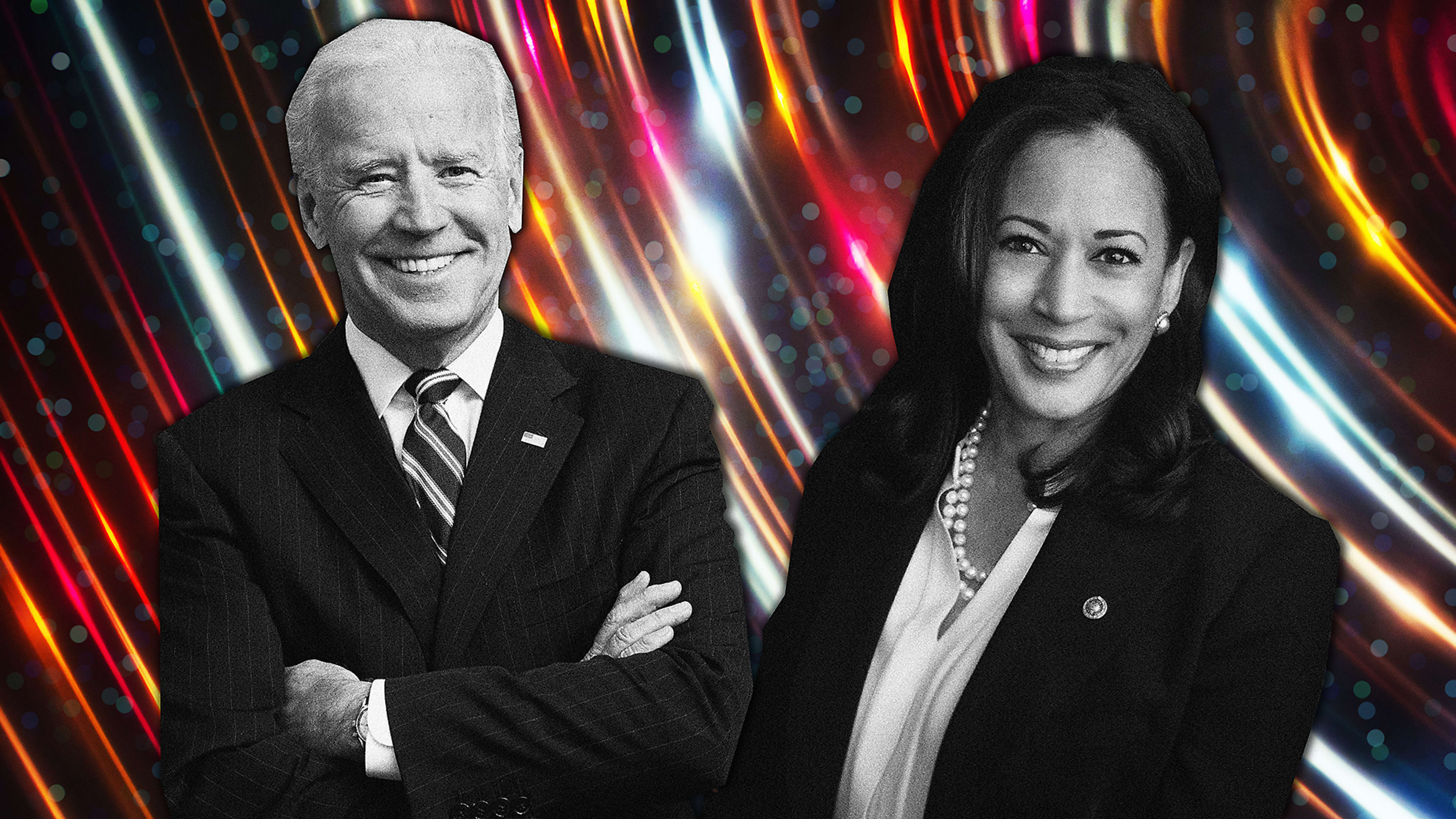

If the Biden-Harris ticket wins in November, it will mark the first time that a sitting vice president is a digital native. Not only did Kamala Harris grow up digital, but she’s also spent much of her adult life in and around Silicon Valley, and her statewide campaigns have been backed by some of Silicon Valley’s top Democratic power brokers, including Sheryl Sandberg, Facebook’s chief operating officer, and Marc Benioff, chief executive of Salesforce.

But being a digital native doesn’t necessarily mean that Harris will chart a wise course when it comes to regulating technology, particularly AI and facial recognition. As someone who has founded two AI startups, holds a dozen AI-related patents, and has worked on more than 1,000 AI projects, I can tell you that the way AI behaves in the laboratory is very different from what happens when you unleash AI into the real world. While Harris has proven that she understands the importance of this technology, it’s not clear how a Biden-Harris administration would regulate AI.

Harris has already shown a keen interest in how artificial intelligence and facial recognition technology can be misused. In 2018, Harris and a group of legislators sent pointed letters to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), and the Federal Bureau of Investigation, documenting research showing how facial recognition can produce and reinforce racial and gender bias. Harris asked that the EEOC develop guidelines for employers on the fair use of facial analysis technologies and called on the FTC to consider requiring facial recognition developers to disclose the technology’s potential biases to purchasers.

As Harris pointed out in a 2019 address, “Unlike the racial bias that all of us can pretty easily detect when you get stopped in a department store or while you’re driving, the bias that’s built into technology will not be easy to detect.”

Harris posited a scenario in which an African American woman seeks a job at a company that uses facial analysis to assess how well a candidate’s mannerisms are similar to those of its top managers. If the company’s top managers are predominately white and male, the characteristics the computer is looking for may have nothing to do with job performance. Instead, they may be artifacts that only serve to perpetuate racism, while giving it the veneer of science.

While Harris has a track record of asking fundamental questions about how AI is implemented, it’s still unclear how exactly the Biden-Harris team views the government’s role in addressing algorithmic bias. Facial recognition is still a rapidly evolving part of AI, and it has been a lightning rod for criticism. However, AI is much more than facial recognition.

AI is the defining technological battlefield of our time, and countries have adopted very different battle strategies. China seems to believe that access to vast volumes of data is key to AI supremacy and is willing to accept almost any implementation of AI, including a vast, secret system of advanced facial recognition technology to track and control the Uighurs, a largely Muslim minority. The EU has taken a very cautious stance and has considered a five-year ban on facial recognition technologies in public settings. A handful of U.S. cities have proposed similar bans, as activists widely believe that facial recognition in its present form is unreliable and threatens civil rights. But an ultrasafe regulatory approach doesn’t necessarily lead to better outcomes. The EU has previously embraced heavy-handed technology regulations that don’t really solve the underlying problem, as in the case of the now-ubiquitous “cookie warnings” that most people just click through without reading.

The U.S. faces a difficult challenge: preventing AI from being used in harmful ways while at the same time not unreasonably constraining the development of this critical technology.

In a best-case scenario, the government establishes clear societal expectations of what is and is not acceptable in AI and enforces compliance. The government doesn’t tell technologists how to change their technology—it tells them what the societal goals are and punishes violators with fines or other restrictions. That way, the government isn’t constraining the development of AI technology—it’s setting clear objectives and boundaries.

A far worse scenario would be for the government to step in with a heavy hand and mandate specific technological requirements for AI. For example, an activist government might be tempted to “solve” the problem of algorithmic bias by making AI developers remove the variables in the datasets that indicate a person’s race or gender. But that won’t fix the problem.

If you remove the variables that explicitly refer to race or gender, the AI will find other proxies for that missing data. Outcomes can still be affected by a person’s gender through other means: Data fields such as employment (schoolteachers tend to be disproportionately female; construction workers are disproportionately male) or age (women tend to live longer) can also play a role in perpetuating bias. Similarly, the AI will find proxies for race, even if the government has mandated that the race field be removed from the data set. Excluding a variable doesn’t mean that the AI can’t represent it in some other way.

Even an apparently well-meaning requirement, such as mandating that all AI development steps need to be documented, could have unexpected consequences that affect AI development. It may push organizations toward automated tools for experimenting with and selecting machine learning models because automated systems are better able to document every decision taken. It may also give large organizations with better processes a leg up over a scrappy startup team that may not be positioned to have the same kind of process rigor as an academic or corporate lab. Moreover, if the models themselves have to be “explainable,” then many popular “deep” approaches to machine learning may need to be abandoned.

That’s why you don’t want Congress to mandate specific technological fixes for something as complex as AI. Congress should be in the business of making its nondiscrimination goals very clear and holding companies accountable if they fail to live up to them. While larger tech companies may be able to shrug off the risk of penalties, fines proportional to the economic impact of the AI system may be one way to make the cost of violating these regulations painful enough even for big corporations.

I hope a Biden-Harris administration would live up to Joe Biden’s often-voiced promise of listening to the experts. In the case of AI, listening to the experts means bringing together a broad group of people to fashion a cohesive national AI policy, one our country needs in order to stay at the forefront of AI internationally. We need ethicists and academicians and social justice activists to be part of this vital process. And we also need a place at the table for people who have actually implemented AI projects at scale and have seen the real-world consequences of AI—intended and unintended.

Taking visible “action” on racial bias in AI is easy. Solving the problem at scale without harming U.S. competitiveness in AI is hard. If the Biden-Harris team wins, let’s hope the new administration decides to solve the hard problem.

Arijit Sengupta is the founder and CEO of Aible.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.