“The Macintosh architecture is going to peak next year sometime. And that means that there’s enough cracks in the wall already, and enough limitations to the architecture, that the Mac’s pretty much going to be everything it’s ever going to be sometime next year.”

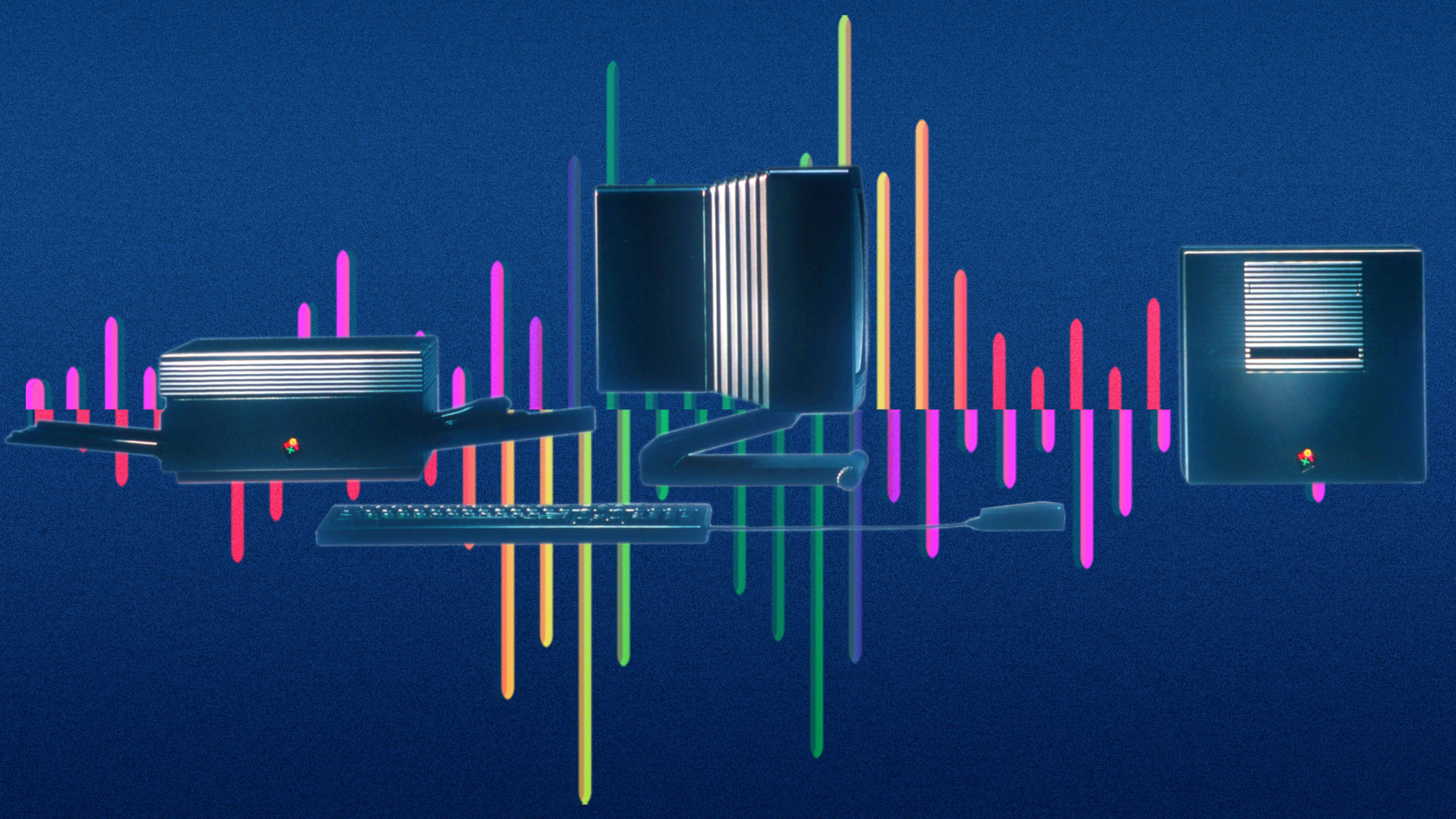

A tech CEO is onstage helpfully explaining that the Mac’s expiration date is imminent. More important, he’s about to introduce us to a new computer designed for the next decade. I am in a distant seat among his audience of more than 2,000 at Boston’s Symphony Hall, where the anticipation in the air is thick enough to induce a contact high.

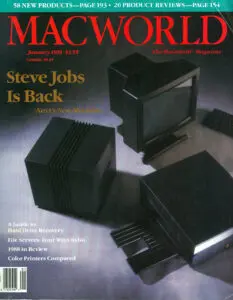

After all, we are among the lucky few who will hear about the NeXT computer directly from Steve Jobs himself.

What we were witnessing on the evening of November 30, 1988 wasn’t the NeXT launch event. That had happened seven weeks earlier at San Francisco’s Louise M. Davies Symphony Hall, before 3,000 invited developers, educators, and reporters. Jobs was now giving a second performance of the same basic presentation at the monthly general meeting of the Boston Computer Society. It was open to all members, and therefore a much more public affair than the exclusive San Francisco version.

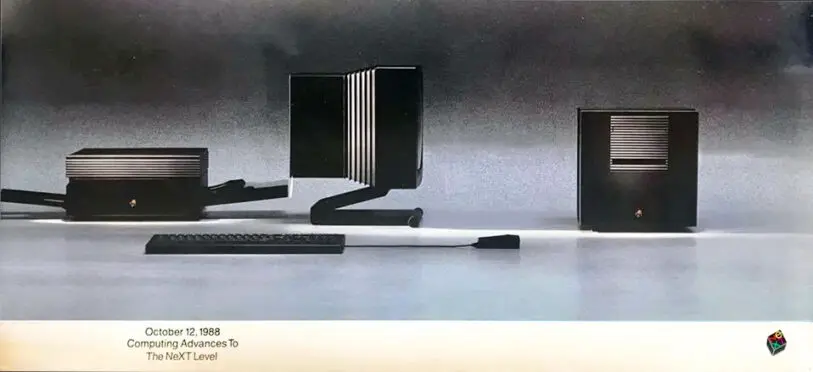

Sitting there being wowed by the machine was an oddly bittersweet experience. At $6,500, it was so far out of my price range that desiring one was purely aspirational, like lusting after a Lamborghini. (Not yet a tech journalist, I had no reason to expect I’d get to touch one in a professional capacity—in fact, I still haven’t.) But at evening’s end, as we streamed out of Jobs’s reality-distortion field back into the chilly Boston air, each of us got a NeXT product to take home: a glossy poster depicting the cube in all its unattainable glory. I tacked mine up next to my desk at work the next morning, and remain sorry that I didn’t keep it.

When I asked Jonathan Rotenberg—who had cofounded the Boston Computer Society in 1977 at age 13 and as its president turned it into the nation’s largest user group—if it had made videos of its meetings, the answer turned out to be: yes, sometimes. To my delight, this inquiry helped inspire a project to digitize and share those vintage videos. The NeXT session, however, was not among the ones that had been videotaped.

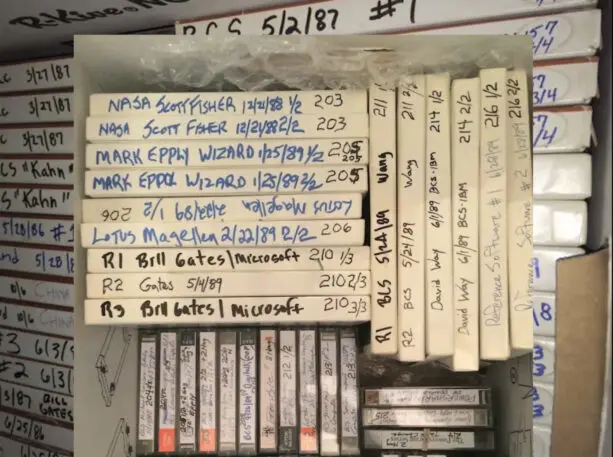

Then something remarkable happened. I heard from Charles Mann, who had made professional audio recordings of dozens of BCS meetings and other computer-related events in the 1980s and early ’90s. Unbeknownst to me, he had sold many of them on audiocassette at the time, under the name The Powersharing Series. In 1988, when I was basking in Jobs’s presentation, Mann was elsewhere in the hall recording it. Here it is in its entirety:

And that’s just for starters. Mann made his first recordings at a computer fair at New York’s United Nations International School, held on a September weekend in 1983 and featuring a stellar lineup of speakers such as Jobs’s Apple cofounder Steve Wozniak and AI guru Seymour Papert. “With 30 amazing computer pioneers presenting, it seemed to me almost a crime against our national cultural memory not to record these events,” he remembers.

Over the next seven-plus years, Mann recorded talks and presentations in Boston and New York—often several of them in a given month—adding up to an audio history of a crucial era in tech. The entire 92-recording archive is available on a USB drive for $60; with 200 hours of audio and 16 more of video, it’s a vast amount of hitherto unavailable material for the money.

Actually hearing these people in vintage recordings is an entirely different experience from reading about them, or (if you were alive and paying attention at the time, like me) relying on distant memories. To pick just one example, pundit-entrepreneur Adam Osborne—whose name has unfairly lived on mostly as a synonym for foolishly pre-announcing a product—gets to speak for himself, in his regal British accent, in two recordings. Here he is telling BCS members that software will only get buggier as computers get more powerful, a prediction that has held true.

“You look at that list of the speakers, and it’s like, these are things that have to be kept forever in the archives of our industry,” says Dan Bricklin, who cocreated VisiCalc, the first spreadsheet program, with Bob Frankston. (Their company Software Arts subsidized the videotaping of some BCS meetings.) Bricklin is on three of Mann’s recordings, including one of a 1985 New York PC Users Group meeting where he told the story of VisiCalc’s rise and fall.

The Powersharing Series preserves a time long past, and computing nerds will revel in sessions featuring once-mighty names such as Atari, Commodore, and Radio Shack. In 1985, for instance, a month after Commodore announced its groundbreaking Amiga computer in New York City, president Tom Rattigan came to Boston to show it to BCS members and argue that it left the Mac in the dust.

Entertaining though these recordings can be, their value is far from purely nostalgic. “Now it seems everything is recorded, but in those days, we were just exploring and having fun,” says investor Esther Dyson, whose 1985 presentation on “artificial knowledge”—back when she was best known for her PC Forum conference and Release 1.0 newsletter—was the first BCS meeting Mann recorded. “But why it matters is that those explorations and that fun were in the end quite significant. It’s always useful to look back and to realize that even though the tech itself might seem quite primitive today, the people were already sophisticated. We know a lot more facts, and we can do more things, but I’m not sure we have gotten that much wiser.”

The Boston ritual

Though the NeXT cube’s grandiose demo at Symphony Hall may have been the ultimate Boston Computer Society meeting, it was also part of a well-established tradition. For years, major computer companies had been using the user group’s monthly general meeting to introduce new products to consumers—including the 1984 Macintosh, which Jobs had brought to Boston days after revealing it at Apple’s annual meeting in Cupertino.

In 1986, the year after he left Apple, Jobs came to Boston to speak at Harvard Business School on his life as an entrepreneur. After the talk, he chatted with BCS president Rotenberg at a bar in Harvard Square and proudly showed off the NeXT logo, which famed designer Paul Rand had delivered to the company in the form of a book explaining his work. As Jobs presented Rotenberg with a copy of the volume, Rotenberg remembers, NeXT’s shiny new logo “seemed to me like it was the center of Steve Jobs’s universe at that point. And maybe it’s just because it was something he could talk about.”

At that time, the NeXT computer itself remained an unannounced enigma. But Rotenberg invited Jobs to conduct its East Coast premiere at a BCS meeting when he was ready. In the fall of 1988, he was.

As with the Mac’s 1984 introduction, the BCS meeting would be a loose re-creation of the official launch in the Bay Area, except held in Boston and open to members of the general public—BCS members and a certain number of random interested parties who wangled their way in. With Jobs having largely disappeared as an industry figure, his reemergence with a new computer made for major events on both coasts. “Just the fact that it was Steve Jobs, his next thing, made it very, very noteworthy in itself,” Rotenberg says.

According to Randall Stross’s 1993 book Steve Jobs & the NeXT Big Thing, Jobs chose to introduce the NeXT in San Francisco’s Davies Symphony Hall in part to show off the machine’s impressive audio capabilities—16-bit CD-quality sound and what Jobs was to describe as a “Walkman stereo headphone jack.” Along with a duet between the cube and a human violinist, the presentation was to feature additional synthesized music, sound clips of speeches by JFK and Martin Luther King Jr., and a demo of a voice recording being attached to an email. All of which was heady stuff at the time.

Other elements included a slick film showing motherboards majestically traveling through NeXT’s robot-controlled factory in Fremont, California, a prototype for the hardware-fetishizing videos that would become a staple at Apple events. But as with any Jobs keynote, the main attraction would ultimately be the man and his machine, as he showed what the company had built and what it could do.

Long unavailable, video of the Davies Hall event was uncovered during production of the 2015 Aaron Sorkin-scripted film Steve Jobs. (Part of the movie is set backstage at the event, though it’s the furthest thing from a historical reenactment, starting with the fact that it’s been relocated from Davies Hall to the War Memorial Opera House across the street.) Assembled from two VHS tapes, the video is murky enough that it’s prefaced with a note expressing hope that a better copy will resurface. Still, the manufacturing film and a press conference at the end (look for NeXT investor Ross Perot) are in better shape, and the whole thing is worth a look.

Once Jobs returned to Apple and began doing product keynotes regularly, they became known for their unassailable level of polish. By comparison, the San Francisco NeXT event was not a model of discipline. For one thing, it ran over two hours—a long time to keep an audience engaged even if you’re Steve Jobs. (Eighteen years later, in what many would regard as the single most effective product launch of all time, he unveiled the first iPhone in an hour and 19 minutes.)

According to John C. Dvorak’s cranky account in the San Francisco Examiner, the NeXT event started 45 minutes late. Jobs begins by noting that, “I haven’t done this in a few years, so I’m a little nervous.” Later, he skips a prepared section about Adobe, explaining that the presentation is running late and needs to wrap up so the hall can be cleared for a concert that afternoon.

In short, the Davies Hall launch felt like a rough draft. The Boston version would give NeXT a chance to tune it up and do it all over again.

Steve Jobs’s power as a presenter mostly came from what he said and how he said it, rather than how he looked.

“That was so seared in our collective experience, people being locked out, that we really, really planned it out this time for the Symphony Hall thing,” Rotenberg says. “When people arrived, we had different colored cards that they got so that they would get in in the order that they arrived.”

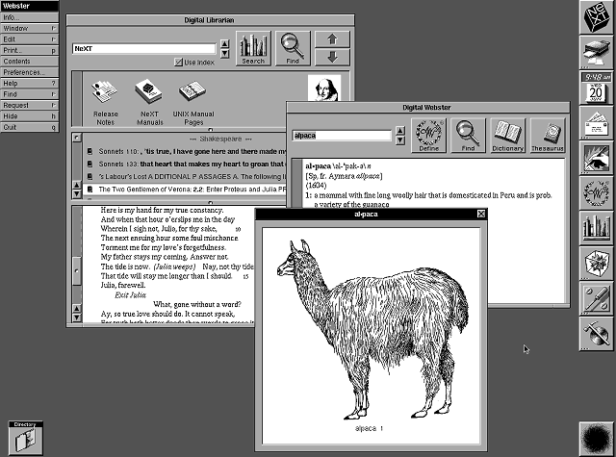

Those of us who made it inside saw an event that ran under 90 minutes—essentially a tighter edit of the San Francisco premiere. It also got off to a more rousing start, with a crowd-pleasing video introducing the cube’s NeXTStep operating system as the next advance beyond text-based interfaces and the Mac. That video—created by Keith Ohlfs, whose icon designs helped define the NeXT interface—was part of the San Francisco edition, too, but it didn’t appear until 40 minutes in. And here it is—apparently in a longer version than shown in Boston, since it doesn’t sync up with the audio:

I’m glad that this video survives in such pristine shape. But one of the striking things about Mann’s recording is how well it works without a visual component. Before I listened to it, I assumed that an audio-only version would be—at best—only half as rewarding as a video. Not so: It’s comprehensible and rewarding on its own, even though you can’t see the computer that is captivating all those BCS members.

Maybe that shouldn’t be so surprising. After all, Steve Jobs’s power as a presenter mostly came from what he said and how he said it, rather than how he looked. This can be tested: Try watching any Jobs presentation with the sound turned off, and then again with audio, but no picture. Which version did you find more compelling?

Mann, who considered himself an “on-scene agent and ‘seeing eye’ guide” for listeners, did provide occasional helpful interjections on his tapes when something wasn’t entirely clear from the soundtrack alone. But as he recorded presentations, he found they didn’t need much commentary: “When the speaker projects his computer screen up onto the screen, he typically narrates what we are looking at, so usually no added narration is necessary.”

Indeed, even chunks of the event when Jobs is demonstrating software are surprisingly coherent when you can’t see what he’s showing—such as in this section covering NeXTStep’s breakthrough user interface.

Vintage video of tech-industry events in darkened halls, such as the San Francisco NeXT launch, is never exactly a high-def experience, and is sometimes impossible to make out at all. The Powersharing audio programs, by contrast, usually sound like they could have been recorded yesterday. That’s especially true of this event: Though Mann and his sound man, John Cameron (also of PBS’s Nova), typically had to set up their own microphone, the NeXT audio-visual team let them plug their reel-to-reel tape recorder into the main system. “With the team NeXT had there managing the soundboard, we were assured a really clean audio feed,” Mann says.

Toward the end of his presentations in San Francisco and Boston, Jobs quoted Polaroid founder Edwin H. Land, one of his heroes. “He said, ‘I want Polaroid to stand at the intersection of art and science,’ and I’ve never forgotten that, and that’s what a lot of us want for NeXT as well,” Jobs explained. And then he introduced a symphony violinist who played Bach’s Violin Concerto in A Minor as a duet with the NeXT Cube. (It was likely a coincidence, but Land was also known to incorporate live classical music into events he presided over.)

All of this presaged the “Stevenotes” to come once Jobs returned to Apple. He sometimes said toward the end of a presentation that Apple tried to sit “at the intersection of technology and liberal arts,” a twist on Land’s declaration. Particularly when the iPod was involved, Apple often concluded with Jobs introducing a musical act, from U2 to Kanye West. Such performances became so familiar that some people were startled when a launch ended without one.

Back in 1988, however, a musical performance at a computer unveiling was a novelty, even before you got to the fact that it was a collaboration between human and machine. I still remember sitting in Symphony Hall, feeling the sort of awe that Jobs must have wanted to generate.

At the NeXT cube’s West Coast debut, violinist Daniel Kobialka of the San Francisco Symphony had performed. For the Boston version of the event, NeXT contacted the concertmaster of the Boston Philharmonic, who ended up recommending assistant concertmaster Helene Pohl for the job. “I was still a student, so it was terribly exciting,” remembers Pohl, who has been first violinist for the New Zealand String Quartet for more than 25 years. She says that Jobs’s original idea for the performance involved the NeXT monitoring her playing and adjusting its own part accordingly; when that proved impractical, she had to let the computer take the lead.

“Since then, of course, technology has moved on considerably,” Pohl says. “I did feel that it was a glimpse of the future. And given all the socially distanced music-making that’s going on in 2020, it was a prescient idea.”

After hiring Pohl to perform at Symphony Hall, NeXT also flew her to San Francisco to duet with the cube for “News from Earth,” an episode of The Koppel Report, a series of prime-time ABC News specials hosted by Nightline‘s Ted Koppel. Aired on December 26, 1988, the show was presented as a sort of time capsule for the benefit of any extraterrestrials who might someday pick up the broadcast. It featured notables such as Richard Nixon, Desmond Tutu, Jane Goodall, Jean-Michel Cousteau, and Stevie Wonder. And Steve Jobs, who presented a pocket edition of part of his NeXT presentation with a demo of the NeXT’s digital book of quotations and an excerpt from Pohl’s performance.

Here are Jobs, Pohl, and the cube, with a snippet of Stevie Wonder at the end. Note that Jobs never mentions NeXT by name (“Hi, I’m Steve Jobs, and I make computers.”); presumably ABC was sensitive about the whole affair coming off as free commercial time.

History on tape

The audio of Jobs’s NeXT demo at the BCS—and dozens of other recordings—exist solely because Mann realized more than 35 years ago that the talks going on at computer user-group meetings and conferences were history in the making. A development economist who spent much of his time in other countries helping locals with food policy, he first got interested in computers because of their potential to aid his work in Tunisia. That led to him coproducing a video about the Apple II and VisiCalc in 1982. Because he believed that PCs were about power and sharing, he called this project The Powersharing Series.

The next year, Mann participated in the computer fair at the United Nations International School, cosponsored by the Big Apple Users Group and the New York IBM PC Users Group. With the event’s organizers preoccupied just making sure everything happened according to plan, they agreed to let him record the talks for distribution. In February 1985, Mann began recording other tech gatherings—many Boston Computer Society meetings, plus New York user-group conclaves and events at Harvard and Boston’s Computer Museum.

At the time, many people were just beginning to familiarize themselves with computers and were hungry for the sort of information Mann was preserving. And The Powersharing Series stood a chance at benefiting from a new age of personal audio that had dawned when Sony shipped its first Walkman in 1979. By 1982, the company had sold 5 million units, and countless imitators had sold millions more. Even if most of the folks strolling around with headphones on were listening to prerecorded music or mixtapes, there was now a market for spoken-word audio as well.

Mann wasn’t just prescient in realizing that such events had lasting value; he was also patient. Libraries did buy his initial set of tapes. But as hopeful as he was that people would listen to Powersharing cassettes to learn about the computer revolution, business didn’t really take off. By then, though, he believed in the project so passionately that he used a small inheritance to subsidize additional recordings, even though sales—at the Computer Museum gift shop and through the BCS’s magazine—were minimal. “Pretty much all of my Powersharing efforts went into recording the material for posterity,” he says.

This is rare, rare stuff; if you know of even one other example of surviving audio or video of Jobs and Wozniak talking about Apple together, I’d love to hear about it.

The end—and a new beginning

Ultimately, the biggest obstacle to The Powersharing Series wasn’t its short-term prospects as a business. Instead, it was Mann’s demanding day job as an international economist. Starting in 1987, his work took him to Africa for multiple monthlong trips a year. Though he managed to keep going for a while, he decided to postpone additional work on the series in 1991. The next year, he relocated to Malawi in Southern Africa for a four-year assignment as food security adviser to the country’s government. And with that, the Powersharing project came to an end.

Step one—getting Mann’s programs off ancient tapes and into digital form—was the most daunting challenge.

In the years that followed, Mann always planned to do something with the tapes to make them available again. It just took him a lot more time than he expected, in part because he began yet another career—as a documentary filmmaker—after retiring as an economist. (He will turn 86 in October.)

In 2014, Mann finally turned back to The Powersharing Series. “Little did I realize when I put all of the hundreds of tapes into storage that it would be 2019 before I would finally complete producing the series,” he says.

Step one—getting Mann’s programs off ancient tapes and into digital form—was the most daunting challenge. “There are few people that go and develop a passion like he did, and save things in a comprehensive manner,” says Gardner Hendrie, a trustee of Silicon Valley’s Computer History Museum, the successor to the Boston museum where Mann had done some of his recording. (Hendrie’s own history in the computer industry goes back to the 1950s, when he designed mainframes for RCA.)

After seeing Mann’s trove for himself and being impressed by its significance, Hendrie volunteered the Computer History Museum’s resources to handle the digital transfer process, permitting Mann to focus on editing and packaging the material for a new generation of listeners. Even that was a massive undertaking, which Mann ended up doing in partnership with Tom Frikker, a computer historian (and, at the time, computer science student) who’d also been involved with piecing together the video of the NeXT San Francisco launch.

NeXT forever

Just witnessing Jobs’s 1988 BCS meeting was the kind of experience a tech enthusiast is unlikely to forget. But as the group’s president and the guy who preserved the meeting for the sake of history, Rotenberg and Mann have recollections that are uniquely theirs.

In Rotenberg’s case, those memories aren’t entirely idyllic. “Steve was always one of my favorite people and greatest mentors,” he stresses. However, as pleased as Rotenberg was with how the meeting turned out, the behind-the-scenes aspect had been “one of the most hellacious experiences I’d had in my life, up to that point.” Rather than behaving like invited guests at a user group meeting, NeXT’s marketing people saw it as an opportunity to drape Symphony Hall in advertising banners and hand out brochures to arriving attendees, ignoring rules they’d agreed to follow. (“The purpose of your talk should be informational—not sales oriented,” instructed a guide Rotenberg had written for speakers.)

After the event, Rotenberg made it known to NeXT that he was toying with writing a scathing exposé for the BCS’s magazine. That prompted a call from Jobs. “He said, ‘I hear you’re not very happy with me, Jonathan,'” Rotenberg says. And I said, ‘Well, matter of fact, that’s true. We had had all of these agreements and all these different things up front that have not been adhered to.’ I summarized some of the different challenges. Then he said, ‘Well, you know, Jonathan, you can be an anal-retentive jerk sometimes.'”

Rotenberg’s reaction: “‘Oh my God, I think he just paid me a compliment because it’s from one anal-retentive jerk to another.’ It was the weirdest thing. I could not imagine a more obnoxious, stupid thing for him to say, but it actually made me feel better. And I decided not to write the article.”

That sign-off isn’t the end of the story of Steve Jobs and The Powersharing Series. Years later, when Mann was finally excavating his stacks of tapes for digitizing, he found some cassettes marked “JOBS.” He assumed they contained material from the 1988 BCS meeting. Instead, they turned out to be one more thing: a raw recording he had made of a November 1990 BCS meeting, as the Powersharing project was winding down. That night’s special guest: Steve Jobs. “It had passed even from my memory until I found it within the rest of the Jobs bundle,” says Mann.

Nowhere near as much of an extravaganza as the 1988 BCS NeXT meeting, the 1990 one recapped another NeXT event at San Francisco’s Davies Hall, where the company had launched four new machines, including its first color models. But a sizable chunk of the Boston version featured Lotus’s Improv, an inventive (though ultimately unsuccessful) spreadsheet application that was debuting on the NeXT platform. And Jobs himself did an extended demo of it.

Today, it’s a tad startling to listen to Jobs lavish his presentation skills on somebody else’s product. But NeXT had been criticized for a dearth of major software, so Improv mattered as much to NeXT as it did to Lotus. Jobs sounds like he’s genuinely into it, and even elicits laughs from the audience with gratuitous swipes at Chrysler (!) and cursor keys (!!) along the way.

November 1990 happens to be a historic month in the history of NeXT and computers in general—but not for reasons that had anything to do with the subjects of Jobs’s BCS appearance. Unbeknownst to those at the Boston meeting, a couple of NeXT users in Geneva were using the platform to assemble an information-sharing system for their colleagues at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research. They were Tim Berners-Lee and Robert Calliau, and they dubbed their NeXT-based system the “WorldWideWeb.”

If it weren’t for NeXT’s software being so robust and visionary back in the 1980s, Apple might not even exist in 2020.

The deal rewrote history by bringing Jobs back to Apple, eventually as CEO. But it also made NeXT’s Unix-based operating system the foundation of Apple’s own next-generation operating system, OS X, which revitalized the aging Mac. When the iPhone, iPad, Apple Watch, and Apple TV came along, they were built on customized versions of OS X.

Basically, if it weren’t for NeXT’s software being so robust and visionary back in the 1980s, Apple might not even exist in 2020, let alone having hit $2 trillion in market value. “Just the fact that [Jobs] came back at all and turned Apple around, that was really the thing that cemented his legacy,” says David Needle, who attended the 1988 San Francisco launch as editor of Computer Currents magazine. “And whether people recognize it or not, NeXT was the engine that made it happen.”

That’s an astounding achievement for the NeXT platform. But it’s utterly at odds with the theory that Jobs laid out for BCS members in 1988–that “computer architectures have about a 10-year life” consisting of five years of innovation and five years of profitable coasting. He didn’t argue that NeXT would buck that pattern. After asserting that the Mac would slough off starting in 1989, he added that NeXT would “peak, hopefully, in 1994 or ’95.”

Instead, we’re a fifth of the way into the next century after Jobs spoke and the Mac still matters, thanks in part to the brain transplant it got from NeXT. The iPad Pro I’m writing this article on is also a descendant of the NeXT cube I found so wondrous almost 32 years ago. And it’s a certainty that products Apple hasn’t even announced yet will have a little bit of NeXT in them.

In other words: 21st-century Jobs shattered one of 1988 Jobs’s fundamental beliefs about computing. As Esther Dyson points out, The Powersharing Series shows us how smart the technologists of the 1980s were. But it also proves that the future has a way of surprising even the people who create it.

The Powersharing Series recordings in this article are copyright © Powersharing, Inc. and used with permission. All rights reserved.

Recognize your company's culture of innovation by applying to this year's Best Workplaces for Innovators Awards before the extended deadline, April 12.