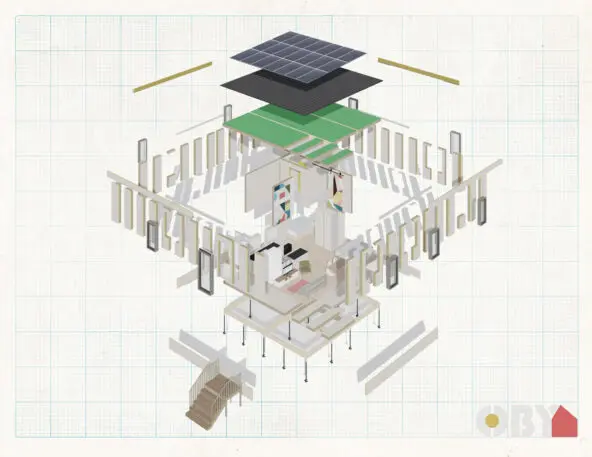

If you live in the Bay Area, a new coop wants to lease your backyard for the next 99 years. The startup, called Oby (“our backyard”), a spinoff of a company called CoEverything, is taking a new approach to affordable housing: It finds homeowners who are willing to share their backyards, then builds a tiny backyard house, which it rent at rates well below market rate. By making an agreement that lasts even when the main house on the property is later sold, the business model is designed to help create a long-term solution to the area’s housing crisis.

“With our company, we’re always looking at what the alternative models are that we can utilize to help build more affordable, accessible, sustainable housing,” says Declan Keefe, cofounder of CoEverything, which focuses on how to bring better practices to architecture and development. Backyard cottages are already relatively common in California. But they usually rent at market rate—something that’s out of reach for someone working as a barista, or, say, an elementary school teacher, even as rents start to drop in cities such as San Francisco as some remote workers relocate during the coronavirus crisis.

The basic agreement is similar to the model used by some other recent startups such as Rent the Backyard, a company that builds free tiny houses in backyards and splits the rent with homeowners. “We create a leasing contract with an existing homeowner who lives in the front house, and essentially allocate a portion of the backyard that will fit a backyard home,” says Keefe. “We agree that we’ll pay them a fixed monthly rate to let us use their backyard to build a house in the backyard and then rent it out at an affordable rate, and we agree to cover all the other costs and to manage it ourselves.”

The agreement lasts nearly a century. “When they sell their house, it transfers with the house,” Keefe says. “We’re purposefully doing that so that we can maintain the affordability long term.” Homeowners also benefit from the arrangement, getting a steady income stream of up to $500 a month to offset the cost of their own mortgage.

“It’s a way of distributing the labor so that we can actually do construction more quickly, but we can also spread around this value that’s being created from the expense of the house. Houses are expensive and people inherently see it as a bad thing,” says Keefe. “But I see it as a way to distribute wealth amongst our community. And so if we just had a model where we could have more people sort of touching each individual project, we could actually distribute the expense of that home itself amongst the community.” Arizmendi Construction Cooperative, a project associated with a popular worked-owned bakery chain in the area that is innovating to find ways to house its own workers, will serve as the on-site general contractor.

The coop, owned by both workers and community investors, is also taking a new approach to funding, making use of a new California law that allows cooperatives to raise capital without registering with the SEC, lowering the cost of fundraising. The model also allows the company to run a crowdfunding campaign. “The benefit there is we can actually have local ownership of these in a cooperative way,” he says. “So anyone who invests in the model will benefit. It’s a small return because we’re trying to keep costs low, but they can benefit over time from the value of owning the buildings in the backyards of their neighbors.”

Oby is in the process of signing its first contract with a homeowner in Oakland, with construction expected to begin on that project this fall.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.