In February, father and son Gregory and Travis McMichael killed Ahmaud Arbery as he jogged near his home in Satilla Shores, Georgia. State prosecutor George Barnhill justified the act by citing Georgia’s citizen’s arrest law, asserting that the killers were trying to lawfully detain Arbery, because they said they were suspicious that he’d attempted to burglarize a home. According to the Georgia law, a “private person” is permitted to arrest a fellow citizen if they’ve committed a felony and are trying to escape, even if the arrestor only has “probable grounds of suspicion.”

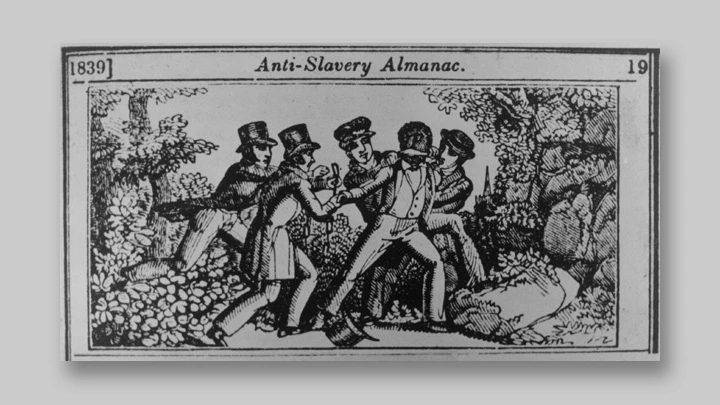

Georgia legislators are now debating the repeal of the archaic law, which has its roots in medieval England. The concept, transported to the Americas, is still the law in places across the United States. Though the law’s specifics vary state to state, it remains practically unchanged from centuries ago. But in its American renditions, it’s also influenced by the history of slavery and weaponry, and so has become a form of white privilege and violent vigilantism that still manifests itself today in far-right patrol groups and violence against minorities.

The history of citizen’s arrests, and their racist roots

Citizen’s arrests were first officially mentioned in the Statute of Winchester in 1285, when King Edward I explicitly instructed citizens to join the “Night Watch” and take part in “hue and cry”—public outcry and pursuit—when a fellow citizen is suspected of a crime, “until they be taken and delivered to the sheriff.” This community justice became an important part of keeping law and order in England, when it was impossible for “peace officers” to enforce the law alone.

That then became an important tenet of the early Anglo-American ideal of liberty, says Jason Opal, a professor of history at McGill University, who specializes in the foundation of the Americas. Involvement in community justice was a healthy means to ward off the threat of martial law and state oppression. Only the state could ultimately punish wrongdoers, but ordinary people enjoyed the right of “posse comitatus,” whereby they were deputized by sheriffs for the general good of the public.

As European colonizers brought the law to the Americas, “this liberal tradition took a horrifying turn,” Opal says, as it united with vigilantism, often racist. In 1661, Barbados passed the first slave code, which, among a slew of other regulations, required slaves who were away from the plantation to hold passes from their masters, and allowed any white man to stop them and ask to view those passes. Separately, the code established slave patrols, in which white men actively prowled for escaped slaves. The “posse comitatus” shifted from a public good to grounds for “chasing a runaway,” Opal says.

In the years since, structured police forces have developed, leaving less need for citizen’s arrests. Still, as cases around the country emerged, “courts began to provide more detail to guide private citizens,” writes Ira Robbins, a law professor at American University, in an extensive paper about citizen’s arrests in 2016. Through the 19th and 20th centuries, some state courts explicitly codified citizen’s arrests laws; other states still rely on common law precedents.

Most versions remain vague and open to interpretation. Some states allow citizen’s arrests only for felonies, some for misdemeanors, and some for any “breach of peace.” In Arkansas, the law only calls for “reasonable grounds for believing” that a person committed a felony. In Illinois, almost anything is fair game for an arrest except an ordinance violation. In Maine, citizens can arrest for lesser crimes only if they saw them committed, but for more serious crimes, probable cause is enough.

This creates an array of problems. “Many citizens do not comprehend the parameters of their authority,” writes Robbins. Even if the citizen has good intentions, if the arresting citizens are wrong, they are potentially liable for false arrest and imprisonment, or use of excessive force, and can be sued, especially in states like New York that put the burden of proof on the arrestor. It also opens up the door to abuse of power, and the risk of people carrying out personal vendettas. Robbins cites multiple cases of torture: “One arrestor detained the suspect, bound him, hung him from his feet, and struck him while he was questioned about items missing from a shop.” In this case, the court charged the arrestor with false imprisonment for administering “vigilante justice.”

When citizen’s arrests stray into vigilantism is concerning, and it’s an easy line to cross in the modern day. Robbins is particularly concerned with “private citizen volunteer watch groups” like the New York-founded Guardian Angels and the Xtreme Justice League, an armed patrol group that keeps “eyes and ears” on the streets of San Diego—all while wearing superhero costumes.<

“Virtuous violence” and vigilantism

In the U.S., today’s citizen’s arrests have also been made more dangerous by the prevalence of firearms. The 13th-century Statute of Winchester did require citizens to carry arms—”it is commanded that every man have in his house harness for to to keep the peace”—but the text notes lances, knives, “falces” and “gisarmes,” both curved, sickle-like agricultural tools.

Slave-patrolling militias were also required to be armed, “giving them powers that are unthinkable in Britain, unthinkable in the liberal tradition that it otherwise mimics,” Opal says. Today, deadly force is still permitted in some states’ adaptations. South Carolina’s law reads that, in certain cases, “a citizen may arrest a person in the nighttime by efficient means . . . even if the life of the person should be taken.” In 1989 a Michigan court decided not to curtail a citizen’s right to kill a fleeing felon. “It is regrettable, but sometimes necessary, to make use of deadly force,” the court wrote, because “the police cannot be everywhere they are needed at once.”

Guns have become a “totem” for white privilege, Opal says, a singular right that many feel has been lost since the Civil Rights era. Racist elements now combine with specific gun rights, such as stand-your-ground laws, present in 27 states, which allow people to use lethal force to if they feel threatened, regardless if they are able to retreat; and castle doctrines, which allow them to shoot to kill a trespasser on their property in the name of self-defense. This law led to the murder of Trayvon Martin by George Zimmerman, a neighborhood watch coordinator, and was found justifiable by a court. Such laws can lead to groups like Boogaloo, a mysterious far-right posse often described as vigilantes, who have deputized themselves to patrol Black Lives Matter protests and marches with assault rifles.

A recent example of such laws is a new directive by ICE, which called on ordinary citizens to sign up for a six-week academy to learn how to detain undocumented immigrants. The agency sent letters to selected citizens to encourage them to apply and be selected as one of the 10 to 12 admitted to what Chicago alderman Rossana Rodriguez has described as a “vigilante academy.” The letter says the program will include “defensive tactics, firearms familiarization, and targeted arrests.” Opal says of the modern-day hue and cry: “That is just catastrophic. I cannot imagine a good or legitimate place for that in anything approaching a democratic society.”

And, it leads to cases like the killing of Ahmaud Arbery. Last week, a House panel in Georgia started debating whether to revise or repeal the state’s citizen’s arrest law, which was established in 1863 to allow white people to able to capture slaves fleeing to join the Union Army during the Civil War. As proceedings began, Democrats argued that it still unfairly targets Black people, one citing the racist history: “It’s why the pain resulting from Mr. Arbery’s murder in connection with this statute resonates so loudly,” said Representative Josh McLaurin, “because it has those echoes of trying to chase and trap another human being.”

Some Democrats reasoned that the law could be kept in some cases, such as for “private police,” like security guards, who need to act when there aren’t public police on site, or for storeowners to detain robbers until police arrive, known as the “shopkeeper’s privilege.” Robbins, the author of the academic paper, agrees with massive reform on a national level, and agrees with these two exceptions, also adding that it should be retained for police in hot pursuit of a criminal when they enter another jurisdiction, where they effectively become ordinary citizens. Otherwise—in a draft of a reform bill that he writes up in full as the “Anti-Vigilante Act”—the solution is to abolish citizen’s arrest for the private citizen and for private citizen watch groups.”

Though Opal says that citizen’s arrests could work in a society that’s not so heavily armed—as it originally did—it needs to be abolished in the current condition of the country. The ultimate problem for Opal is that, it’s letting people make the decision themselves about who has the authority to commit violence—and who that violence should be directed against. “It is deputizing people to be violent, or to have the power of the state, which means that it is saying that other people do not have the power.” And it’s clear who’s being subjugated. “Black people, especially Black men, have [a] long history of being on the losing end of those guns.”

Keeping the antiquated laws intact would “ratchet up even further racial violence,” he says. “I think it’s a monumentally bad idea in an age of monumentally bad ideas.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.