Some of the most unique pieces of modernist architecture from the 20th century are also the most endangered. Bold, and often comparatively weird, the modernist architecture of the mid- to late-1900s is now falling apart. With new and experimental forms that resist traditional conservation efforts, the buildings are victims of their innovation.

But they’re not lost causes just yet. Funding from the Getty Institute has just been awarded to help develop conservation plans for some of the world’s most extraordinary examples of modernist design.

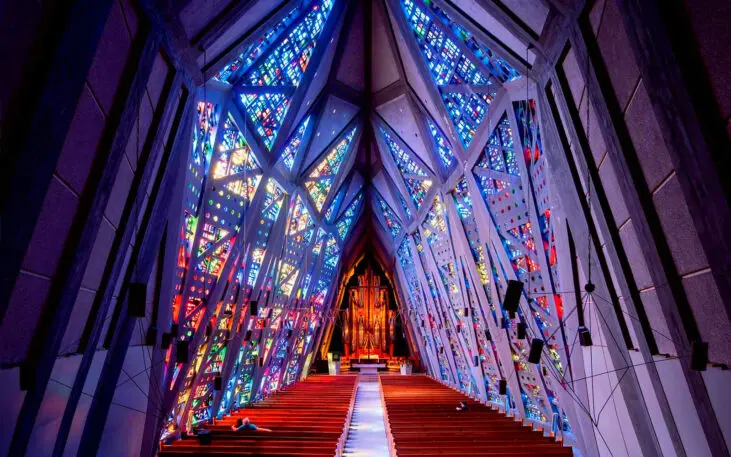

From a flying saucer-shaped concrete memorial in Bulgaria to sphere-topped towers in Kuwait City to a university building with walls of glass in Amsterdam, 13 modernist buildings have just been selected to receive significant conservation grants through the foundation’s Keeping It Modern program.

The buildings were designed through experimental engineering techniques and constructed with unconventional materials that, the Getty notes, “were often untested and have not always performed well over time.” The novel forms and structures require a different type of conservation. Seemingly hard to overlook, these buildings have suffered from neglect or outright abandonment. The Getty’s conservation effort is aimed at slowing the decay and saving these buildings from demolition.

Launched in 2014, the Keeping It Modern program has given grants to conservation efforts for 77 buildings in 40 different countries. This year is the program’s last, and a total of $2.2 million in grants will be distributed to the 13 buildings that made the cut in 2020.

Because these projects used new or little-studied construction and engineering techniques, existing conservation practices aren’t always able to contend with their quirks. The Getty Foundation grants–which have previously gone to projects including the Gateway Arch in St. Louis, the Bauhaus Building in Dessau, Germany, the National Library of Kosovo and the Sydney Opera House–are intended to find new ways of saving their unique qualities.

The end result will be a series of conservation management plans for the preservation and long-term maintenance of these buildings. Some have already been completed, such as the plans for Louis Kahn’s Salk Institute in La Jolla, California and the concrete grandstands of Miami’s waterfront Marine Stadium, designed by Hilario Candela.

The buildings chosen for this program, though, are only a small selection of the world’s endangered modernist architecture. The 13 funded by this year’s grants will now have a stronger chance of surviving, but more than 70 others that applied to the program face an uncertain future.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.