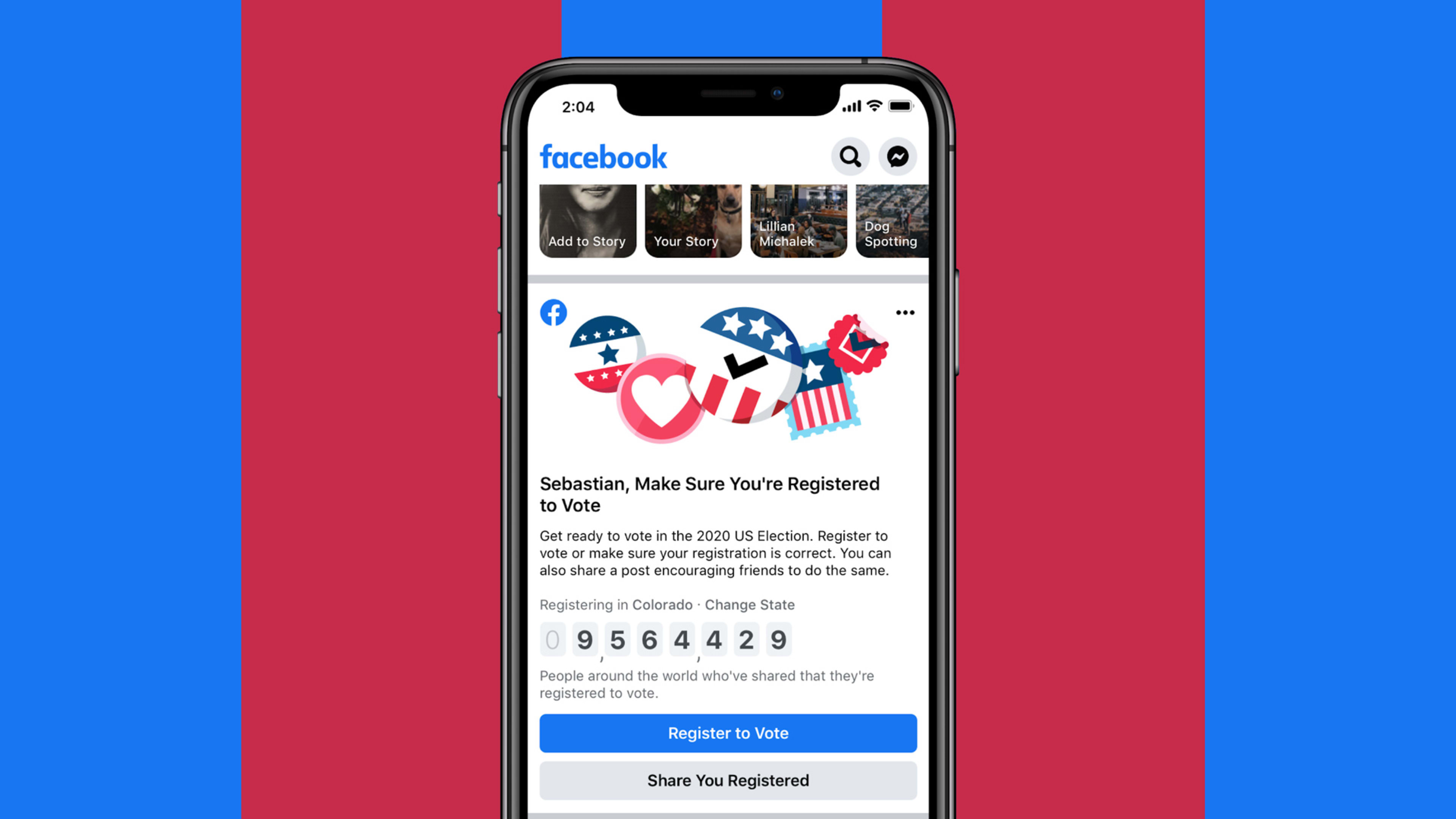

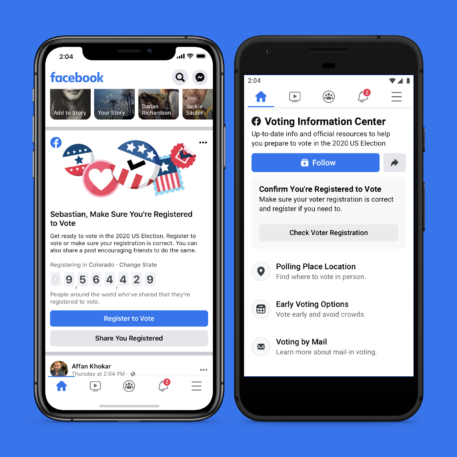

Starting Friday, everyone who’s voting age on Facebook in the U.S. will be part of one of the biggest-ever experiments in democracy: a reminder will appear at the top of their feed with more information about how to register to vote online or in person.

The notice—with a link to your state’s registration website or to a nonpartisan partner if your state doesn’t have voter information readily available online—is part of what the social media giant calls “the largest voting information campaign in American history.” The aim, it says, is to nudge 4 million people to sign up to vote, or “double the 2 million people we helped register in both 2018 and 2016.”

After 2016 and the Cambridge Analytica disaster, Facebook says that it’s waging a ramped-up fight against election interference, giving U.S. users the option to see fewer political ads in their News Feeds, and providing more data about ads to users and outside researchers. But election experts argue that the company’s efforts to encourage voters are simultaneously being undermined by the company’s own hands-off policies toward swarms of inflammatory disinformation, including messages spread by the president.

Micah Sifry, the president of Civic Hall, a New York-based community center for civic tech, who has studied Facebook’s role in elections, said he was reluctant to applaud Facebook’s “ability to turn on a spigot of fresh voter registrations.”

“If Philip Morris put voter registration forms inside of every pack of cigarettes it sells, would we be impressed? Sure, it would probably increase voter registration somewhat, too,” he says. “But that doesn’t alter the fact that what Facebook does to our civic life is mostly toxic.”

Amid a boycott by hundreds of large advertisers, #StopHateforProfit, Facebook said last week that it would take more steps to stem hate speech and to label the president’s misleading or dangerous claims, including warnings on any post that mentions voting. Still, since Trump’s voter fraud claims don’t qualify as “voter suppression” under Facebook’s policies, its efforts are likely to have limited impact on those messages.

“We understand that many of our critics are angry about the inflammatory rhetoric President Trump has posted on our platform and others, and want us to be more aggressive in removing his speech,” Nick Clegg, Facebook’s vice president for global affairs, wrote in a letter to advertisers on Wednesday. “As a former politician myself, I know that the only way to hold the powerful to account is ultimately through the ballot box. That is why we want to use our platform to empower voters to make the ultimate decision themselves, on election day.”

Experiments in nudging voters

Alongside its efforts to stem election meddling, however, Facebook’s voting push raises larger questions about the company’s own electoral influence, both in the U.S. and elsewhere.

Since Facebook first announced its Election Day reminders a decade ago, some have wondered if the messages could be putting a finger on the electoral scales, giving an advantage to whichever party’s constituents happen to use Facebook more, or whichever users happen to see the reminders. Those users have tended to be liberal, an imbalance that could feed into unproven theories that Facebook suppresses conservative viewpoints on its platforms. Antonio García Martínez, a former Facebook project manager, has said that he heard that developers debated whether showing the 2012 voting reminder to iPhone users could unfairly influence the election, since iPhone users also tended to be more liberal.

But Facebook needn’t intentionally tip the scales to impact elections. The company’s voter nudges show us how its policies and algorithms can impact real-world outcomes in subtle ways—and in ways that are still largely a mystery to the public.

The company’s voter nudges show us how platform policies and algorithms can impact real-world outcomes in subtle ways—and in ways that are still largely a mystery to the public.

After the 2016 election, Zuckerberg said it was “pretty crazy” to think that misinformation on Facebook had impacted the electoral outcome. Of course, that kind of influence was part of Facebook’s basic premise: that its platforms can reliably sway audiences—the largest audiences in history—to think or buy what almost any advertiser wants them to, and to keep them coming back for more.

The social media juggernaut has also been impacting voter turnout since its first get-out-the-vote experiments in 2008. On Election Day 2010, as Americans prepared to vote for their congressional candidates, Facebook sent a voting reminder to every U.S. Facebook user over the age of 18, or 61 million U.S. people, a quarter of the U.S. voting population. With researchers from the University of California at San Diego, Facebook examined its data and the election returns. The aim was to learn if the reminder actually worked.

It did. By nudging users with voting notifications and “I Voted” buttons at the top of their News Feeds—including some messages that highlighted users’ friends who had already voted that day—Facebook had built a remarkably effective get-out-the-vote tool. It had created 340,000 additional voters, the researchers reported. If Facebook had shown the Election Day box to every U.S. voter, not just every U.S. Facebook user, more than a million Americans could have been moved to the polls.

“It is possible,” the researchers wrote in Nature in 2012, “that more of the 0.6% growth in turnout between 2006 and 2010 might have been caused by a single message on Facebook.”

The effect was slight but not insignificant: In 2000, George W. Bush beat Al Gore in the decisive state of Florida by 537 votes, or 0.01%. In 2016, Trump’s victory hinged on three states he won by a tiny margin: Michigan (0.2%), Pennsylvania (0.7%), and Wisconsin (0.8%).

The study was one of the largest-ever experiments in the field of social science up until that point, and the first to demonstrate that the online world can affect a significant real-world behavior on a large scale, the researchers said. It was also the first to show how social pressure impacted voter encouragement online: Not surprisingly, a user’s closest Facebook friends exerted the most influence in getting them to the ballot box. (The company’s new U.S. voter registration notification also asks users to “Share you registered” with friends.)

The study, which focused on voter turnout, did not investigate how online nudges can influence how users vote. For social science researchers—at least those who don’t work for Facebook—that question remains an open one, and sits at the heart of debates about the actual impact that Facebook and Instagram posts had on the electorate in 2016.

Two years after the Nature study, Facebook’s influence on users would become the subject of angry protest, after the company published a study on “emotional contagion” that illustrated how the moods of Facebook users could be manipulated. The company apologized for the study, and remained quiet about other experiments until April 2017, when it published more findings in the journal PLOS One.

A voter drive using varying types of messages during the 2012 presidential election had also worked, it said: 270,000 additional votes were cast. For users who got both the reminder as well as notifications from friends who had voted, the uptick in participation was 0.24%.

Which voters get the message, and where?

In recent years, Facebook has quietly expanded its get-out-the-vote efforts to dozens of other countries, too. But as with its U.S. efforts, the company has disclosed few details about the campaigns, or about the impact the notifications have had on voters’ behavior.

Facebook promoted voter campaigns during the Scottish referendum in 2014, the Irish referendum in 2015, and the U.K. election later that year. The company told Das Magazin‘s Hannes Grassegger in 2018 that it ran voter drives in the U.K. during the 2016 European Union referendum and in Germany’s 2017 federal elections. Screenshots Grassegger found online show voter notices in India, Colombia, Holland, Ireland, Hong Kong, and South Africa. Voters have also been reminded about elections in South Korea and Israel, as well as in “endangered democracies” like the Philippines, Hungary, and Turkey.

As in the U.S., Facebook says it aims to show voter notifications to all users of voting age in a given country, but that hasn’t always happened. During Iceland’s 2017 parliamentary elections, Grassegger noted, only some users saw the election day reminder. Facebook said the alert not being shown to every user had to do with users’ individual notification settings or their use of an older version of the Facebook app.

In an email, Facebook spokesperson Kevin McAlister declined to specify where and when it has displayed its voter notifications. “Countries rated free or partly free from Freedom House are eligible to run Election Day reminders, and we determine whether we run Election Day reminders in other countries on a case-by-case basis,” he wrote.

Those decisions may hinge on factors like “electoral violence,” and depend upon the company’s coordination with government officials in each respective country. In some cases, governments have also rejected the election reminders, but Facebook hasn’t identified them.

Alex PadillaFacebook clearly moved the needle in a significant way.”

The precise impact of the drives is also not publicly known, but it appears sizeable. In September 2016, election officials around the country traced a surge in voter registration that month to a 17-word notification Facebook inserted into millions of users’ news feeds.

“Facebook clearly moved the needle in a significant way,” Alex Padilla, California’s secretary of state, told The New York Times at the time. In California, 123,279 people registered to vote or updated their registrations on the day the notice first appeared, the fourth-highest daily total in the history of the state’s online registration site. Minnesota, meanwhile, broke a record for the most online voter registrations in a single week. In nine other states, the nonprofit Center for Election Innovation & Research reported that registration increased from 2- to 23-fold on the first day the reminder went up, compared with the previous day.

The number of registrations was significant, but so too were the types of voters drawn out by Facebook’s effort. Facebook did not disclose demographics or other data from its effort, but the platform has historically been more popular among younger users and women, according to 2019 data from the Pew Research Center, and both groups tend to lean Democratic. “It’s pretty clear that the Facebook reminder campaign disproportionately motivated young people to register,” Padilla told the Times in 2016. Still, Facebook’s users have appeared to skew older in recent years, and data from CrowdTangle show that the majority of the platform’s most shared stories come from right-wing sources.

Ultimately, however, how Facebook has impacted voter turnout, and who benefited most from the additional votes, is impossible to know without more data from Facebook.

How Facebook has impacted voter turnout . . . is impossible to know without more data from Facebook.

The company declined to share details about its research on previous voter encouragement efforts. “I don’t have any other details to share about the reminders,” says Facebook’s McAlister. “I don’t believe there’s more recent research along the lines of the Nature study.”

Still, Facebook’s own researchers are paying close attention to the impact of its voter drives. “We’re planning to use a similar methodology that we used in 2016/2018 to measure registration effect,” he says, without disclosing the methodology.

In the U.S. this year, Facebook says it plans to show its election reminders to as many U.S. users as it can find on its platforms—including Instagram and Messenger—in the months leading up to November.

“I believe Facebook has a responsibility not just to prevent voter suppression—which disproportionately targets people of color—but also to actively support well-informed voter engagement, registration, and turnout,” CEO Mark Zuckerberg wrote in an op-ed last week. But as in previous elections, information about how precisely that works, and who it impacts, will likely remain hidden.

Correction: Facebook has no plans to run voter reminders on WhatsApp. This story has been updated.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.