You know all those studies about brain activity? The ones that reveal thought patterns and feelings as a person performs a task? There’s a problem: The measurement they’re based on is inaccurate, according to a study out of Duke University that is rocking the field.

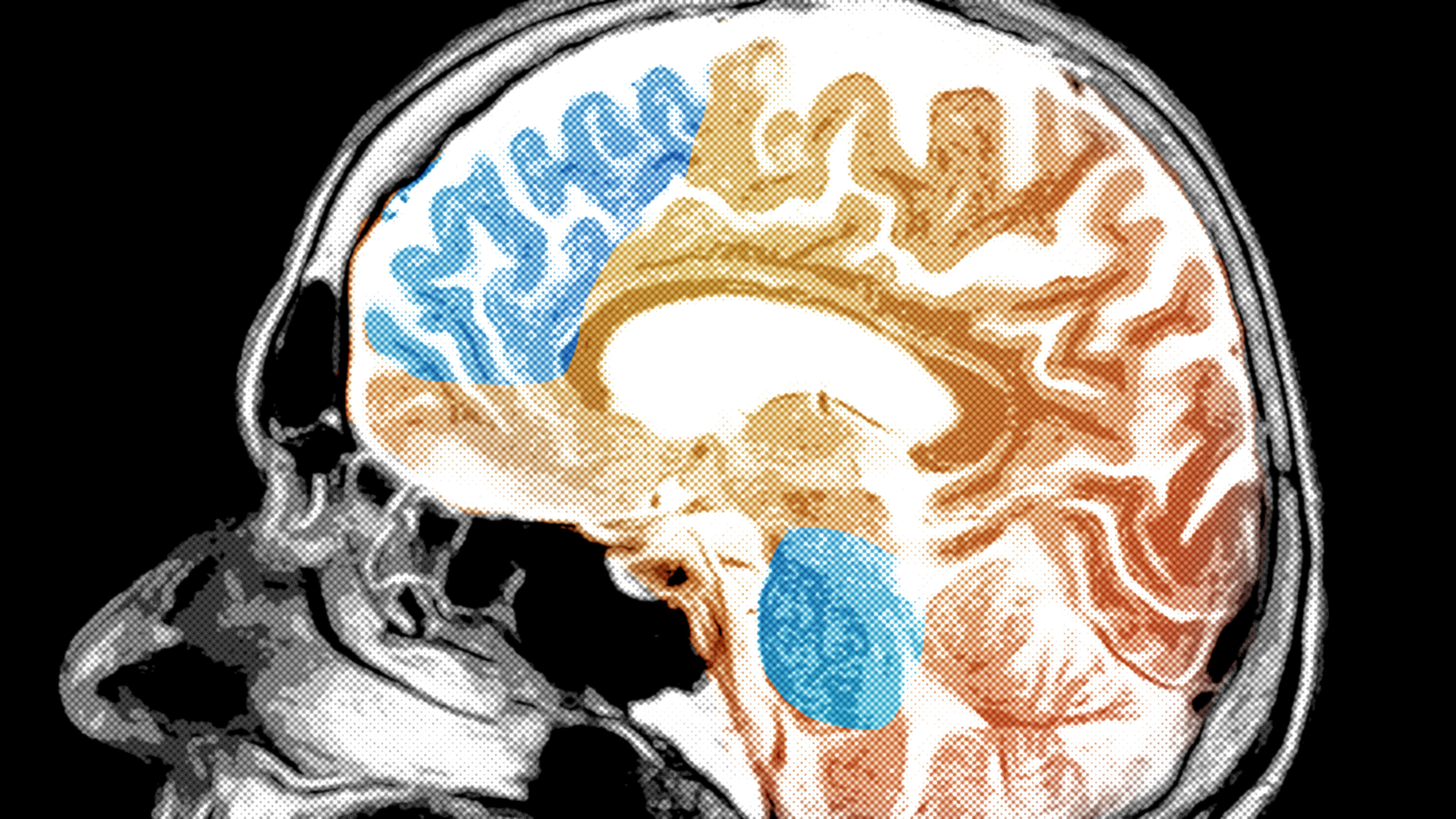

Functional MRI machines (fMRIs) are excellent at determining the brain structures involved in a task. For example, a study asking 50 people to count or remember names while undergoing an fMRI scan would accurately identify which parts of the brain are active during the task.

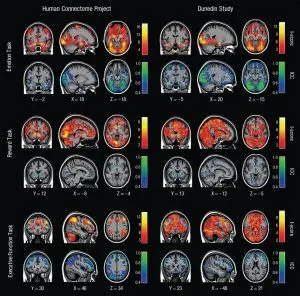

The researchers reexamined 56 peer-reviewed, published papers that conducted 90 fMRI experiments, some by leaders in the field, and also looked at the results of so-called “test/retest” fMRIs, where 65 subjects were asked to do the same tasks months apart. They found that of seven measures of brain function, none had consistent readings.

This is a mouthful of dirt for hundreds of researchers—and Hariri is one of them. He has carried out fMRI research for 15 years, and is currently running a long-term fMRI study of 1,300 Duke students to discern why some come away from traumatic events with PTSD while others do not. “I’m going to throw myself under the bus,” he says. “This whole subbranch of fMRI could go extinct if we don’t address this critical limitation.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.