In 1907, Boston attorney Lawrence Luellen created a cup. It wasn’t made of glass or metal—the norm at the time. Instead, it was made of paper so it could be thrown away after use. While not earth-shattering in our current context, in the early 1900s there were no disposable paper tissues or paper towels. A cup made of paper was a novel idea, one with a noble goal: Luellen hoped his paper cups could help stop the spread of disease.

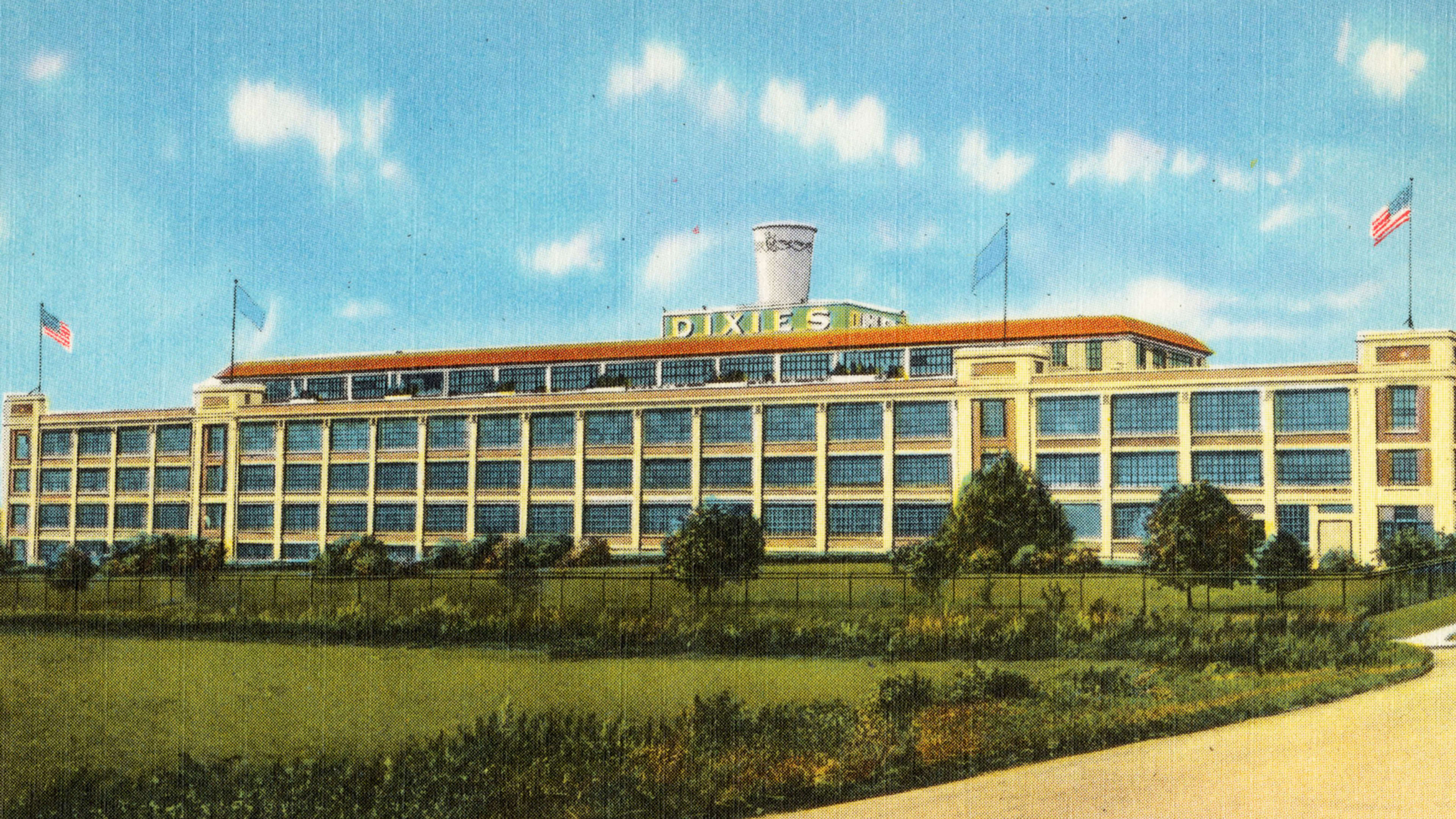

What makes this century-old startup story especially poignant today is that Dixie cups, as they came to be known, achieved only moderate growth for 10 years until the Spanish flu of 1918 made disposable cups a necessity and helped the Dixie cup become a household name. In 2012, Smithsonian Magazine even called the Dixie cup a “life-saving technology” that helped stop the spread of disease.

Before the Spanish flu hit, the company behind Dixie cups was a scrappy startup. But just as we’ve seen with the teleconferencing phenom Zoom in the COVID-19 era, Dixie cups shot to popularity with the arrival of a major health crisis. That’s why the Dixie cup’s story is instructive for startups struggling to make ends meet during the COVID-19 pandemic. Embedded in the history of Dixie cups are important lessons for how startups can scale when times are good—and survive when times are hard.

When timing isn’t right, survive until it is

As any VC will tell you, timing is one of the crucial stars that must align for a startup to succeed. But what if timing isn’t right for a startup?

Chances are, timing won’t be exactly right. To succeed, you must survive until it is.

When Luellen invented the paper cup, which he originally named the “Health Kup,” the timing wasn’t great either. Communal metal drinking cups known as “tin dippers” were commonplace. A single “tin dipper” could be shared by hundreds of different people. If that sounds gross, it was. But scientists were only just beginning to understand how contagion was spread. As a result, when Luellen and his cofounder Hugh Moore went to market with their paper cups, the product didn’t fly off the shelves. It’s hard to sell a solution to a problem people don’t know they have.

Become a B2B or B2BC business

Educating a market takes time and money, two especially scarce resources for a startup. When awareness is the problem, targeting business customers can make the educational process less daunting. While sales cycles might be longer, order sizes are significantly larger and more predictable.

When Dixie cups originally failed to resonate with consumers, Luellen and Moore refocused their efforts on businesses. They developed a free-standing dispenser that was sold to businesses, which could sell a Dixie cup of water for a penny. Once a business bought a dispenser, Luellen and Moore could depend on revenue from the repurchase of cups. This helped the company survive during what was a slow period of adoption. It also introduced Dixie cups to thousands of workers who would soon begin buying them in stores for home use.

Meet the moment

One of the most important skills for any startup is the ability to adapt. As we’ve seen in the most extreme case with COVID-19, factors completely out of a startup’s control can reverse its fortunes, for better or for worse.

Even the lucky ones whose products are perfectly suited for quarantine life have no guarantee that people will take notice. House Party, the group video app launched four years ago, was on its way to becoming a gaming app when COVID-19 hit. It adapted its value prop to meet the moment, launched an advertising campaign—”Be together when you’re not together”—and signed up 50 million users in one month. When current events change the narrative, consider how your company story fits the new reality and make sure people know about it.

“No matter how clean it may look, the soda glass is a common carrier of disease,” one 1920 ad read. “Uncounted lips touch it. Uncounted germs cluster and breed upon its rim—the germs of influenza, pneumonia, diphtheria, and worse.”

As awareness of the health risks grew, more states also banned the use of “tin dippers,” and this made Dixie cups even more popular. COVID-19 may have a similar impact on telehealth startups. Already payers have significantly expanded coverage for telemedicine, HIPAA requirements have been relaxed, and some states have lifted state licensure requirements.

Evolve your message

One lingering question is if those startups made essential during the pandemic will keep growing once the pandemic passes. If remote work and telehealth become as widespread as some people think, those startups will see increased competition and pressure to differentiate beyond what set them apart originally.

That’s what happened to Dixie cups. As the popularity of disposable cups grew, copycats entered the market, leading Dixie cups to find novel applications, such as “Ice Cream Dixies,” a frozen treat that soda fountains used to offer. The company also began touting other benefits beyond disease prevention, such as convenience.

Feeding the innovation loop

With the success of Dixie cups came other disposable products, such as Kleenex in 1924 and paper towels in 1931. This also led to new and environmentally harmful materials such as polystyrene finding their way into consumer products.

As the history of Dixie cups shows, a product that solves one problem can create new ones. Some people are already complaining of “Zoom fatigue,” for example. Products that become popular during the current pandemic will have their own first- and second-order effects. Some of the problematic ones will present opportunities for intrepid new startups.

Kevin Leland is CEO of Halo, an open innovation network where companies connect with scientists and startups to solve important business challenges.

Recognize your brand's excellence by applying to this year's Brands That Matters Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.