Earlier this week, Uber acquired Postmates, the number-four player in the food delivery space, for $2.65 billion. It was a clear statement that Uber is no longer just a rides company, but a home delivery company. Now, Uber is rolling out a new design in its main app that gives its Uber Eats business equal real estate with rides on the app’s home screen.

This shift in Uber’s business began last year, but was dramatically accelerated by the coronavirus pandemic. As people began sheltering in place, the company’s rides business fell by 80% in April, and Uber Eats, the restaurant food delivery business, suddenly became its most popular product. Now, Uber Eats’s success has established it as a model from which Uber can design other services that rely on its advanced logistics platform.

“We’ve really doubled down on our Eats business, extending not just in food, but from food into adjacent categories like delivery, like grocery, and essentials,” says Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi in an exclusive interview. “There we’re seeing a pretty extraordinary acceleration, which is good for the business, but it’s also a really important lifeline for the restaurants and other local stores in every city, that frankly our customers are interested in keeping alive in an unbelievably difficult situation [with] COVID.”

Uber’s new focus on Eats may help it survive the pandemic, in which the company has already shed a quarter of its 26,000-odd person global workforce in two rounds of layoffs. But it’s unclear whether Eats and other new Uber services can speed the company’s path toward profitability. Uber has lost a lot of money since its ill-fated IPO last year: It reported a $8.5 billion loss for full-year 2019. It reported a net loss of $2.9 billion in the first quarter of 2020, its biggest loss in three quarters. Before the pandemic hit, Uber said it expected to hit profitability in the last quarter of 2020, but was forced to withdraw that guidance in April, saying the coronavirus had made its 2020 financial performance “impossible to predict.”

By stretching its platform and riffing on its core model, Uber is aiming to find new revenue from existing and new customers—as well as, Khosrowshahi hopes, a faster path toward profit. This isn’t a new idea at Uber (remember “Uber Everything“?). What’s different is the sense of urgency brought by coronavirus, the rapid maturation of the home delivery space, and the pressure on Uber to hold its own against rivals hungry to capture new demand. This shift is reflected in the refreshed design of the Uber app, which begins rolling out today in various parts of the U.S.

“We wanted to make sure that when cities open up, Uber opens up as well, [that] we’re part of the heartbeat of every single city,” Khosrowshahi says.

Uber’s new face

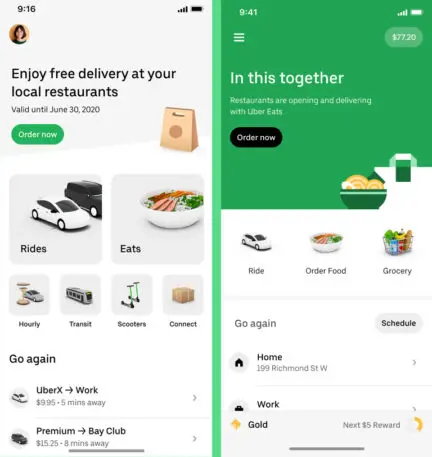

The Uber app’s general look hasn’t changed that much over the years. When you open it, you expect to see the familiar map and little car icons moving around. But as Uber’s business evolves amid the challenges of the pandemic, the app needed a refresh to reflect the company’s direction.

Now, the first thing you might notice when you open the Uber app is the introduction of food delivery as an equal theme in the design, something Uber has been experimenting with since last year. But the pandemic pushed the company to fully commit to making the Uber app about more than just rides.

“I still remember the week we decided to do this. It was crazy,” says Peter Deng, Uber’s global head of rider products. “The [product manager] on the team responsible for the home screen experience got on a one-on-one and said, ‘Hey, given where we are, have we considered just changing our app to be all about Eats and just drastically changing it?'”

After that initial conversation, Deng says they then took the idea to Khosrowshahi. “That conversation lasted no more than 30 seconds—it was a no-brainer,” he says. “It was like, ‘This is what we’ve got to do.'”

When you first open the app, you’ll see a group of buttons representing various services, including two large buttons that lead to Uber’s two main services, Eats and Rides. Below those you’ll find a row of four smaller shortcuts that will link to newer Uber services, some of which are based on the Uber Eats model.

[Animation: courtesy of Uber]As Daniel Danker, who heads up the Eats and Delivery product teams, explained to me, the company’s services now focus on two basic scenarios—one where Uber helps you go somewhere (via an Uber driver’s car, a scooter, or a bike), and another where you get something (such as a meal from a local restaurant).

On the “go” side, Uber plans to offer the service of a driver and car for increments of time, instead of single trips. But most of the new services focus on “get” scenarios that leverage the Uber Eats model and where Uber drivers act as couriers. For example, you can order up an Uber courier to pick up something and deliver it to a friend across town using the Connect service. Uber plans to increasingly deliver things to you from local businesses, such as pharmacy products, home goods, or flowers, via its Direct service. And you’ll see Uber competing with Amazon and Instacart in grocery delivery.

Dara KhosrowshahiWe think we can really extend the definition of movement from moving you from point A to B, to moving . . . anything you want to have delivered to you.”

What Uber really wants is for you to get so accustomed to using a number of these services that cracking open the Uber app becomes an everyday thing, not just a once or twice a week occurrence when you need a ride.

“Over a period of time, we think that we can shift behavior from one mode of behavior into multiple modes of behavior,” Khosrowshahi says of the new app experience. “And just as Amazon went from books to overall retail and opened up their marketplaces to third parties, we think we can really extend the definition of movement from moving you from point A to B, to moving . . . anything you want to have delivered to you.”

Eats and beyond

However, Khosrowshahi says Uber’s biggest challenge is convincing people to try newer services like Uber Eats for the first time—something the new design is supposed to encourage.

“And once they try them, they love them,” Khosrowshahi says. “I mean, the magic of pushing a button and taking a ride is a spectacular experience. The magic of pushing a button and having hot quality food from a local restaurant show up, it’s a magical moment. And frankly, once you’ve experienced it, you want it again and again and again.”

That magic—plus the need to get food without leaving home—caused many people to try Uber Eats during the pandemic. Khosrowshahi told analysts Monday that Eats had “record volumes and strong growth” throughout April, May, and June, with bookings during that period expected to grow 100% compared to last year’s second quarter. The business isn’t yet profitable, in part because the company is subsidizing each food delivery in an effort to get traction against rivals such as Grubhub and Doordash, which offer very similar services.

Restaurants have some very good reasons for hooking up with Uber Eats, too.

Before the pandemic, many restaurants in the U.S. weren’t in a great hurry to do online delivery, and for the ones that did, it represented only a small percentage of their business, says Janelle Sallenave, who leads Uber Eats’s North American business.

Janelle SallenaveOvernight, during shelter-in-place, it had to flip, it had to become the majority part of their business.”

“And overnight, during shelter-in-place, it had to flip, it had to become the majority part of their business,” Sallenave tells me. “So what we saw in March were restaurants either moving into the category of online food service or wanting to be on every platform possible.” For a month after the lockdown orders began, Uber scrambled to onboard nearly twice the normal number of restaurants wanting to open virtual storefronts on Uber Eats, she says.

For Uber Eats, Uber integrates with a restaurant’s point-of-sale system, and when the food is ready, an Uber driver delivers it. Grubhub and Doordash also integrate with restaurant systems.

Because restaurateurs wanted to meet customers in their own ways, they began asking for variations on the Uber Eats model. Uber obliged. For some restaurants, Uber now extends just the logistics function of the platform. Sweetgreen, for example, invites people to buy their salad from its own app, but the order is delivered by Uber. In other cases, restaurants use the Uber Eats app as a marketing front end. They take food orders through an Uber Eats storefront, but then have their own people do the delivery.

Uber wouldn’t share how many users Uber Eats has, but it does claim that Uber Eats is the most downloaded food and drink app in the world.

Getting into grocery delivery

By providing different services that accommodate restaurants’ needs, Uber has also been able to expand to new services. First among them is grocery delivery, which originally came to life as an outgrowth of Uber Eats. Long before the virus, small markets and convenience shops began to set up storefronts within the Uber Eats app, and people were using them to order things like eggs and cheese, says Liz Meyerdirk, who leads the global business development team for Uber Eats and Delivery.

When the pandemic hit, this began happening more often. The coronavirus had suddenly made grocery delivery a regular, must-have service for millions sheltering in place. Uber says that during the pandemic it saw an increase of 117% in grocery bookings revenue compared to the same period a year ago, and a 34% increase in the number of Uber Eats storefronts set up by grocers.

Now, grocery delivery is about to emerge from the shadows of Uber Eats and become a more formalized service offering, says Daniel Danker. Uber has already done much of the groundwork. It acquired the grocery delivery platform Cornershop last year and is now integrating that technology with the Uber Eats platform in Canada and Latin America, where Cornershop is active. Later this summer, Uber expects to launch its grocery delivery service in the U.S., starting with Miami and Dallas.

Danker says Uber will compete with the other players in the market, like Amazon and Instacart, by offering grocers access to a larger number of consumers who are already accustomed to ordering services through Uber’s app. It’ll also provide grocers with richer analytics data from their sales on the platform.

Consumers might come to prefer the Uber grocery experience if it can make grocery buying more like calling for a car, Danker says. Amazon requires you to pick (and sometimes pay for) a delivery time, Danker points out, so it’s not a true “on demand” service.

“If we could turn that into an on-demand experience where you could just place your order and within a few minutes you’d know that it was coming, that’s going to liberate you and make it that much more of a simple, delightful experience,” Danker says.

Getting to know you

You might start your grocery order by tapping one of the Uber app’s new shortcuts. And in the interest of making the experience even more seamless, the app will very likely keep track of the grocery items you typically order, as well as when and how often you order groceries.

Uber believes that understanding and anticipating its customers’ needs—via its considerable data science chops and stores of customer data—may become an increasingly big draw for its app. By knowing a lot about when and where and how people get things done, the app will be able to suggest those things and make them easy to order up when the time is right.

Daniel DankerThat’s going to liberate you and make it that much more of a simple, delightful experience.”

That includes the hits, like Rides and Eats, but also new services like Connect, Uber’s consumer-to-consumer delivery service for packages that weigh less than 30 pounds and are worth less than $100. Uber began offering the Connect service in mid-April, in the middle of the pandemic, and now it’s available in 140 cities. “We built this whole thing in about two weeks,” Peter Deng tells me. “This is what my team does—we look at what would be really helpful for customers and how quickly we can get that service out there.”

“Hourly” will also soon be a fixture on the Uber app’s home screen. This service, which is already available in 50 cities, lets you hire a car and a driver for a period of time, perhaps to run a series of errands. The service lets you stick with the same driver without having to call a new one for every errand. This not only answers a pre-COVID-19 desire among passengers, but it also greatly reduces the number of contacts between drivers and customers amid the current threat of a dangerous contagion. Twenty more cities will get the Hourly service in July, Deng says.

By putting a variety of new services front and center and intelligently surfacing the one you’ll likely need, Uber hopes to become an everyday necessity—and a profitable company. But the company’s fiscal fate also depends on several unknowns, like whether Uber Eats continues growing after the pandemic and how much longer Uber has to subsidize food orders to convince people to try the service. As critics have pointed out, food delivery isn’t an easy way to make money, and some equities analysts remain skeptical that Eats will ever be a core business for Uber.

Wall Street seems to believe that Uber’s value is based on how quickly the world reopens after the pandemic, and how soon people begin ordering rides again. That’s understandable: In the last quarter of 2019, before the pandemic hit, the rides business contributed three-quarters of Uber’s revenue. But as the company’s home delivery services mature—Eats being just one of them—it will become more apparent that Uber is intent on evolving its platform far beyond rides. And its app will provide an ongoing window into that process.

“You’re going to look back on screenshots of the old Uber app five years from now,” Deng says, “and say, ‘Wow what was that? That was a very different company and a very different app than the one I know.'”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.