With protests in full swing and many parts of the country open again, it’s easy to forget that COVID-19 is still lurking and anticipated to take an additional 100,000 American lives by October. Scientists now concur that COVID-19 spreads primarily in droplets through the air—be it from coughing or just talking—so public health officials recommend that people wear masks and face shields, and maintain social distancing of at least 6 feet. But many researchers believe that these guidelines don’t go far enough. To truly help protect people from transmitting COVID-19, we need to fix the air we breathe.

Over the past months, Fast Company has connected with many experts on the topic of air quality and circulation. They’ve offered a variety of best practices for everyone, from restaurant owners to CEOs to families, to consider. Here’s what we’ve learned so far.

Social distancing isn’t necessarily enough

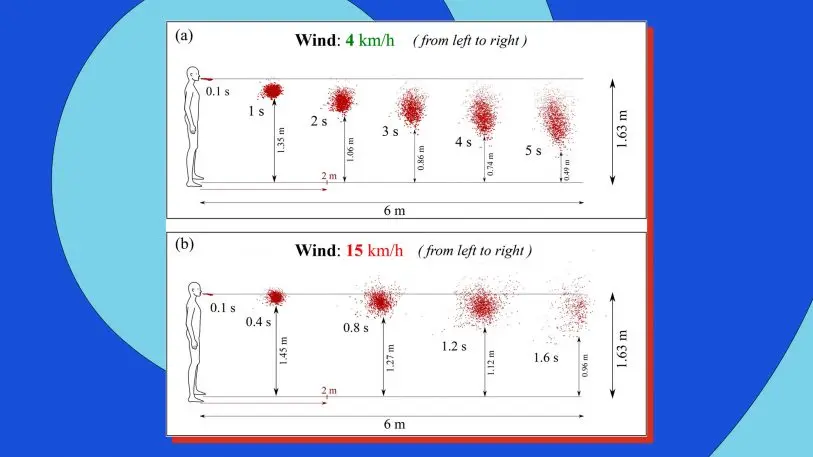

We’ve heard it again and again that 6 feet of social distance creates a safe buffer, and restaurants, offices, and even Starbucks cafes are being redesigned around that tenet. Social distance does help prevent transmission, but according to new modeling, even a small breeze can spread COVID-19 up to 20 feet.

Dimitris Drikakis, the professor at University of Nicosia, Cyprus, who created the model, insists that this finding doesn’t mean that someone coughing 20 feet away will get you instantly sick. The overall amount of virus you breathe in over time matters, too. But his research does confirm that even outdoors, distance gatherings come with some risk. And given these findings, we should scrutinize our indoor air aggressively, too.

Add filters and usher fresh air indoors

Something experts in air quality talk about a lot is how many liters of air a person is getting per minute. Whether that’s inside a cruise ship or a building, a portion of that air might be fresh air pumped in from outside, and a portion will be recirculated (and hopefully, filtered).

According to Qingyan Chen, professor of mechanical engineering at Purdue University, planes are pretty good about providing clean air to passengers, because floor vents suck air away from passengers, and through HEPA filters you don’t see, before pumping it back through the cabin. This system is by no means perfect, but HEPA filters capture 99% or more of viruses that are .3 microns or larger.

On cruise ships and in many buildings, HVAC systems use lower-quality air filters, which might catch just 20% to 40% of viruses passing through. On the tragic Diamond Princess cruise ship, which quarantined thousands of passengers to their rooms for nearly a month while the ship was dry-docked in Tokyo Bay, air circulated between cabins without HEPA filtering. Chen, who has consulted for the cruise ship industry since the disaster, believes this strategy infected as many as 700 people and killed 8 people who were breathing the same old stew of air, though one paper has since challenged that conclusion.

In our reporting from architects and office specialists, we’ve heard that U.S. office buildings may begin to retrofit with higher-end HVAC systems (with HEPA filters and even UV light sterilization hiding in the ducts), which are more common in China, but it’s hard to quantify how many companies and landlords are actually taking those steps.

The safest option for quarantining viruses in the air are negative pressure rooms, which operate like vacuum cleaners, ensuring that no pathogens can escape. But they’re designed for hospitals. They’re not feasible for hotels, offices, and other buildings for a variety of reasons—including expense, the difficulty in validating their design, and the fact that every office worker in America would need their own office with a door that is always closed. Only 2% to 4% of all hospital rooms are equipped to be negative pressure spaces as it is.

Humidity is important

Some scientists believe that summer could help curtail the spread of COVID-19 due to heat. Indeed, researchers have shown that extreme heat can kill the virus; Ford even retrofitted police cruisers to sterilize car cabins with nothing but the hot air blowing in from the engine.

One component of air quality that hasn’t gotten as much attention is humidity. Stephanie Taylor, infection control consultant at Harvard Medical School, is petitioning alongside companies that make sensors and humidifiers to improve air quality, for the CDC and WHO to adopt guidelines around safe humidity levels—specifically that indoor humidity should be kept between 40% to 60% (the current recommendation of the EPA). That’s the range of what most people consider comfortable humidity indoors, with air that won’t dry out your nose. (By comparison, the Mohave Desert ranges from 10% to 30% humidity.)

[Source Image: peterspiro/iStock]Taylor’s own interest in humidity began in 2013 when she was studying (PDF) how infections spread at a new hospital. Her research isolated just about every aspect of a hospital you could imagine, and she discovered a link between infection rates and humidity in patient rooms. In fact, it was the single biggest correlation she found. “I was totally blown away,” Taylor says. “And to tell you the truth, I was skeptical.”

But Taylor has since validated these findings on studies at nursing homes (PDF) and schools. And from her research and others in the industry, she identifies three ways that midrange humidity levels stop the spread of airborne pathogens. First, when air is too dry, large droplets don’t fall to the ground as quickly as they normally would. Instead, they dry out to become smaller droplets, which float in the air longer (and also take longer to drop to surfaces, meaning the surfaces can continue to be contaminated). Secondly, airborne viruses that thrive in winter, like coronaviruses, simply aren’t as infectious when they float through moister air—whatever tools the viruses use to be virulent are somehow stunted. “There are a few theories as to why,” says Taylor. “But to tell you the truth, I don’t think we fully understand the mechanism.”

The final reason is that your respiratory immune system just works better in greater humidity. Recent research out of Yale exposed mice to a strain of influenza. The mice were kept in the same air temperature, but researchers tweaked the humidity levels. They found that mice in low-humidity chambers had a worse immune response. Humidity didn’t actually remove the influenza droplets from the air; instead, the air moisture helped their bodies fight off the virus better—all the way down to the cellular level in their respiratory system.

Distancing. Filtering. Humidity. None of these individual solutions can prevent the spread of COVID-19. But used in combination, we can make our indoor air safer—to make it through this pandemic, sure, but also cold and flu season, and whatever pandemic awaits us in the future.

“This type of infectious disease will come every few years,” warned Chen, the Purdue engineer, back in March. “I started doing research when SARS broke out in 2004. Then another time was the 2009 influenza from Mexico, which killed 150,000 people around the globe. Today we have coronavirus. Every couple of years, this type of thing will come back.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.