Over the last few weeks, as protestors have taken to the streets to advocate for racial justice, brands have felt compelled to be part of the conversation. It hasn’t always gone smoothly.

In many cases, people have pointed to the hypocrisy of the bland Instagram statements, questioning the makeup of their executive teams or their efforts during the rest of the year. When Book of the Month published a post encouraging followers to “Read Black authors,” many asked why the club itself hasn’t featured many black authors.

In other cases, employees have offered detailed accounts of the racism and discrimination they say they experienced working at those brands. Gabriella Sanchez, who worked at Bando for two years, described how founder Jen Gotch took employees to lunch and spoke in what Gotch herself described as a “plantation accent.”

https://www.instagram.com/p/CBEH4ICjAIu/

Now, companies are trotting out apologies: Among them, the founders of Reformation, Dollskill, Refinery29, and Bando, who have all acknowledged that they’ve messed up in the past and pledged to do better. (The latter two have said they will step down from top roles at their companies.)

https://www.instagram.com/p/CBLToSInUcb/

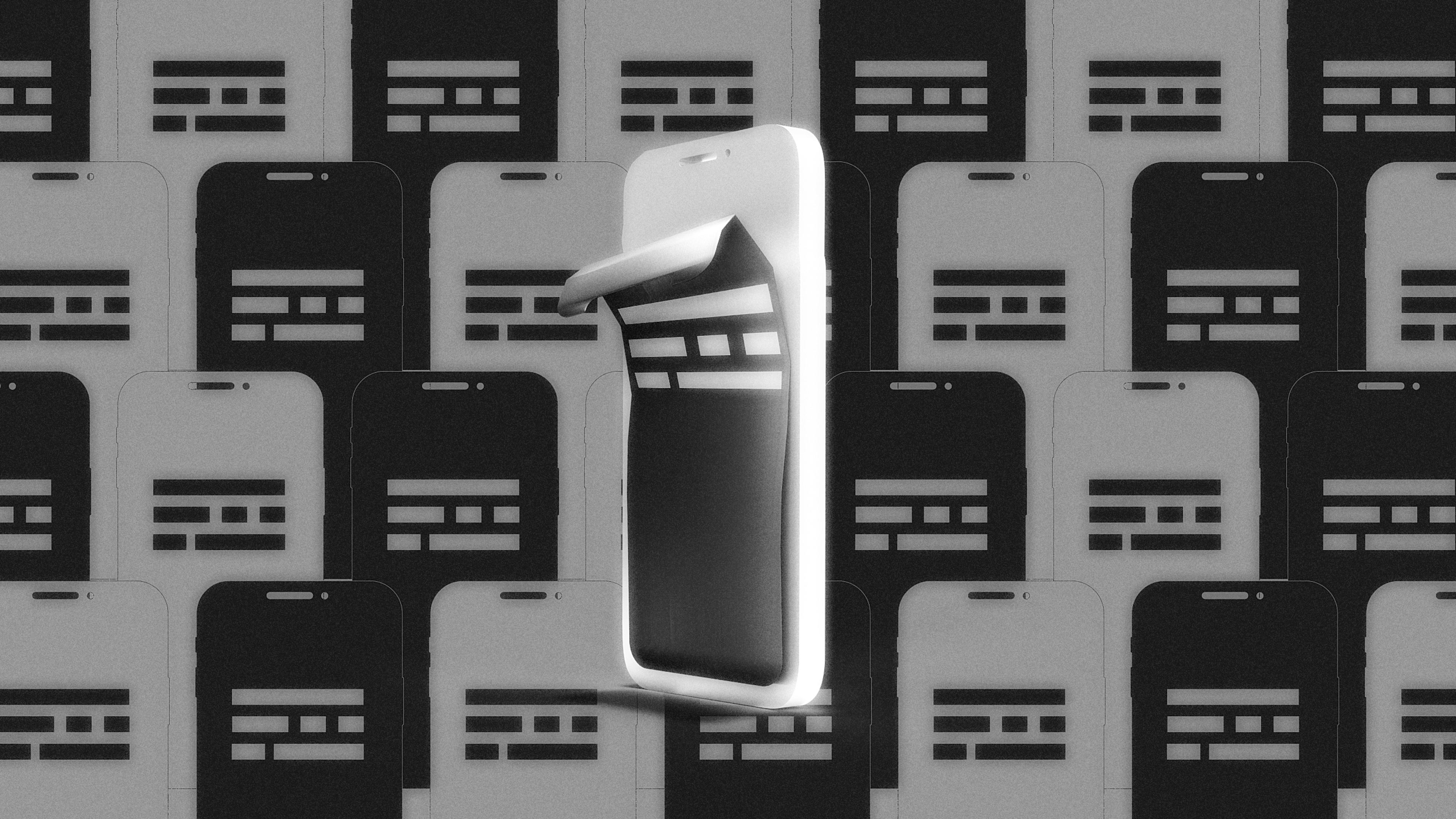

These apologies are popping up every day, and the visual language is so similar, it’s starting to look formulaic. Many choose to voice their remorse and contrition through words on Instagram, without any images. Instead, there are lengthy written statements that often take up many slides, describing all the ways the brand or founder has failed, and all the ways they’re planning to do penance, including making donations and diversifying their teams. Posts on founders’ personal accounts are no less bland and impersonal than those on the corporate accounts.

These posts appear to be trying to make a visual impact through minimalism and simplicity, contrasting the color of the words against the background. But given that they’re all starting to blend together, it’s unclear how effective this approach is. “It all falls really flat,” says Bobby Martin, founding partner of Champions Design, a branding and design agency. “From a design perspective, a quote can feel very removed from humanity. I want to see a person’s face: I want to look into their eyes and see that they actually mean it.”

https://www.instagram.com/p/CA6u5yrp_tp/

Martin points out that this approach of printing a few works against a white or black background has been common over the past few months, as brands have tried to respond to the COVID-19 crisis. Brands communicated with their customers in a similar way, describing their response to the crisis with a few words against a simple background. “We were bombarded with brands thanking healthcare workers and saying that we’re ‘in this together,'” he says. “This has rolled right into what we’re experiencing now with the protests. ”

The problem with this approach, Martin believes, is that it’s too safe. Reformation CEO Yael Aflalo, for instance, came under fire for declining to include a black model in a shoot, saying, “We’re not ready for that yet.” In her apology, she acknowledged that she had “failed.” But it didn’t communicate any real vulnerability. This and other corporate apologies make it seem like the companies are simply going through the motions and caving to public pressure to speak up. None of this inspires confidence that the company is on track to create real change by hiring more black people and grooming them to become leaders. “They can’t make the world better if they don’t hire better,” Martin says.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CBJ1RFAnthN/

And perhaps most importantly, it’s worth asking, as writer Helen Donahue did on Twitter, which graphic designers have been asked to design apologies but keep them “on brand”? According to the 2019 Design Census, only 3% of designers are black. Martin makes the case that part of the reason this communication about Black Lives Matter, and the ensuing apologies, feels so flat and inauthentic is that there are so few black designers contributing to the conversation. “If black designers were part of the process, it would be a much richer message,” says Martin. “There would be more vulnerability and more action that would come out of it.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.