As protests have taken over the U.S., police officers in Minneapolis, Los Angeles, Sacramento, Kansas City, Chicago, and more have opened fire on crowds—bruising, maiming, and even permanently blinding peaceful demonstrators and members of the press. The shots fired have primarily been with what are colloquially called rubber bullets.

The name is a bit of a misnomer. These kinetic energy (KE) rounds are rarely made of rubber these days, and some even have metal components, just like conventional bullets. Most are actually shot from grenade launchers, though shotgun rounds are also popular, and rounds are even made for rifles and pistols. Instead of piercing the skin, the rounds are meant to strike someone with blunt force, incapacitating them like the swing of a baton but from afar.

More than a century in the making, rubber bullets can cause serious injury, and even kill, and it’s taken time for the semantics to catch up. Once called nonlethal weapons, research has demonstrated their dangers, like that up to 15% of people struck with KE rounds are left with a permanent disability. They were renamed “less-than-lethal” for a while in the early aughts, and now much of the world, including the UN, calls them by a more suitable title: “less lethal” rounds.

“Very few still use the term ‘nonlethal.’ Nonlethal is a particularly American thing, I guess,” says a ballistics researcher from the U.K. speaking under the condition of anonymity. “And it’s stuck in U.S. law enforcement, perhaps because they like the way it sounds.”

While manufacturers have stringent agreements around the specifications of lethal ammo, less-lethal ammunition is a $1 billion industry with zero federal oversight and no industry groups providing independent auditing or testing of the ammunition. That may soon change, but for now, it’s a Wild West of technology inside an inherently opaque industry. I reached out to half a dozen less-lethal ammunition manufacturers for this story, and none of them responded to my request for an interview.

But in talking to top experts across the industry, a few things are clear about less-lethal ammunition: It’s wildly unpredictable when used in real world conditions. It can kill and maim a person. And it should never be used on peaceful protesters. Even though, for the last 100-plus years, it has been, as the whitewashed tool of authoritarian governments. Where protests have started, less-lethal ammunition follows.

The origins of rubber bullets

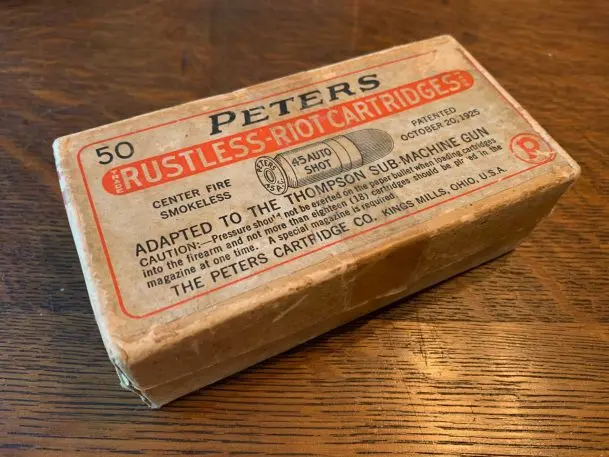

The history of KE ammunition, also called kinetic impact projectiles (or KIPs) is tricky to pin down at best, but we do know they didn’t start as rubber bullets; they began as wooden ones. By one commonly cited claim with murky origins, wooden bullets originated in Singapore in the 1880s, as police officers loaded sawed-off broom handles into their guns instead of normal rounds, firing them at rioters to presumably injure them without the threat of death.

“Law enforcement liked the Thompson SMG for the same reason that criminals did, and I suspect that the development of this particular round allowed the police to fire a huge ‘spray’ of nonlethal birdshot in a very short period of time,” Helms says. “If one was trying to push back an angry mob, that would be a pretty effective way of doing it.”

Helms postulates that less-lethal rounds became popularized alongside the increasingly well-funded and violent U.S. police forces around the turn of the twentieth century, and points out that it’s probably not a coincidence that riot control rounds may have appeared when the populace was angry, Prohibition was at its peak, and organized protests were common.

By the 1960s, colonial British forces began firing wooden “baton rounds” in Hong Kong, likely to impose power over the growing wave of strikes, protests, riots, and other demonstrations in support of communist China. These rounds were made of teak wood, which is one of the hardest types of wood. The name “baton rounds” came from their goal, to duplicate the impact of a baton on human flesh from a distance.

Then in the 1970s, the British Army brought a new type of ammo to Northern Ireland. This one was a long, hard rubber projectile called the L2A2—the first “rubber bullet.” Developed over nine months, it was a 6-inch round that looked like a small missile, designed to shut down protesters at a range that exceeded rocks they might throw. Fifty-five thousand of these rubber rounds were fired over the course of four years. It was also the first instance in which the negative impacts of less-lethal ammunition was scrutinized; not only were the rounds dangerous on impact, but they were notorious for skip firing, or bouncing to ricochet and hurt others. Around this era, we see more experimentation, including the rise of bean bag rounds, and the British Army began reformulating its bullets to plastic.

“We like what we see,” said Sgt. H. G. Dublin at the time. “It gives us a new option in crowd dispersal.”

Then in 1995, the Department of Defense upped the ante. Following the withdrawal of ground forces in Somalia, the Army and Marines teamed up to launch the Joint Non-Lethal Weapons Directorate. This program developed new “nonlethal” weapons. The most popular result was developed by army officer David Lyon, called the Sponge Grenade. It looks almost like a NERF toy, or a big foam pencil eraser with a rubber bottom. But looks can be deceiving. It hides a stiff metal core, and it’s shot from a grenade launcher to immobilize targets (and in some cases, it’s killed these people).

The Army licensed the sponge grenade to the private industry, and now this military technology is sold to police officers nationwide as part of a much larger trend in which cops use military-grade armor and weaponry. According to one expert I spoke to, it is the most popular piece of less-lethal ammunition used in the U.S. today, even though quality and reliability has been proven to vary by manufacturer. Lyon and the Army declined comment about the intent, development, and licensing of the munition.

A 2017 report that analyzed the impact of rubber bullets between 1990 and 2017 found that 3% of people struck died, and three out of four people struck were left with severe injuries.

The challenge of designing a bullet not to kill

Ask any expert in the industry what less-lethal ammunition needs to do, and there are two criteria it has to meet to be remotely safe: It needs to be accurate, and it needs to hit its target with the right amount of force for the right amount of time to incapacitate but not injure them.

The problem with designing nonlethal bullets to meet these criteria is that, foundationally, they don’t follow the normal rules of bullets that make lethal rounds work so predictably.

Inside the barrel of any pistol or rifle is what’s called “rifling.” Rifling is a series of grooves in the barrel that put a spin on the bullet as it leaves the gun, ensuring it cuts accurately through the air like a tight spiral thrown by a football quarterback. But the grenade launchers and shotguns used for the majority of less-lethal munitions have no rifling grooves inside the barrel, meaning that KE rounds can flip erratically through the air, looking more like a punt than a pass. The problem is only compounded by the slow speed of the projectile. Lethal bullets are small and fast, firing at 1,000 feet per second, which lets rifles hit their targets from a mile away. Less-lethal bullets are larger and less aerodynamic. Loaded with less gunpowder, they fire at roughly ⅓ the speed of a normal bullet, meant to hit the target slow but hard.

I just got hit by a rubber bullet near the bottom of my throat. I had just interviewed a man with my phone at 3rd and Pine and a police officer aimed and shot me in the throat, I saw the bullet bounce onto the street @LAist @kpcc OK, that’s one way to stop me, for a while pic.twitter.com/9C2u5KmscG

— Adolfo Guzman-Lopez (@AGuzmanLopez) June 1, 2020

With erratic flight, you have two problems. First, the bullet could hit anywhere on the target’s body (it could also hit anyone standing near the intended target, anywhere on their body). Whereas the torso and legs are considered the safest areas to strike, bullets that fly up toward the neck or face can easily kill.

Michele Heisler is the medical director of Physicians for Human Rights and a professor of internal medicine and public health at the University of Michigan. She has been on the ground in Turkey to examine people who have been shot with less-lethal munitions. Heisler calls these scenes “horrific.” She has seen how even well-placed, perfectly executed shots still cause blunt trauma, which can do more than bruise or even break a bone: She’s witnessed these rounds do internal damage to organs like the lungs and heart and injure nerve bundles in limbs, necessitating amputation.

“I don’t know why, they do seem to directly hit people’s eyes [a lot]. It hits your eye and ruptures the eyeball, or the globe . . . basically, your eyeball explodes,” she says. But the terrifying truth is that someone losing their sight to a less-lethal round may have actually gotten lucky. “The eye is a very open entry point to the brain,” she adds, which is a primary route for these less-lethal rounds to kill.

Building standards

Twenty years ago, Cynthia Bir was a young grad student at Wayne State, searching for her dissertation topic. Located in Detroit near GM, the university helped the company develop the first crash test dummies, which are full of intricate sensors to simulate a crash’s impact on the human body. A kinetic energy round manufacturer reached out to Bir’s mentor who worked at GM, curious if they could help validate the performance of their rounds. Bir retrofitted the dummy to be shot with less-lethal rounds, measuring the impact.

Today, she’s a professor and chair of biomedical engineering at the university, and one of the world’s leading scientists studying kinetic energy rounds. Bir has received funding from manufacturers to validate the performance of their products. Her current lab rig consists of two tests. One part is a dummy torso that she developed from her dissertation research (with no head or limbs), which measures the impact of a round on the chest. The other part is what’s called a “skin surrogate,” which simulates the impact on the layers of skin tissue. This surrogate is actually a ballistic gelatin that’s covered with chamois.

As Bir explains, there are no set standards for KE munitions in the U.S. or internationally. Manufacturers don’t have minimum performance goals set by any trade organization or larger governing body, either voluntarily or by law, which would ensure a baseline of safety or oversight in the industry. But Bir has been involved with two groups that may change this within the next year or two.

In the U.S., she’s been leading the creation of a KE round safety standard for the ASTM (the American Society for Testing and Materials), which is already used to certify bike helmets and police armor. It’s not a legal mandate, but a set of specifications that a manufacturer can reach to be ASTM certified. In theory, such standards can help weed out the worst offenders in the industry, and create competition among KE vendors to create the safest possible products. But even when the standard is completed, manufacturers will need to opt in for it to matter, and police agencies will need to decide it’s worth buying munitions under this standard, too.

Bir has also consulted on a separate NATO standard that’s been in the works for the last six years. Again, this standard will be opt-in when it’s finalized, and ideally, she hopes that the NATO standard and ASTM standards can align for global consensus.

But truth be told, Bir paints a better picture of the KE performance than I expected, and many of her sentiments are echoed by a second leading expert in the field who spoke on background. In the lab, many modern KE rounds perform to seemingly safe parameters in terms of power and precision, and so, to her, the technological problems behind KE rounds are often the smaller issue. The bigger problems we’ve seen during U.S. protests come from how they’re used in the field by police officers.

In the lab, there is no wind and the targets don’t move. There is also no stress from a tense protest, no mob of people shouting, no adrenaline pumping through the shooter’s veins. Labs don’t make the bad decisions that cops so often do. Though she’s a scientist who studies material physics, Bir is distressed when we speak, admittedly raw from witnessing the protests and the injuries that so many innocent people in the U.S. had sustained from KE rounds over the last week.

“You have these tools. You can test these tools to make sure they fit within a certain specification. But then it’s training, knowledge. There are rules of engagement . . . the whole reason we’re in this situation is that someone didn’t follow rules of engagement,” says Bir, as she begins to cry over the phone. “And I don’t mean to get emotional, but something has to change. We have to be better. I struggle with this because it’s just, I don’t know. It seems daunting at this point. It’s like, we’ve been at this point for how many years?”

Finding an alternative to pain

As a child, Tom Smith was taken by the phasers of Star Trek. For a weapon, they seemed so humane because they immobilized the bad guy without causing any harm. As an adult, Smith tried to make the phaser a reality. He failed at that specific goal, but the result was a wildly successful startup he founded with his brother in 1993: Taser.

Smith built Taser into a $100 million international business over the next 20 years, taking the firearm alternative to 100 countries over his time there. “It is tremendously successful because it has fulfilled a niche. It’s had its controversies . . . and courts have stepped in,” he says, alluding to decades of debates, lawsuits, and regulations around their use in the field. Tasers have been used for police brutality and killed people, too. But many police forces require a simple rule to carry a Taser that doesn’t seem to exist for rubber bullets: If you want to use the weapon, you need to be tased first, to understand the pain you’re inflicting on someone else.

In the 2010s, he left Taser to pursue his passion as a pilot with a plane startup. Then in 2018, Smith was courted back to the less-lethal industry by a company called Wrap Technologies, where he is now president.

[Image: Wrap Technologies]

Inspired by the weapons of Spiderman, Batman, and Argentinian Gauchos, Wrap Technologies released the BolaWrap, which is a sidearm that fires a lightweight bola through the air. A bola is just a string with two weights, so when they strike a person, the string can wrap around their legs or arms with a painless immobilization. It honestly looks silly the first time you see it work, like an impossible cartoon scene happening in real life. But it’s effective at stopping someone in their tracks—without causing pain.

“I can get wrapped 15 times [in a row],” says Smith. “When you look at rubber bullets . . . what are those designed to do? It’s like throwing a fastball at somebody and hoping to stop and hurt them. It’s not going to do anything but that.”

[Image: Wrap Technologies]

The BolaWrap is also designed to prevent the tense escalation of a weapon being aimed at a subject. The sidearm is not shaped like a gun. Instead, it’s a chunky rectangle, held in the hand like a TV remote. It buzzes in your hand when the safety is released. A laser draws a line across the body where the bola will strike. And even if it misses, landing around someone’s neck, the Kevlar cord doesn’t tighten to choke them. (Though there is a risk of injury, especially around the head, due to two fish hooks in the bola that hold the weights on the string.)

Though BolaWrap just went into production last summer, 150 U.S. agencies have purchased them to be used on the streets, including the LAPD, which has trained 1,000 officers on the device. “Ironically, we do have some devices in Minneapolis,” Smith adds.

So why haven’t we seen more devices like the BolaWrap hit the market? Smith argues that the problem of restraining someone in crisis is just very hard. And the Hollywood dreams he’s been inspired to recreate through his career actually have to be invented from the ground up. But the larger issue seems to be that, due to the historically military roots of “nonlethal” munitions, these KE rounds were created to immobilize, even at the cost of pain and injury. They were designed to fit inside existing firearms as an alternative to shooting someone with a real bullet, often as a way for authoritarian regimes to control a free-speaking, free-protesting populace. And that’s exactly what we’ve seen happen yet again today. As protesters have taken to the streets across the U.S. to protest the murder of George Floyd, they’ve been shot, indiscriminately, with military technologies that are known to maim and kill.

“My own personal opinion, and that of several agencies and law enforcement officers I know and have worked with, is that they do not have a role in peaceful demonstrations,” says Bir.

Recognize your brand's excellence by applying to this year's Brands That Matters Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.