Every weekday, my wife and I get about an hour of serenity thanks to a routine we call “learning on screens.”

Our two young children, equipped with a hand-me-down iPad and a Fire HD 8 tablet, open up Khan Academy Kids, and the house becomes a little quieter as they become absorbed in the app’s collection of roughly 1,000 educational activities. During the hours that they ordinarily would have been in school, it’s the one form of screen time that feels guilt-free.

But that surge in usage has also become a source of stress for Khan Academy, a nonprofit organization that offers free online courses and gets most of its funding from donations. Sal Khan, the organization’s founder and executive director, says the kids app alone is racking up deficits of about $3 million per year, and server costs have become a bigger concern than they once were. While Khan Academy Kids isn’t in any immediate danger, the race is on for more funding to secure the app’s future and help it grow further.

“In tech, you have a fairly large investment to build the thing—the content, the software, the infrastructure—but then it scales incredibly,” Khan says. “That’s why I’m out there, hat in hand, trying to get more people to see the benefits.”

The learning algorithm

As a parent, my initial attraction to Khan Academy Kids came from a place of desperation. When schools shut down, I was immediately overwhelmed with educational app suggestions from teachers, parents, and online articles. Many of those apps required pricey subscriptions, and some had deal-breaking flaws. ABCMouse, for instance, would routinely crash on my kids’ sluggish Fire tablet and third-generation iPad, and when the app did work, they’d gravitate toward songs and stories instead of the educational activities in the app’s sprawling menu system. And while there’s plenty of free educational content on YouTube, I’m trying to keep my kids away from noninteractive media during learning time.

Caroline Hu Flexer, who heads the Khan Academy Kids team, says they consult with educators at the Stanford Graduate School of Education to come up with the material. Kindergarten and first-grade activities are based on Common Core standards, while pre-K lessons draw from the Head Start Early Learning Outcomes Framework.

“I think over the years, I feel like I’ve gotten my PhD in education through working with [educators], which is one of the highlights of my job,” Flexer says.

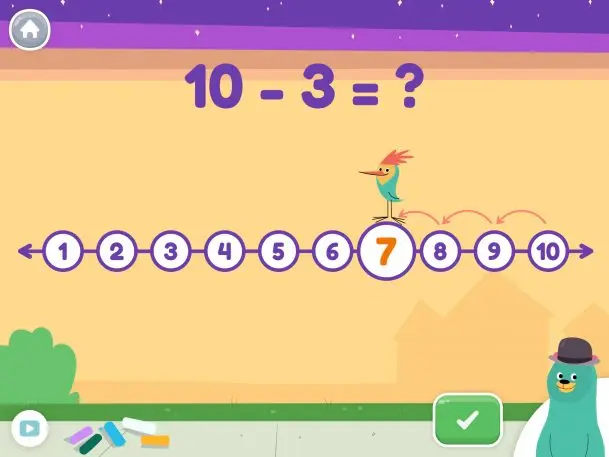

Khan Academy Kids’ cleverest idea, however, is its big green button that loads a steady stream of activities. While it may not be obvious to parents, this button uses an algorithm to figure out which activities to present, and it can ramp difficulty up or down depending on a child’s skill level. The app is even smart enough to shelve an activity if a child is struggling with it, only to bring the concept back later with more lessons and easier practice activities. The idea is to find an optimal challenge level so that kids don’t get bored or frustrated.

“It’s quite nuanced in the background in how we tailor for each individual child,” Flexer says.

Research into the effectiveness of specific educational apps is hard to find, but Khan Academy points to a recent small trial by the University of Massachusetts as evidence that its app is helpful. The study provided a group of pre-K children with tablets containing the Khan Academy Kids app and gave tablets with either a drawing board or a mini piano app to a control group. The kids that used Khan Academy Kids improved their phonological awareness—the understanding of speech structure that helps lead to reading ability—at a level on par with extensive private tutoring.

“The features I would point to that make Khan Kids effective are that it is engaging, varied, targets the right skills (i.e., the ones that research has linked to later academic success), and scaffolds the material presented so that it’s at the right level for the child,” says David Arnold, the University of Massachusetts researcher who led the study.

For-profit origins

Flexer and her team weren’t always in the business of giving their work away.

In 2008, just after Apple launched the iOS App Store, she founded an app company called Duck Duck Moose with her husband, Michael Flexer, and Nicci Gabriel, a product designer. The Flexers had a 2-year-old daughter who loved singing “Wheels on the Bus,” so they built an interactive version as their first app. It was a homegrown effort, with the husband-and-wife team creating music, Gabriel handling design and illustration, and Michael Flexer writing the code.

The “Wheels on the Bus” app, which cost $3, quickly became a hit, holding the top rank in the App Store’s education category for nine months. Other apps for kids soon followed—including more overtly educational ones—and in 2012, Duck Duck Moose raised $7 million in a Series A round from Lightspeed Venture Partners, Sequoia Capital, and Stanford University.

It didn’t work out that way. In the years that followed, the market for paid mobile apps collapsed as free apps with ads and in-app purchases became the predominant App Store business model. Flexer says she was never comfortable with the idea of upselling young children, but that moral stance left Duck Duck Moose without a sustainable business model. In 2016, the company started looking around for an acquirer.

Khan Academy turned out to be the ideal match. Sal Khan says his organization had already been considering a version of its free educational courses for young children, and he had long been an admirer of Duck Duck Moose’s work.

Sal KhanI used to always tell the team that if we ever do it, it should be at least as good as Duck Duck Moose.”

“I used to always tell the team—I’m not making this up—that if we ever do it, it should be at least as good as Duck Duck Moose,” Khan says.

Instead of an acquisition, the two groups structured their deal as a donation, with a purchase price of $1 as a legal formality. Duck Duck Moose’s existing apps immediately became free, and Khan Academy solicited a $3 million donation from Omidyar Network to begin developing what would eventually become Khan Academy Kids. To Khan’s surprise, Duck Duck Moose’s investors were okay with the idea of donating the company instead of turning a profit.

“There was understanding of what our mission and what our team was about, and how big of an impact we can make with Khan Academy,” Flexer says of her company’s investors. “There was very unusual support for that over taking the acquisition route.”

In search of sponsors

When my kids started using the Khan Academy Kids app, I assumed it was in solid financial shape. That changed in May, when I received an email asking for a donation. The app had seen “a spike due to school closures and an increase to our server costs,” the email said, reminding me that it relies on “support from parents like you to keep going.” (I donated.)

Still, small donations only made up about 12% of Khan Academy’s revenue in 2018, according to the organization’s most recent annual report, while 57% comes from a much smaller number of individuals and foundations.

To address costs on the Kids side, Khan says he’s pitched large corporations on the idea of sponsorships, including “three serious conversations” with companies he won’t name. None of those conversations came during the pandemic, but he’s hoping to rekindle some as the Kids app has gained relevance.

Khan says the organization’s financial situation isn’t dire, but as a whole it’s running up a deficit of about $10 million this year. Now, it’s banking on the idea that it can attract some new donors. For Khan Academy Kids in particular, more funding would help it expand to second or third graders—support for first-grade lessons arrived in early March—and eventually support other languages, such as Spanish, Brazilian, or Portuguese.

In the meantime, Khan Academy Kids is operating on the assumption that more funding will come through.

“What I’ve told the team is, this is our moment to step up,” Khan says. “Let’s step up and do what we think is right, and hopefully the universe will conspire to recognize that. I have my fingers crossed.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.