More than 30 million Americans have filed for unemployment in the last six weeks, and millions more have tried but failed to file claims—and as overwhelmed unemployment offices are slow to pay benefits, many people don’t have the money to pay rent. Millions of people still haven’t received their stimulus checks; in cities like New York, where the rent for a typical one-bedroom apartment is nearly $3,000, a stimulus check for $1,200 won’t go far.

The situation has led to the largest coordinated rent strike in the U.S. in decades: On May 1, tens of thousands of tenants are expected to join together as they tell their landlords they can’t pay rent. Some tenants who still have jobs will participate in solidarity. But for most, “this isn’t a matter of choice,” says Peter Meyer Reimer, an organizer with the groups Five Demands Global and Rent Strike 2020. “Thirty percent of Americans didn’t pay any rent at all last month, and this month it’s only going to be worse. A lot of those people are involuntary rent strikers. We’re trying just as quickly as we can to connect them up with other people so that they have some political cover, and so they have a chance at getting out of this without being saddled with debt for something that’s not their fault.”

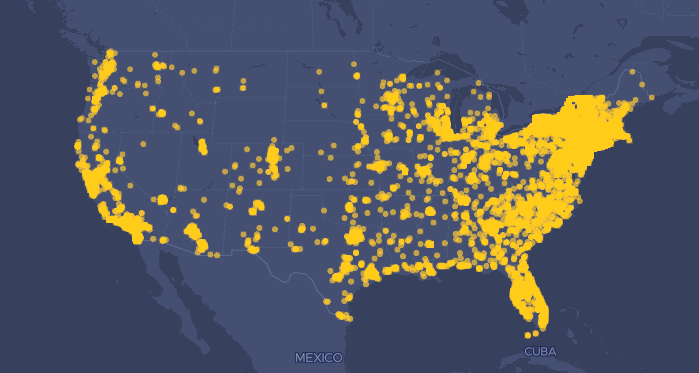

In L.A., membership in the Los Angeles Tenants Union grew from 3,000 tenants before the pandemic to 8,000 by the middle of April; those tenants are all expected to strike. In New York, nearly 12,000 people have pledged not to pay rent on May 1, and some have coordinated building-wide strikes. Nationally, nearly 200,000 renters may participate.

While many tenants have temporary protection from eviction through local or state laws or the CARES Act, they also realize that if they’re not earning money now, they’ll struggle to pay back rent even when they’re working again. By coordinating rent strikes, tenants hope to have more leverage against landlords as they completely forgo rent during the crisis. “They can’t evict us all,” says Meyer Reimer. “And if it’s just a small segment of people—if it were only involuntary rent strikes and everyone else, were draining all their coffers to pay, or if it were only a person here, a person there—they get hosed by the legal system. But our courts are in no condition to process 300 million evictions if it’s everyone in the U.S. who’s doing this.”

Many groups are using strikes to push for changes in policy. In New York City, a coalition of tenants and activists called Housing Justice for All wants rent to be canceled either for four months or the duration of the pandemic. They also want to freeze rents so they don’t go up during the crisis, and they’re calling for housing for those experiencing homelessness and new investment in public and social housing.

A housing justice platform called Our Homes, Our Health offers a model policy that cities or states can adopt to cancel rent and mortgage payments, and reclaim properties on the verge of foreclosure to ensure that they can be used for affordable housing. “Coming out of the 2008 mortgage foreclosure crisis, we saw so much housing get snatched up by private equity investors, who have been some of the worst offenders of forcing evictions, raising rents, causing displacement,” says Chris Schildt, a senior associate at PolicyLink, the organization that helped create the new platform. “So let’s think of how we come out of this crisis reversing that trend, where we’re able to create buyout funds to bring that housing stock out of the private, profit-driven market and back into affordable housing.”

“We know how much the housing system completely fails low-income communities, especially communities of color,” she says. “We want to see solutions that don’t just go back to that status quo, which was a perennial crisis in our communities, but instead moves us a step forward to a more equitable housing system.”

There are some small signs of political support for rent and mortgage cancellation. A state bill was introduced in New York, and some city councils have issued proclamations calling on other states to cancel rent payments. Congresswoman Ilhan Omar introduced a federal bill that would cancel rent payments from April 1 through the end of the crisis. A handful of landlords have also voluntarily canceled rent. In the meantime, rent strikes will continue. Meyer Reimer argues they should go even further. “This is not a time when people can be paying student debt,” he says. “It’s not a time when people can be paying mortgages. It’s not a time when people can be paying rent. It’s not a time when people can be paying utilities. This is a time where so many people are just out cold.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.