Reginald Andre did exactly what he was supposed to do.

The day that the federal government launched the Paycheck Protection Program to give forgivable loans to small businesses struggling amid the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic, he sent in his application. Andre, the 38-year-old owner of Ark Solvers, an IT services company in Miami Gardens, a largely African-American neighborhood north of Miami Beach, had seen his revenue drop 25% and was trying to avoid laying off any of his nine employees. “I was desperate,” he says, recounting the long days and nights of anxiety over the fate of his business, which he started in 2010 and was named last year as one of Florida’s fastest-growing tech companies.

From the start, there was no communication about his application: “I went through the process and it was very smooth and very easy and then that was it. Silence.”

Almost a month later, Andre is still waiting.

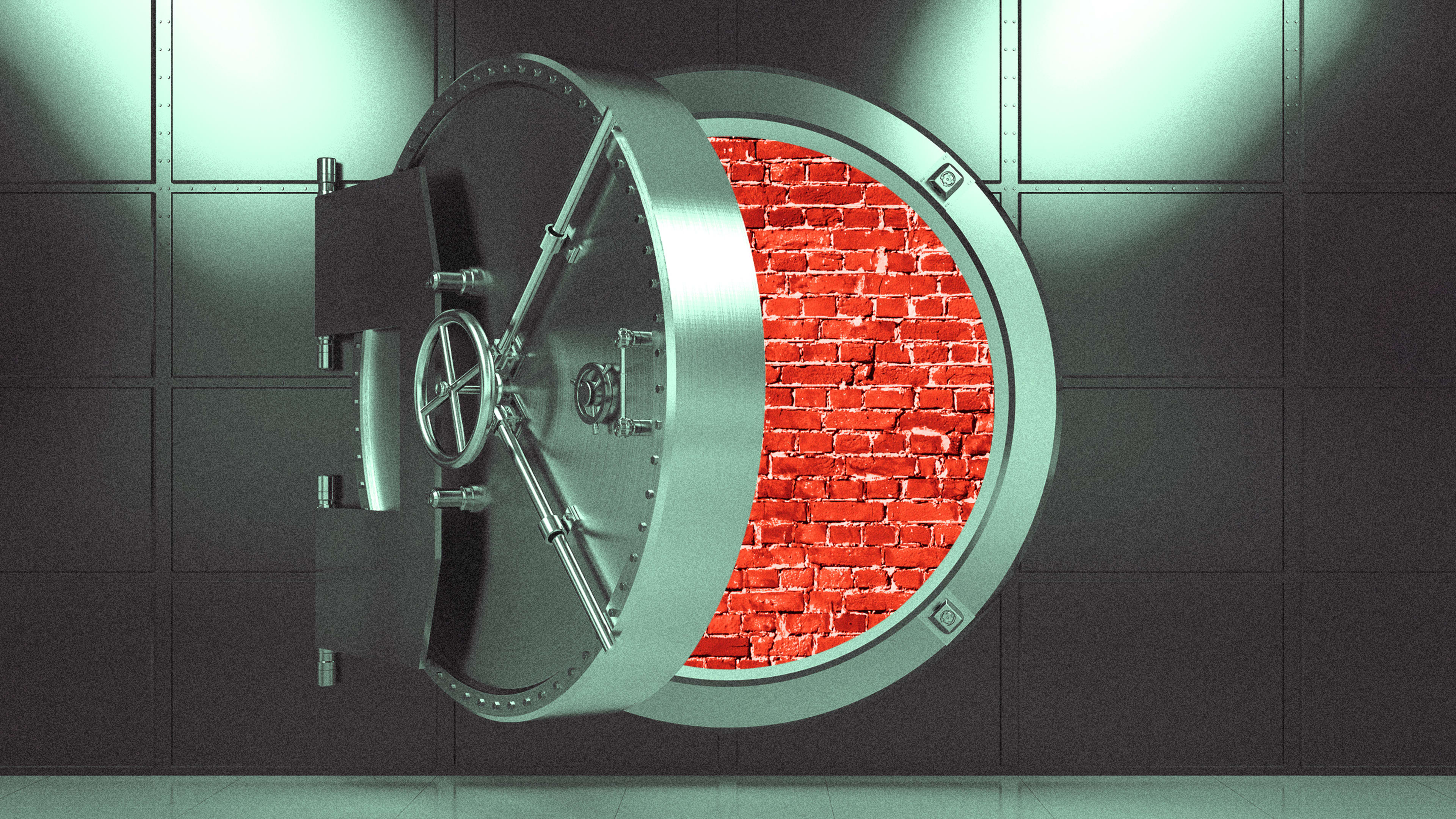

Along with hundreds of thousands of small business owners who have fewer than 20 employees (which constitute the vast majority of employers in the country), Andre did not benefit from a program that was expressly intended to help entrepreneurs like him. The $349 billion program ran out in two weeks, amid widespread accounts of large public companies and businesses that hired well-connected lobbyists, getting millions in loans.

A spokesperson for the SBA did not reply to a request for comment.

That assessment was echoed by Teri Williams, the president and COO of OneUnited Bank, the largest black-owned bank in the country, who says that she can “count on one hand” the number of her customers who received PPP loans. “We saw that our community—minority-owned businesses—were being locked out of the first round [of the program],” she adds.

Williams notes that the application for PPP didn’t ask for the demographic info on the business owners (such as whether they’re members of a minority group or women), which is typical for SBA loans. In meetings with the SBA, she has requested that such information be requested on the PPP application form in the future, but has not received a reply from the agency.

Due to the minority underbanking crisis, especially since African-American and Hispanic communities have been hardest hit by the coronavirus, Williams says that her bank decided over the weekend to participate as a lender in the second round of the program, which launched this week with an additional $310 billion in forgivable loans to small businesses. About $60 billion of that has been set aside to be disbursed by small banks and community lenders.

OneUnited is taking part in PPP despite the fact that the bank does not typically do business loans and tends to focus on real-estate-secured loans. The bank is a designated Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI) since it lends to minority and low-income communities.

“A lot of our customers applied with the larger banks and were not successful, so we said we’d like to do this—and we need to do this,” says Williams. “It’s a challenge for us, since we’re not used to these types of loans. It’s like building a rocket ship in flight.”

Already, the new round has been swamped with applications, amid concerns that it still doesn’t go far enough. Part of the $60 billion set aside for small banks is intended for financial institutions with fewer than $10 billion in assets. But that provision “is not nearly as effective as it could be for getting funds to minority-owned banks and CDFIs because literally 98% of banks and credit unions are below $10 billion in assets,” says Harrington. In essence, the vast majority of the new funds will be handled by large banks, many of whom were criticized for taking huge fees in the first round of the program.

The disparity is particularly troubling since minority-owned banks and CDFIs “have the best track record in history of serving businesses of color,” emphasizes Harrington.

Andre keeps working but he is increasingly worried. “I still go to the office though my team is fully remote unless it’s an emergency, but all the big projects have halted.” He belongs to a chat group for hundreds of IT people, and only one of them was approved for a loan. Andre says he’s “burning” through his reserve capital, stopped all overtime, and is reaching out to his landlord about getting some leeway on the rent, but has yet to get a response. Though he’s trying to avoid layoffs, he is considering an across-the-board pay cut if necessary.

“This is one of the poorer neighborhoods in the region, and this state has thousands of deaths, but we’re not getting the help we need.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.