The open office has taken over modern business. While controversial, these large, open spaces—punctuated by conference rooms and phone booths—are the design of the day, and their proponents claim they increase collaboration. But open offices are also a communal petri dish. In the age of COVID-19, they’re the antithesis of social distancing.

Open offices will need to change for us to go back to work, but how drastically? We talked to Todd Heiser, a co-managing director at the world’s largest architecture firm Gensler, and Primo Orpilla, cofounder at the interior design company Studio O+A, which has designed open office headquarters for companies such as McDonald’s. Both have already been working with companies to adjust floor plans and practices in anticipation of bringing employees back to work. Here are the trends they see coming.

Open offices will get a lot more open again

One truth about the open office is that it has gotten a bit less open over time, simply because we’ve started packing a whole lot more people in. That’s a problem when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is suggesting at least 6 feet of space between people.

According to Orpilla, the prototypical open office should be designed to allow people to meander through the space and find their own nook or cranny to settle down in, without bumping elbows with a coworker.

“Anytime you look at a well-designed open plan, there’s only about 30% of people sitting at the desk. The rest are using other parts of the office space, thereby exercising social distancing on demand in their own way,” says Orpilla. “That being said, the target has been painted. Over the last five years, there’s been a push for the open plan model to densify. That’s where you’re seeing the problems. Some places were designed without the additional open areas, meeting spaces, or the right ratio of meeting spaces to headcount. They were not well thought-out.”

Already, we’ve seen companies in China mitigate their density by moving employees to staggered-shift work. Meanwhile, Facebook has announced that people will return to the office in waves. Other companies will likely take the same approach.

“In the beginning, maybe 20% of people will go back to work,” says Heiser. “Perhaps late summer next year we could see those densities grow.” Gensler has also been developing a tool for clients, which takes existing floor plans, and algorithmically suggests safer seating layouts. That might sound a bit over the top, using AI just to spread people a minimum distance apart, but several of their clients are working with over a million feet of office space. Some automation will be necessary.

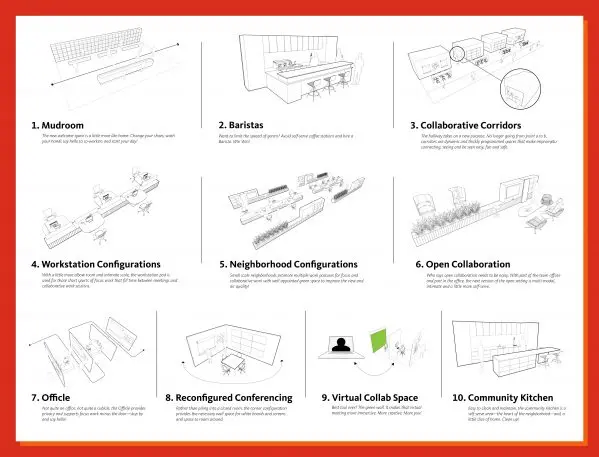

The new welcome space—a mud room with thermometers

If you’ve visited an open office in the past few years, you’ve probably been greeted by someone sitting at a desk. They point you to the coffee—either K-cups or brewed thermoses—and you help yourself before poking around a basket of fruit, then take a seat.

This is to make visitors feel comfortable without a lot of staff oversight. But comfort going forward will be about perceived safety, which is why self-serve coffee may not come back as designers reimagine office entries to deal with visitors and staff who need to decontaminate before entering a shared space.

“We’ve been thinking, what’s the new paradigm? Maybe it’s a mud room,” says Heiser. “You come in, change your shoes, wash your hands. Will sinks become primary in entries instead of self-service coffee?”

Many offices have such spaces, full of lockers, bike storage, and even showers. But these have been facing side doors and rear entrances. Now, these spaces might face everyone who visits an office. They might even be a place to run health screenings for anyone who comes into the building. “If we let someone in the building, [they might] infect people,” says Orpilla. “So we have to have better checkpoints to screen employees and visitors. We’re going to have to take your temperature [at the door].”

The rise of the clear cubicle . . . an illusion of safety

Here’s a twist: Plexiglass is sold out from many suppliers. Why is that? Because architects and interior designers are securing the transparent material to build clear barriers between people.

“I know there’s a big run on it,” says Orpilla of Plexiglass. “Essentially, we’re creating gigantic sneeze guards. When you think of it, it’s like a sneeze guard at a salad bar. There are better materials that are more antimicrobial . . . but everyone goes to the clear plastic because the perception is, I have this barrier around me.”

Orpilla says you should expect to see Plexiglass, and other dividers, rise up, creating walls around desks. “One of my clients said the other day, ‘I shouldn’t have gotten rid of all those 65-inch-tall panels,” says Orpilla. “Whether it’s safe or not, people feel safe with a barrier around them.”

New HVAC systems

At the same time, architects are considering airflow and HVAC systems in new ways. In China, buildings have already been designed with more fresh air flow and air filtration than what we have in the United States. Every expert I’ve spoken to, from air flow researchers to architects, agrees that offices across the United States will begin to upgrade their HVAC systems. But not all solutions will be part of the centralized heating and cooling system—at least not at first. Offices will likely install portable air purifiers as a stop gap. Employees may likely bring in their own, too.

Orpilla is experimenting with installing giant exhaust fans, like you see over the smoky grills at Korean restaurants, in Studio O+A’s own office space, for places where small groups of people might meet but still want fresh air. Yet ironically, while cubicles are coming back to seal individual employees inside, shared spaces like small and medium conference rooms may actually be opened up to the rest of the office, to let these rooms breathe.

“We’ve been thinking of it as an ‘officle.’ Not quite an office. Not quite a cubicle,” says Heiser. Such a room would only have three walls, with one open to allow airflow. “It provides privacy and focus work minus a door,” he says.

Communal spaces get repurposed

Mass gatherings are canceled across much of the world, which means no big weddings—and also, maybe no work lunch. Even properly proportioned open offices are often built with cafeterias, which are designed to operate with at high capacity to feed most or all employees meals within a very tight window of time. Expect a lot of desk lunches and outdoor eating instead.

But if everyone doesn’t gather in the cafeteria for lunch, what do you do with that space? That answer is pretty simple: It opens up to more people working through the day, allowing everyone to distance more.

Heiser suggests that another way to avoid big groups inside is simply to move them outside. This strategy doesn’t work so well in dense urban cities, he admits, but in temperate climates like the Bay Area where corporations are set up on large campuses, there’s a lot of potential to just move people outdoors.

The biggest challenge? Getting people upstairs and down halls

For the most part, assuming buildings cut down on headcount and vastly improve their HVAC systems, it seems feasible to enable some social distancing at scale inside an office.

But there are two lingering bottlenecks: elevators and hallways.

High-rises present a particularly tricky situation for socially distanced offices. That’s because thousands of people will come to work in a short time frame, who are actually going to several different offices that may not be coordinating shifts with one another. “You have to get all the people up the elevators or stairwells,” says Orpilla, who notes that some elevators are too small to allow more than one person to ride them in a socially distant way. “We’re seriously looking at ways you can put dividers up in elevators with plastic screens, so you can go to four corners in the elevator.”

Hallways are a similarly tricky proposition. “Most buildings didn’t build very wide aisles, so you can’t maintain 6 feet,” says Orpilla.

As a result, many designers are looking to instruct employees to actually circulate in one direction through a space, treating hallways as one-way streets rather than two-way streets.

It’ll change, and change again

Ultimately, many of the above ideas will be tested in the field, and soon. Companies have already started planning COVID-19-responsive conversions to office spaces, as states like California detail their plans to reopen. Some of these ideas will work while others won’t. But it’s important to note that these plans are all based upon the relatively vague advice of hygiene and social distancing provided by WHO and the CDC. Both Heiser and Orpilla expect that standards will quickly change as scientists and health officials learn more about COVID-19 and update best practices. “That change may happen on a month-to-month basis,” Heiser says. And companies will need to continually adapt their workplace to keep up.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.