As the United States looks to slowly return to something resembling life before the coronavirus pandemic, officials and researchers have been considering ways to continue reducing the spread of COVID-19.

One potential tool is what’s known as contact tracing—determining who was in contact with someone who has the virus, and then notifying them that they’ve been exposed. That lets people who might be infected take precautions such as quarantining themselves until they test negative or recover, which can reduce the risk of spreading the virus. Already, health agencies in states including California, Massachusetts, Illinois, and New York have announced plans to deploy potentially unprecedented numbers of human contact tracers. These employees would interview people who have the virus and warn their contacts to isolate themselves and consider medical attention as appropriate.

At the same time, tech companies and researchers have announced plans for automated contact tracing. In a rare joint move, smartphone operating system rivals Google and Apple released more details this week on “privacy-preserving contact tracing” slated to be added to their phone software. It would allow for public health organizations to build apps that could use cellphone Bluetooth signals to track who users were exposed to. Then, if someone tests positive for the coronavirus, the apps could notify those who had been near them—without compromising anyone’s privacy, the companies say. Other researchers and companies have also begun developing apps and standalone devices with similar intent, and some countries internationally have already deployed such apps.

“We want to be able to let people carefully get back to normal life while also having this ability to carefully quarantine and identify certain vectors of an outbreak,” said Ron Rivest, an Institute Professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in a statement. Renowned for his work on computer security and cryptography, Rivest is the principal investigator on one such project to trace contacts via Bluetooth signals.

Stefano TessaroThe entire approach relies on as many people as possible using it.”

But, experts say, whether these apps will make a difference still remains in question. It’s unlikely that contact tracing apps or hardware will be legally required, and multiple surveys have suggested the American public is skeptical that they’d be effective. That might be a self-fulfilling prophecy, since if people are unwilling to install the apps, they won’t be useful at actually stopping the virus: One Oxford University study estimated that in a city of 1 million people, it would take 60% of the population installing such an app to shut down the epidemic, although lower levels of use could still make a difference.

“The entire approach relies on as many people as possible using it,” says Stefano Tessaro, an associate professor at the University of Washington’s Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering.

There’s also the fact that millions of people don’t own smartphones, including many older people considered more at risk from the disease. And even developers of contact tracing apps—including Tessaro, who’s involved with an app called CovidSafe that uses Bluetooth for contact tracing and also lets users with the virus track their symptoms—emphasize that they should be used in conjunction with human-driven contact tracing. Ultimately, the technology is still unproven.

Widespread public reluctance

One significant question is simply whether people will install contact tracing apps once they are available. A recent Pew Research Center survey found that 60% of Americans don’t think tracking people’s cellphone locations to monitor potential virus spread would make much of a difference, and only 52% say it’s “at least somewhat acceptable” to use the data for that purpose. That’s potentially worrisome for pandemic control strategies relying on the apps, since they only become effective with widespread use.

The Bluetooth-based technology some researchers are now proposing doesn’t use GPS-style location data. Instead, the technology detects which phones were near one another, without logging where people were at the time. That could potentially preserve privacy while being more accurate than GPS, which can be too imprecise to say definitively who was less than six feet away.

“Think about in cases where you’re using Google Maps or something on your phone, and it thinks you’re on the wrong street corner,” says Neema Singh Guliani, senior legislative counsel at the American Civil Liberties Union.

Neema Singh GulianiThink about in cases where you’re using Google Maps . . . and it thinks you’re on the wrong street corner.”

But even Bluetooth proximity checks may still make people uncomfortable. A Washington Post-University of Maryland poll released April 29 found that, on being told about Apple and Google’s plan to enable proximity-tracking apps, respondents were split 50-50 on whether they’d use such an app.

Some virus-tracking apps do in fact use location data: The New York Times reported this week that North and South Dakota authorities are promoting the use of an app called Care19, which stores location information. The app makers say they’ll later augment this location data with Bluetooth proximity records. Only about 3% of North Dakota residents have downloaded the app, the Times reports.

Leaving out people without smartphones

Of course, not everyone has a phone that can install apps at all. The Post-Maryland poll reported that about one in six Americans don’t have smartphones, and that number goes up to 47% for people 65 and older, a population considered more susceptible to the disease.

Alvaro Bedoya[States] are missing half of one of the most vulnerable populations.”

“As states pour their resources into contact tracing tools, they are missing half of one of the most vulnerable populations,” said Alvaro Bedoya, founding director of the Center on Privacy and Technology at Georgetown Law, in a statement. “There is a real disparity here.”

Any kind of contact tracing that relies heavily on smartphones may just exacerbate inequalities between the people and communities that have them and those that don’t, says the ACLU’s Guliani. “We also have not seen the same level of attention to erasing the fact that black people are dying from this disease at far higher rates than white people,” Bedoya said.

There’s also a danger that any businesses or institutions that require visitors to have contact tracing apps installed might end up discriminating against people who don’t have sophisticated phones. The ACLU has generally said tracking apps should be only voluntarily deployed, not used to implement any kind of punitive measures, and designed with privacy in mind.

An overabundance of apps

Another potential concern is the sheer number of contact tracing apps. Confused users who do download one app may not receive warnings when someone who has downloaded a competing app exposes them to the virus.

“We don’t want to have too many apps floating around,” says David Quimby, principal at St. Paul, Minnesota, business innovation consultancy Innovation Radiation. “We want to have a finite number.”

Apple and Google have said they want to work with “public health authorities,” which would create the actual apps that interoperate with their systems. (Neither company responded to multiple inquiries from Fast Company for this article.) That could mean one clear set of Android and iOS apps recommended by authorities in particular places, perhaps with adjacent states agreeing to use the same app. But that could still mean people who regularly commute or otherwise travel between jurisdictions might need multiple pieces of software on their phones to fully participate.

David QuimbyWe don’t want to have too many apps floating around.”

There are also multiple apps being produced by academic teams, although university researchers have generally been open to efforts to collaborate, says Tessaro, who mentioned regular communication with the team at MIT.

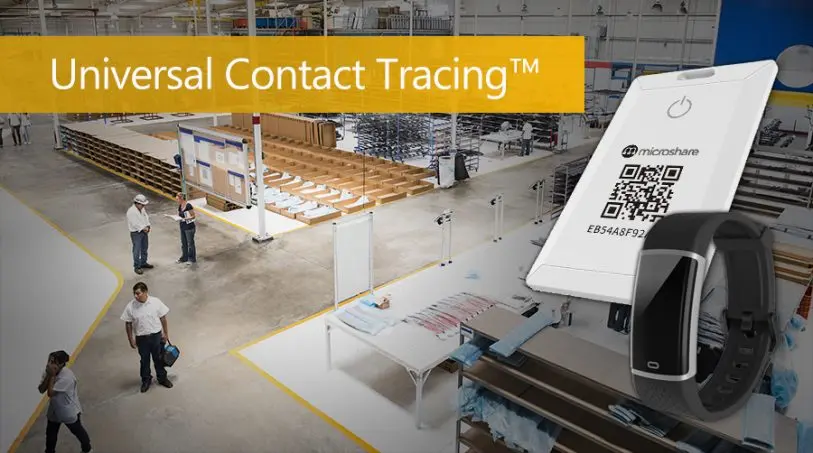

Besides, there are locations, including workplaces, where cellphones aren’t permitted or are frequently left in lockers or cars, making them ineffective at tracking exposure. Microshare, a Philadelphia company that uses sensors to track the location of items such as hospital beds and wheelchairs, has developed Fitbit-style wearable Bluetooth devices. They can be used for workplace proximity tracing even where cellphones aren’t allowed.

“We realized that tracking employees inside a building wasn’t dissimilar to tracking hospital beds,” says Microshare cofounder and CEO Ron Rock.

Rock says that there’s no reason people couldn’t have both a standalone device for contact tracing in the workplace and a smartphone app they use elsewhere. But it’s unclear whether users will in fact install smartphone contact apps for personal use if they already have a standalone device they’re using for work.

Will the apps be accurate?

Despite the promise of smartphone contact tracing apps, it’s still unknown whether they’ll be accurate enough to do more harm than good. A team of researchers writing in the Brookings Institution’s TechStream publication suggested the apps could generate false positives and negatives. Those would come from instances where people did not encounter someone with the virus but received a notification anyway, and instances where people were actually exposed but were not notified. By definition, a contact tracing app would also fail to detect where COVID-19 was transmitted by other means, such as contaminated surfaces.

“Fleeting interactions, such as crossing paths in the grocery store, will be substantially more common and substantially less likely to cause transmission,” they wrote. Leaving those encounters out could mean not warning people about their possible exposure to the virus. But sending too many warnings could lead to panic or frustration if people are asked to repeatedly quarantine themselves.

Ryan CaloIt could be constantly telling you that you’re at risk when actually the risk was very low.”

“It could be constantly telling you that you’re at risk when actually the risk was very low,” says Ryan Calo, an associate professor at the University of Washington School of Law and one of the paper’s authors.

The exact technology used will also likely make a difference. Bluetooth is widely considered more accurate for contact tracing than GPS. Po-Shen Loh, an associate professor of mathematics at Carnegie Mellon University, has launched an app called NOVID, currently in beta release, that further augments Bluetooth with ultrasound signals to boost accuracy. The app plays and detects sounds too high-pitched for the human ear to hear, then uses the speed of sound to measure distances between devices. About 1,000 people have downloaded the app so far.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o4gZxI0Zkqs&feature=youtu.be

“If it’s in a bag or a pocket, what happens is that the sound is more muffled,” Loh says. “However, the time it takes the sound to get to you is still the same.”

Even if apps can accurately detect when people were physically present together—and not, say, in adjacent offices or cars with signals passing through walls—there’s still a risk that they’ll miss cases of potential transmission.

That’s not to say that there’s no role for smartphone apps and other technology in fighting the coronavirus, Calo says. He suggests manual contact tracers could use apps to track overall infection data, peruse patients’ location history as part of an interview process, and send out notifications. The New York City Health Department, for instance, plans to use apps to communicate with patients and their contacts if they wish, with the details yet to be determined, a spokesperson said in an email.

Generally, Calo says, it would be surprising if digital technology plays no role in fighting the further spread of the virus. But that doesn’t mean tech is a silver bullet. “It would be equally surprising if an app could get us out of a global pandemic,” he says.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.