As Amsterdam plans for its post-coronavirus recovery, it’s also rethinking what economic success looks like. In doing so, it’s not looking at traditional financial metrics of how to determine when the city has recovered. Instead, the city will be the first in the world to officially adopt the “doughnut” model of economics.

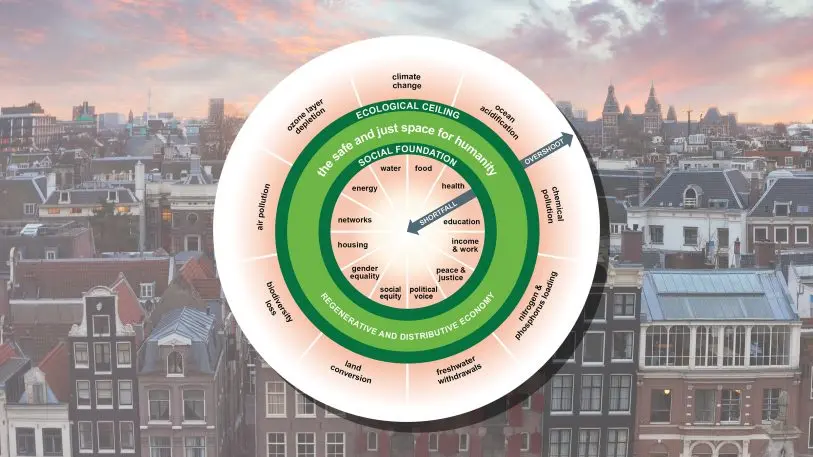

The model, developed by U.K. economist Kate Raworth, is a simple way to illustrate a complex goal. The inner ring of the doughnut represents minimum standards of living, based on the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. This entails the basic essentials everyone needs to thrive, from food and clean water to gender equality and adequate housing. According to the model, no one should fall into the hole in the center of the doughnut, which would mean they don’t have enough to afford basic needs. The outer ring of the doughnut represents the ecological limits of the planet, from biodiversity loss and air pollution to climate breakdown. Amsterdam wants to stay between the inner and outer rings.

“Within these two boundaries, between the social foundation that is on the inside and the ecological ceiling, there is this doughnut-shaped space where it is possible to meet the needs of all within the means of the living planet,” says Ilektra Kouloumpi, a senior strategist at Circle Economy, a nonprofit that has been working with Raworth, along with the nonprofits Biomimicry 3.8 and C40 Cities, to help the Amsterdam government adopt the doughnut model to make policy decisions. “The overarching question is: How can our city be home to thriving people, in a thriving place, while respecting the well-being of all people and the health of the whole planet?”

The city already has ambitious environmental goals, including a plan to become carbon neutral, and to transition to a circular economy, meaning that all materials will be used in closed loops instead of ending up in landfills. But it also recognized that it needed an overarching strategy that included social goals. Circle Economy, which was already working with the city on its circular economy goals, saw the opportunity for the doughnut model to help the city create better strategies. The planning has been underway for more than a year; the city formally adopted the model last week.

“The big added value of putting this in the heart of the city’s vision is that it creates a holistic vision where all the different agendas that the city drives and all the different targets that the city needs to fulfill sit together within one common vision,” Kouloumpi says. “I like it because it’s for the first time that we can see important topics like climate change and gender equality, or health education and land conversion—very different angles—coming together under one conversation.”

In a series of workshops, the city and groups of stakeholders looked at Amsterdam’s current status through the lens of the doughnut. Housing, for example, is one local social challenge, as nearly 20% of tenants can’t afford to pay for other basic bills after paying for rent. It’s simultaneously a climate challenge. Now, Kouloumpi says, as the city thinks about how to add housing, it’s also thinking about how housing impacts issues such as air pollution and health. “We’re really thinking about the interconnections,” she says.

The approach also looks at the impacts the city has beyond its own borders, from the air pollution that’s created in China when Chinese factories make goods that are exported to the Netherlands, or the social impact of the cocoa grown in Africa—sometimes with child labor or slavery—that’s imported in huge quantities through the Port of Amsterdam. “It stretches the boundaries of responsibility of the city,” Kouloumpi says.

The analysis helped the city create a “city doughnut,” a visualization of the city’s challenges that is helping it decide what changes are needed and whether the plans it has in place are ambitious enough. The doughnut model is also helping it evaluate new policies that can solve its challenges. The coalition of groups working on the project, called the Thriving Cities Initiative, is also beginning to work with other cities; both Portland, Oregon, and Philadelphia have also created city portraits, though they haven’t yet been published. “The idea is that we pilot this program and we work now with these three cities, and once we have created that complete journey, then more cities can take this path,” says Kouloumpi.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.