The COVID-19 crisis has upended urban life as we know it. Cities are on lockdown, and the once bustling streets of Paris, New York, London, Rome, and more now sit virtually empty. Technology has been critical to the way cities and society have coped with the crisis. Online delivery companies have been essential for getting food and supplies to residents, while their restaurant delivery counterparts have helped keep restaurants up and running during the lockdown. Urban informatics has helped track the virus and identify infection hot spots. In the not-too-distant future, as cities begin to reopen, digital technology will be needed to better test and trace the virus as well as to ready urban infrastructure, like airports, public transportation, office buildings, and businesses, to open back up safely.

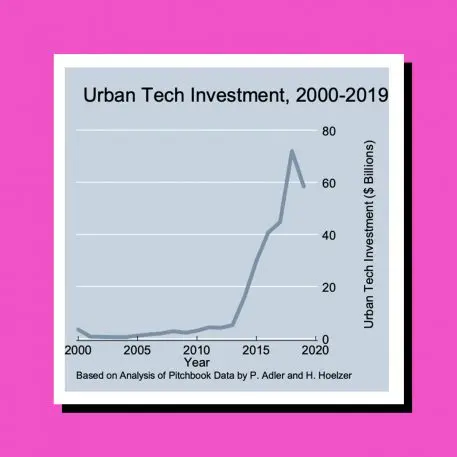

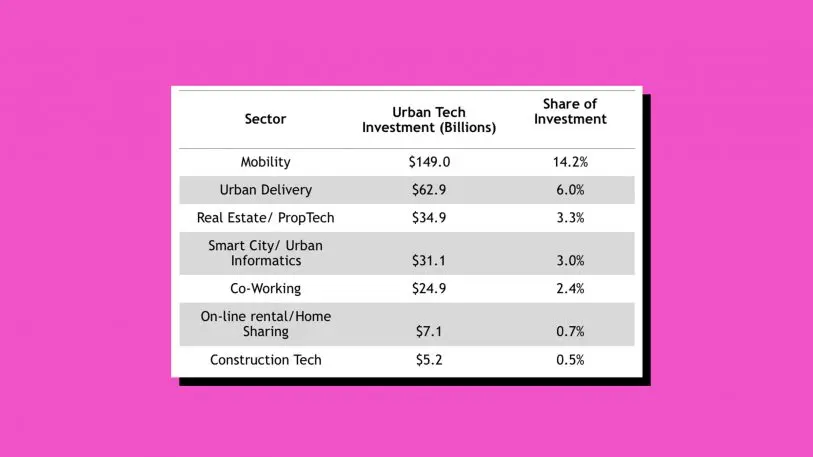

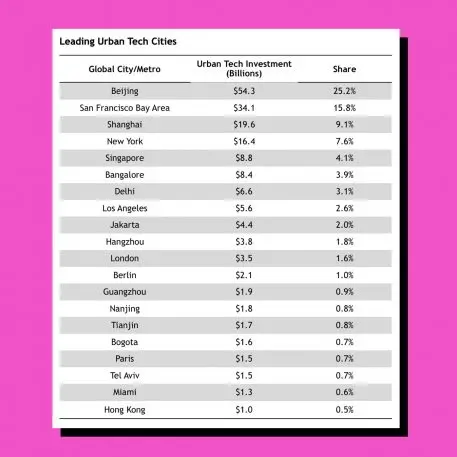

Urban tech has grown at an astonishing clip over the past five years. Global venture capital investment in urban tech surged from virtually nothing in 2010 to some $20 billion in 2015 and $70 billion in 2018, based on our analysis of data from Pitchbook. (Our data covers 128 nations and 669 global cities or metro areas). Investment ticked slightly downward in 2019 as some well-known urban tech companies like WeWork and Uber struggled to meet investor expectations. Still, global investment in urban tech averaged some $65 billon a year in 2018 and 2019, comprising more than a fifth (21.4%) of all such investment.

Some urban tech industries like coworking and online rental will be hard hit by the COVID-19 crisis. Others, like urban delivery and urban informatics are likely to grow in importance as we recover. The larger takeaway is that urban technology will play a crucial role in determining which cities thrive, and which ones falter, in the wake of COVID-19.

The winners, losers, and heroes of urban tech

The lockdown has been a massive opportunity for urban delivery firms that provide groceries and needed supplies as people shelter in place. Instacart announced in late March that it would be hiring 300,000 more employees, while Amazon is looking to add another 100,000 employees to its warehouse and delivery operations to keep up with demand. DoorDash’s advertising slogan, “Never Leave Home Again,” has taken on new meaning in a time of social distancing.

In Italy, where online shopping makes up only 4% of total retail sales, the supermarket chain Carrefour reported a tenfold increase in orders during the lockdown through its partnership with logistics startup Glovo. French customers bought food through the startup Ollca, which delivers goods from the local online boulangerie, butcher, or fishmonger. Demand for delivery is likely to continue even as lockdowns are lifted, especially if people remain afraid of contacting the virus, and lines are still longer at stores as social distancing continues.

Another big winner is urban informatics. Technology has been, and will continue to be, key to monitoring hot spots and tracking people with the virus. Temperature readings from Kinsa’s digital thermometers were used to identify hot spots in the United States early on. Cellphones in South Korea vibrate with emergency alerts whenever new cases are discovered. Smartphone apps provide detailed timelines of infected people’s travel and movements. Singapore’s TraceTogether app uses Bluetooth signals between phones to gauge the distance between users, and the duration of such encounters. VigilantGantry, an AI-driven temperature screening technology, integrates disease monitoring into heating and cooling systems. In April, Apple and Google announced a partnership to enable iPhone and Android phones to alert people who may have come in contact with COVID-19. As the economy reopens, airports, convention centers, arenas, office buildings, and schools will likely be retrofitted with health and temperature screening.

Mobility enterprises like Lyft, Uber, and Lime may also fare surprisingly well. Prior to the crisis, they made up the biggest single sector for urban tech investment. In the short-term, ride-share services have suffered since few people are traveling during the lockdown. However, as the economy reopens, but people remain fearful of buses, trains, and other forms of public transit, demand for ride-share services will likely grow, with demand for scooter and bike shares growing even more.

The pandemic has hit hard at coworking firms, like WeWork, which were already struggling before the crisis. A survey of more than 14,000 coworking spaces in 172 countries in March found that nearly three-quarters (72%) saw a significant drop in the number of people working from their spaces. The long-term risk is that customers might never return. In early April, Softbank terminated its deal to purchase an additional $3 billion worth of equity in the company, citing the company’s governance, not the fallout from COVID-19 crisis, as the cause. But it stands to reason that coworking spaces will not weather the storm. Before the pandemic, being surrounded by new and different people seemed energizing and exciting. That will not be the case in the future when fear of viral exposure is top of mind.

Short-term rental companies saw reservations evaporate as travel was restricted and cities locked down. In many cities, hosts have had little choice but to convert their buildings and apartments into longer-term rentals. The hotel industry will be slow to rebound with rooms heavily discounted, putting additional pressure on the short-term rental sector.

Across all of these urban tech sectors, the true heroes of the crisis have been the frontline workers who have done so much to keep our cities up and running. These workers are organizing to demand higher wages or so-called hazard pay and better protective equipment from urban tech companies like Instacart, online retailers like Amazon, and grocery chains. The crisis shines a light on the trying conditions facing urban tech’s gig workers and is likely to spur an ongoing movement to improve both their pay and working conditions.

An opportunity to rethink infrastructure

Urban tech will also play a key role in retrofitting cities. Previous pandemics have shaped the adoption and adaptation of urban infrastructure. The 1918 Spanish flu pandemic led to upgrades in urban sewer and sanitation systems and new building codes that called for improved lighting and ventilation. We’ll see similar transformations as a result of COVID-19.

For instance, people will be afraid of crowded trains, buses, and subways as the economy begins to reopen. As they revert to their cars, the flood of traffic threatens to worsen already substantial congestion in large cities and metro areas. Sensors can be used to track road congestion and help mitigate it.

Streets will also need to be retrofitted to support increased demand for walking and biking. Cities like Oakland, California, are already pedestrianizing streets to promote social distancing. As cities reopen and recover, streets can be redesigned and supported by technology to more adequately encourage different kinds of mobility, like walking, biking, delivery vehicles, and ride-share vehicles.

The dominance of urban tech clusters

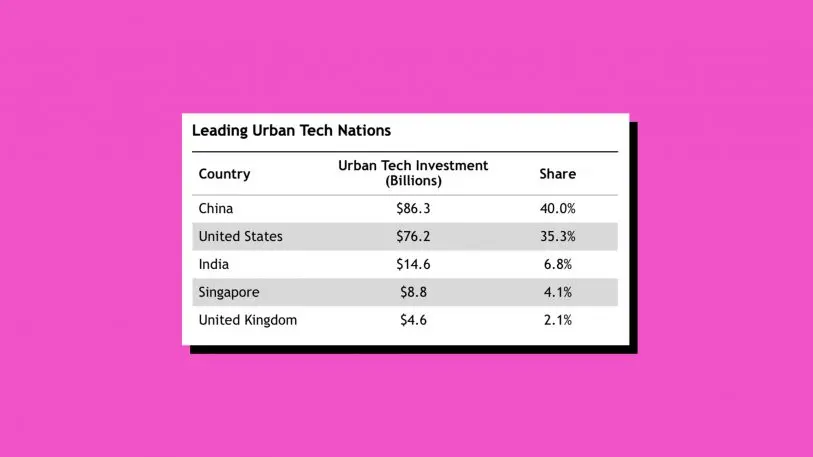

The cities and nations that are home to leading urban tech clusters will be able to reopen and recover more quickly, providing an economic edge. Up until recently, the United States was the unquestioned leader, accounting for more than 95% of all global venture capital investment until around the year 2000. By 2017, that share had fallen to just 50%. The United States ranks second to China in urban technology, controlling just 35% of global investment compared to China’s 40%. But the United States remains on top with roughly three times the number of urban tech deals as China. (China’s investment totals reflect a small number of mega-deals). Europe lags with less than 5% of global investment.

The role of urban tech companies in mitigating the COVID-19 crisis may help mute some of the so-called “techlash,” driven by concerns over privacy, political abuses of social media, and the affordability and inequality of leading superstar cities. As Ezra Klein put it: “I care about my privacy, but not nearly so much as I care about my mother.” Still, it remains essential to put in place new and more robust governance mechanisms and institutions that can protect privacy and anonymity, while ensuring people and communities are safe.

The places that develop and deploy these urban technologies effectively will have a leg up in public health, until the virus is controlled or vanquished. No doubt, their economies will also rebound more quickly. Cities may never return to the way they were before coronavirus. But that might not be such a bad thing.

Richard Florida is university professor at University of Toronto’s School of Cities and Rotman School of Management, distinguished fellow at NYU’s Schack Institute of Real Estate , and cofounder and editor-at-large of CityLab. He is the author of The Rise of the Creative Class and most recently of The New Urban Crisis.

Patrick Adler is research associate at University of Toronto’s School of Cities and Rotman School of Management and a PhD candidate at UCLA.

Henrik Hoelzer is researching cities at Cambridge University’s Department of Land Economy and an advisor to urban tech companies.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.