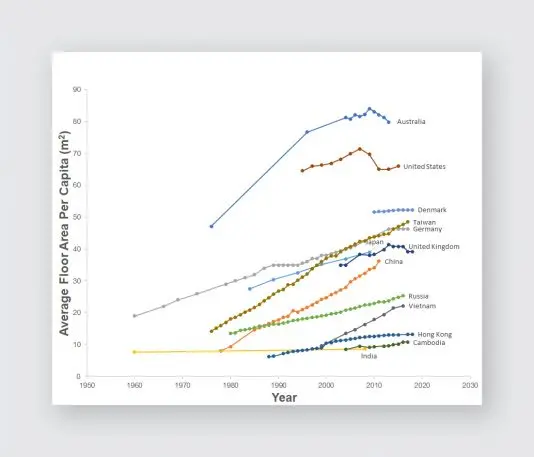

Around the world, more people are living with more space at home than at any other time in history.

This may be surprising–cramped, dingy rooms are as familiar in Shanghai as they are in London. But on average, the space per person in Chinese homes has increased by about 323 square feet in 40 years, and by 43 square feet in the UK over the past 15 years.

This trend is linked to something called the “second demographic transition.” Put simply, as countries develop and individual incomes rise, people prioritize higher order needs, such as privacy, autonomy, and the fulfillment of personal ambitions.

Think of that feeling when you just need time by yourself. In high-income countries, it’s likely that you can expect to find somewhere in your home where you can shut yourself away and do what you want. These expectations can have implications for how much space we might expect per person in the home. Rather than having to watch a show all together in the living room, we might now expect to each have our own computer, or be able to watch our own television in our own bedroom.

Another aspect of this transition is that young people are likely to find partners and become parents later in life. Instead of moving from living with parents to living with a spouse, there are more opportunities to live alone–such as going to university. As a result, the number of people living in a household shrinks.

Likewise, households with multiple generations are on the decline. In Japan, 66% of women surveyed in 1950 expected children to support them in old age. In 1990, this fell to 16%. Some figures suggest that half of over 65-year-olds in high income countries now live alone. This means more one-person households, which drives up the house space per person. Around 40% of Scandinavian households and 30% of U.K. and U.S. households are occupied by one person.

More space, more energy

Having more space per person on average in homes helps reduce overcrowding. That’s good for reducing transmission during the COVID-19 pandemic. It may also mean there is enough space for desks, monitors, and toys for working at home, schooling, and entertaining children.

Nonetheless, there are implications for household carbon footprints. In a nutshell, more space per person is more space to heat per person.

To meet the growth in floor area with higher demand for warm homes, the International Energy Agency suggests energy efficiency would need to improve by 30% by 2025. With this in mind, some energy researchers have argued that without limiting the average dwelling floor area per person, “it is hardly imaginable” that there could be an absolute reduction in household energy demand.

More than information on upgrading boilers or installing efficient light bulbs, marketing about the drawbacks of larger homes and the upside of downsizing could be more effective to reduce energy use. Smaller homes are more affordable, cheaper to heat and cool, demand less time and labor to clean, and maintain and can occupy just one floor–good for people who struggle with stairs.

Since a basic necessity of housing is a sense of personal space and privacy, regulations could improve the experience of living in high-density housing. This could mean giving renters the right to own pets and decorate, or improving the standards of soundproofing. In the UK, poor soundproofing and disturbance from neighbors is one of the most common complaints about living in flats, and why many choose to move into a detached house.

Technology will play a large part in improving energy efficiency and decarbonizing energy. But low-carbon domestic heating systems like heat pumps, biomass boilers, low-carbon design standards, and improved insulation aren’t sufficient on their own. These types of solutions don’t address the root causes of the second demographic transition, which has led to a proliferation of bedrooms and bathrooms and increased expectations of privacy and personal space.

To reduce overall energy demand, we need to start looking much more closely at housing policy rather than improving technology in individual homes.![]()

Katherine Ellsworth-Krebs is a senior research associate at Lancaster University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.