What if someone threw a hacker conference and nobody showed up?

As I boarded a United flight at SFO on March 17, the first day of San Francisco’s shelter-in-place order, that question was on my mind. I wondered just how many people would be attending CanSecWest 2020 in Vancouver, and if I’d be the only one in person.

Car traffic in both S.F. and Vancouver was light, even though Vancouver wouldn’t enact stricter social distancing rules until March 21, the day after I would return home. The airplane was half-empty, and there was no line for security in either airport. It seemed that some people were finally starting to take seriously the spread of the novel coronavirus that’s been plaguing the world.

As bizarre as the lack of bodies on the road and in the plane were, the 20th annual CanSecWest attendance was even emptier. Three attendees showed up in person—not counting me—along with half a dozen staffers. That two-to-one ratio of conference organizer to attendee might seem excessive, except that the personnel were there to run the online component of the conference. This experiment in virtualization might point the way forward for confabs of all kinds, given that Apple, Google, Facebook, Microsoft, and other tech companies all scuttled their plans for the 2020 editions of their in-person conferences months in advance.

CanSecWest is a single-track cybersecurity conference that, in normal times, attracts between 400 and 500 people every March to Vancouver’s Sheraton Wall Centre. That’s about one percent the attendance of the big Def Con event in Las Vegas. But CanSecWest draws a pilgrimage of regulars for its technical, international, and decidedly cozier atmosphere. It’s also the home of the annual Pwn2Own contest, where hackers can win the devices—including Tesla cars—that they compete to break into.

Attending the event in the middle of a pandemic was not a decision that I took lightly, and I acknowledge that I may have made the wrong decision. I had come down with a sore throat a week after attending the RSA Conference and B-Sides SF in February. (RSA was probably the last major tech conference to be held as usual before the cancellations began, and several attendees would contract the coronavirus.) My sore throat went away after a day, and I showed no fever or other symptoms of any kind of illness. Still, con crud or coronavirus? How was I to know? What few COVID-19 tests were available had been reserved for people more at risk than me.

February’s dilemma of how to make the conference safe for attendees stretched into March. Ruiu canceled the midconference nightclub party and then canceled the annual postconference party at the nearby Whistler ski resort. Less than two weeks before, enough attendees had backed out that Ruiu prepared to virtualize the event. All talks would be streamed, and all the presenters except for one would be speaking remotely. The preconference training sessions would continue, but with students remote-accessing the devices they were learning how to hack.

The big decision

Meanwhile, I made it clear to my girlfriend that if she didn’t want me to attend, I would stay home. I discussed the decision at length with her, my roommates, and my family. I would have to self-isolate at home when I returned, but that seemed likely no matter what happened.

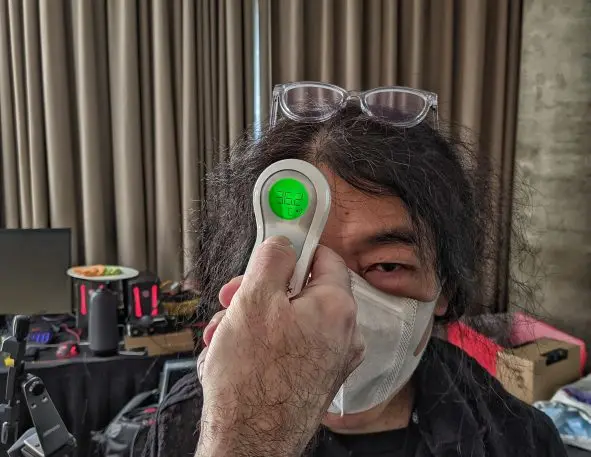

With frequent handwashing and easy-to-maintain social distancing while traveling and at the conference, and masks and gloves available if I started to show even the slightest symptom, it seemed like I could navigate the risk of infection relatively easily. (Full disclosure: CanSecWest’s organizers covered part of my travel expenses.)

When I showed up for the first day of the conference, on March 18, there were none of the loud greetings between old friends that are as much a part of the fabric of hacker conferences as trading pentesting stories. Except for a few guests and the desk clerks, I could’ve walked onto a horror movie set. Empty hallways and escalators echoed with every footstep, and it smelled empty, the ventilation system circulating unused air.

I asked myself for the umpteenth time that morning, ‘What the hell am I doing here?’

When Ruiu and I sat down to chat on the second day of the conference, he remained optimistic that technology had saved the conference. Though attendance for the training classes was low, one class that could have been a disaster in person turned into a virtual success. The instructor was stuck in Israel, the demo devices for students to hack were already in Vancouver, and a dozen students were dispersed around the globe. “We’re so pleased with the feedback, we’re looking at doing more of these courses,” he told me. “Our bottom line is that we’ve been emboldened by the results.”

With the global economy teetering on the brink of recession, Ruiu said that the CanSecWest attendees who participated in the conference virtually may have shown him a path on how to stay afloat—or even thrive—in the coming downturn. He even arranged for DJs to play sets on the conference Zoom live stream to keep the audience engaged in between talks.

So why did CanSecWest 2020 even have an in-person component? Ruiu says that he wasn’t worried about the attendees who showed up. “People at our conferences are in charge of things that go boom,” he says of his clientele of security professionals. “They’re responsible folks. I made the call that they can be trusted to self-isolate if they show symptoms. And we have masks, [hand] sanitizers, and room to have social distance.” (Never mind a minimum of six feet social distancing—I easily had 16 feet or more between me and other people at the conference.)

Dragos Ruiu, founder, CanSecWestPeople at our conferences are in charge of things that go boom. They’re responsible folks.”

Johnson sat down at a small table in the conference area with me, wearing a disposable medical face mask, and said he came because he felt he was at relatively low risk of infection. “I’m in my late 30s, in good health. In terms of spreading it, I’m happy to take precautions,” he said, such as using hand sanitizer and maintaining social distancing. “My wife is concerned about me coming here. But I work from home, I’m fairly isolated anyway.”

He left the conference shortly after we spoke.

The lessons of going virtual

CanSecWest may just barely have taken place as an in-person event. However, it made up for it in online followers. Ruiu gave each CanSecWest registrant and speaker four access codes to the live stream. At its busiest, Ruiu said that 181 people were watching and commenting on the conference’s Zoom live stream—around 45 percent of the conference’s usual attendance.

“I’ve learned things, watching these presentations.” he told me. “Being paralyzed and calling things off may not be the answer. The fear and the panic has stunned some folks, like deer dazed in the headlights. Let’s try tackling some challenges.”

But when it comes to tackling challenges, today’s governments have been woefully unable to face the task. President Donald Trump disbanded the pandemic preparedness task force, then ignored the coronavirus outbreak until states started shutting down. He wasn’t the only one; most officials and the media followed Trump’s lead until the disease had battered down their front doors and moved in. Vigorous and regular handwashing, appropriate use of face masks, and sheltering in place to enforce social distancing appear to be the only measures that work at this time to combat the coronavirus.

As vital as it is for as many people as possible to stay at home, it’s equally important that journalists be counted among essential workers who investigate and report on how the world is coping with the coronavirus and COVID-19. I would have preferred to stay home and not take the risk. But ultimately, I’m glad I made the trek to Vancouver. In a bleak time, there are signs of hope as communities such as Ruiu’s figure out how to move forward.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.