David Jones had several hours to kill at the Kuala Lumpur airport en route back to Melbourne, so he camped out in a lounge chair and watched as installers set up heat-detecting cameras nearby.

His sighting was apropos. Jones, who is a planning and landscape architecture professor at Australia’s Deakin University, had recently cowritten an academic paper arguing that by sharing data, cities could work together to understand and manage response to outbreaks such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

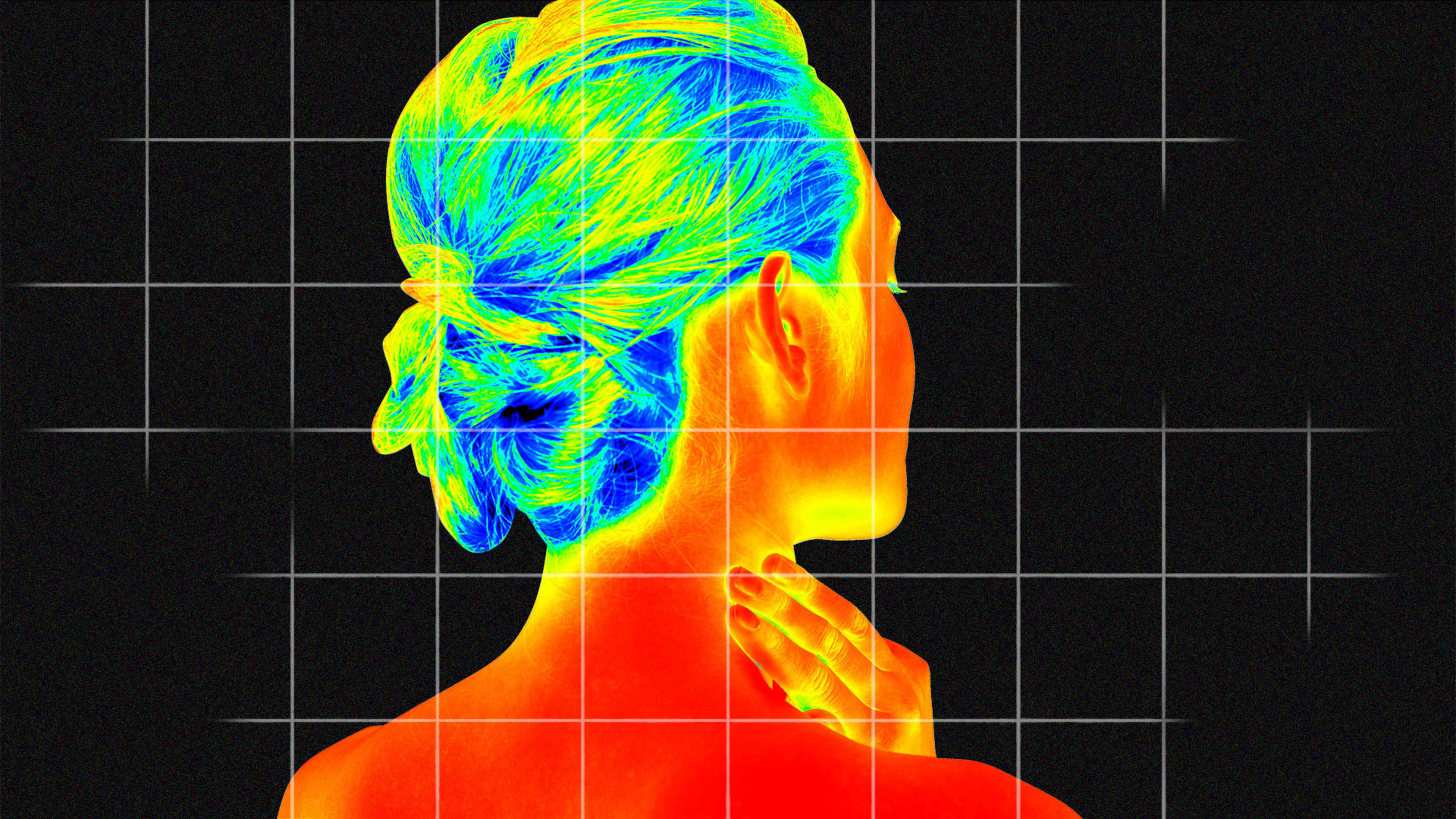

Now, Jones was watching thermal screening cameras being installed for that very purpose—to spot people who could be experiencing a high body temperature, a symptom of the coronavirus. Jones says he hopes that city managers and government policy makers will work to monitor and control the impact of the pandemic by using data from thermal cameras, patient-tracking wearable devices, and existing mobile location data.

In many ways, that effort is already underway. Cities overseas are using thermal cameras to detect symptoms of infection. Some places, including China and Hong Kong, have employed drones to monitor excessive social interaction or connected wristbands to ensure patient compliance. Even here in the U.S., the White House has considered the use of mobile location data analytics for tracing contact among residents.

But while using this data effectively can save lives, the global mobilization to save people from the scourge of COVID-19 also reveals the urgent need for governments to set policy for sometimes-untested surveillance tech and data use. If data is employed to track down new cases of COVID-19 and to urge close contacts to quarantine, what happens to that data once the pandemic is over?

In many of these cases, there is a clear potential for law enforcement, health insurance firms, and local governments to misuse or abuse data, a problem that could haunt us long after the pandemic subsides. Data first gathered during a health emergency could wind its way through our country’s patchwork of private health insurance firms and be used to determine insurance rates or even to deny coverage, says Aaron Shapiro, a research fellow at NYU’s Information Law Institute and author of the forthcoming book, Design, Control, Predict: Logistical Governance in the Smart City.

Because the technologies cities use are almost always made by corporations, Shapiro says that government policies for emerging tech could be driven by those companies’ market functions and profit goals—instead of being guided by the needs of a city and its communities.

“The complexity of surveillance in this age is when something like public health surveillance is implicated in commercial surveillance,” Shapiro says. “There’s no way to disentangle them.”

Spotting symptoms with surveillance

Pandemic surveillance tech—such as thermal cameras in public transit hubs or drones policing social interaction—has already proliferated in parts of Europe and Asia.

Tens of thousands of handheld or mounted thermal cameras made by the company FLIR Systems have been installed in transit hubs, hospitals, stadiums, and factories throughout Asia, Europe, and the Middle East—from train stations in Italy to the airport in Dubai. Though many of the cameras have been used in response to the SARS epidemic or the Ebola outbreak, the firm has sold more cameras recently in those places to spot people with high body temperatures.

Aaron Shapiro, NYUWhen something like public health surveillance is implicated in commercial surveillance . . . There’s no way to disentangle them.”

So far, there do not appear to be any states or municipalities in the U.S. employing this type of tech. And unlike in authoritarian countries such as China, there is no coordination here among cities networked through digital and data infrastructure, making widespread surveillance less likely.

While some U.S. cities have used FLIR system’s cameras to detect body heat of intruders at ports, none here have used them yet to take temperature readings in response to the pandemic. Now though, FLIR is talking to municipalities and corporations in the U.S. that could use its thermal cameras for detecting potential COVID-19 cases. “We’re in a lot of conversations right now in North America,” says Frank Pennisi, president of the industrial business unit at FLIR Systems.

Unlike some thermal cameras that detect body temperatures as groups of people walk by, FLIR Systems’ cameras measure heat when aimed at an individual’s eye area. Pennisi stresses the cameras cannot detect an infection or a virus—just a body temperature above a normal baseline.

As for data capture, the cameras do not grab a recognizable photographic image of the person whose temperature is measured. And they are designed to keep temperature readings of just 10 people before purging that information. However, the cameras can be outfitted with a memory card for more temperature data storage, Pennisi says.

This is where municipal government policy might come in. Tech ethics and privacy advocates suggest city officials should think about whether or not to store data captured by emergency technologies, and decide who has access to it and for what purposes before disaster strikes.

Adam Schwartz, EFFAt the front end, ideally [cities] have a privacy officer who’s raising these issues ahead of time.”

“At the front end, ideally [cities] have a privacy officer who’s raising these issues ahead of time,” says Adam Schwartz, senior staff attorney at Electronic Frontier Foundation. “It needs to not be the department of transportation director and a corporate salesperson who do this.”

Cities might also use a network of smart city sensors to aid in the fight against the pandemic. Recent research has evaluated the use of “ambient” city tech to monitor public health on a community level—things such as mobile sensors installed in public areas, and data gathered from the transportation grid or vehicle networks. But Dr. Shelly Fritz, who participated in that research, says she is not aware of cities in the U.S. employing this sort of emerging urban tech in response to the pandemic.

Fritz, who is an assistant professor of nursing at Washington State University, is knee-deep in COVID-19 response efforts in her own community in Lewis County, Washington. Even if municipalities were to gather data from sensors, apps, or other devices, she questions whether any have staff with the appropriate technical skills to put it to use.

“I don’t think our municipalities are set up to use that data,” Fritz says.

Using data to trace disease transmission

Though thermal cameras and smart city data isn’t yet being used in the U.S., other kinds of data—particularly mobile location data—is already being tapped to stop the disease’s spread. Even before a COVID-19 infection becomes known to a patient, epidemiologists can use sophisticated data analysis methods to deduce who has been in the disease path. For instance, investigators can trace the route of transmission using mobile location data combined with other information, such as credit card transactions. Analysis can determine where a patient made contact with others who visited the same locations or made purchases at the same places.

This technique, called contact tracing, has been used by COVID-19 investigators in China and South Korea to mitigate the spread of this coronavirus as well as other illnesses such as Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. In addition, technologists in Britain are developing a voluntary National Health System mobile app that would use location data and alert people who may have come in contact with those who test positive. And Israel last week approved emergency rules allowing security agencies to use mobile location data to track people who may have come in contact with those infected with COVID-19.

Senator Ed MarkeyI urge you to balance privacy with any data-driven solutions to the current public health crisis.”

The giants of tech are involved in using location data analysis at the federal level here in the U.S., too. The White House has been working with firms including Amazon, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft to devise ways to use mobile location data to understand the path of the pandemic.

Reports of those efforts have sparked concern from privacy and civil liberties advocates. Last week, Senator Edward Markey (D-MA) sent a letter to Michael Kratsios, chief technology officer of the U.S., asking for details of the project.

“I urge you to balance privacy with any data-driven solutions to the current public health crisis,” stated Markey.

Currently, there are no federal U.S. laws regulating the use of this data collection technique, and it is unclear how far along the government’s efforts are to use contact tracing methods to understand the path of the virus.

The civil liberties conundrum

Contact tracing using mobile location data is just one of the ways that epidemiologists, biotech researchers, data scientists, and other health professionals are calling for governments to use. Technology like this could mitigate the impact of the pandemic “and save between thousands and millions of lives.”

A handful of these experts put together a list of ways technology could be useful on a website called Stop-Covid.Tech. One example? “Apple, Google, and other mobile operating system vendors should work to provide an opt-in, privacy preserving OS feature to support contact tracing. . . . In the longer term, such infrastructure could allow future disease epidemics to be more reliably contained, and make large-scale contact tracing of the sort that has worked in China and Korea feasible everywhere,” the experts wrote.

However, the civil liberties and privacy implications of using mobile location data for contract tracing are unclear. If mobile location data were combined with identifiable information or data from fitness trackers or social media networks, Schwartz says, “this could get Orwellian very fast.”

Some medical professionals in the tech sphere are more comfortable with swapping away some privacy to save lives. “I think China should be credited with the lives they ended up saving,” says Este Geraghty, chief medical officer and health solutions director at Esri, a mobile location data and mapping firm. Esri has distributed data visualization dashboard templates used by health agencies both overseas and in the U.S. The company’s visualizations for Cobb County, Georgia, and San Benito, California, show COVID-19 testing locations and inventory of hospital beds as well as surface non-identifiable information on how cases are spreading.

Este Geraghty, EsriI probably wouldn’t mind if somebody downloaded my cellphone data. I would be grateful.”

“There’s no question in my mind the times we’re living in now are completely unprecedented,” Geraghty says, acknowledging that governments could use location data access for unapproved purposes that have nothing to do with preventing disease spread.

However, she says that if she contracted COVID-19 and her previous contact with other people could be traced using location data from her mobile phone, “I probably wouldn’t mind if somebody downloaded my cellphone data. I would be grateful.”

Wearables meet the pandemic

When someone has tested positive for COVID-19 or is forced to remain in isolation after traveling, some governments are using tools such as wearables to keep an eye on them. In Hong Kong, for instance, all arriving passengers now are outfitted with an electronic wristband linked to a mobile app.

These are the tools of “real-time personal health monitoring” and “ubiquitous healthcare”—buzzwords that are nothing new in the world of health and medical tech. As a result of the pandemic, it is likely more governments and corporations are considering using wearable gadgets to monitor vital signs of patients and employees.

These might include the digital health bracelets made by the startup Spry Health, which now has a dedicated COVID-19 page on its website. The firm’s technology gathers data on a patient’s blood oxygen level, respiration rate, and heart rate throughout the day, transmitting it to a system monitored by nurses. It uses machine learning to identify and contextualize patient baselines and detect problems.

Aaron Shapiro, NYUThere has to be some sort of a guarantee that companies won’t get that data.”

Pierre-Jean Cobut, the company’s CEO and cofounder, says municipal health departments in the U.S. have discussed using the patient-tracking technology in response to the pandemic.

“The underlying message from all these organizations is that they need a quick way to prioritize care to those that need immediate attention, while still monitoring their at-risk population to identify future escalations,” Cobut says of the firm’s potential pandemic-related customers.

NYU’s Shapiro says he worries about how data from wearables used to oversee COVID-19 patients could be used against them in the future. An insurance firm could find out a patient left home when she was supposed to comply with home quarantine, for instance. “There has to be some sort of a guarantee that companies won’t get that data,” he says.

For now, most city-level responses to COVID-19 in this country seem to be employing traditional approaches. However, if U.S. municipal governments begin using emerging tech and advanced data gathering and analysis techniques in response to the pandemic, they should make sure there’s an expiration date for extraordinary tech and data use, Schwartz says.

“Whatever extra measures we use to deal with coronavirus, they have to expire when coronavirus ends.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.