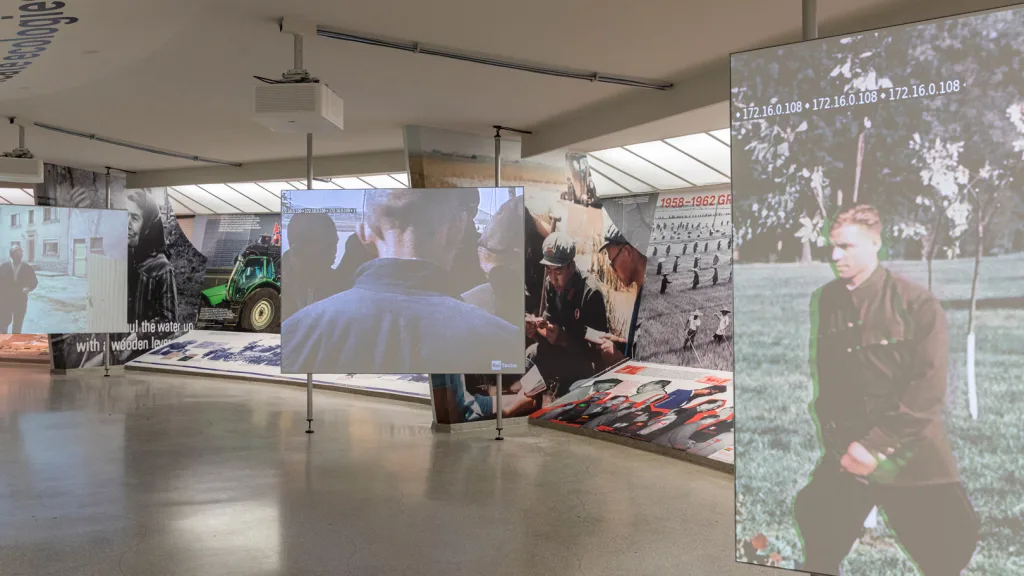

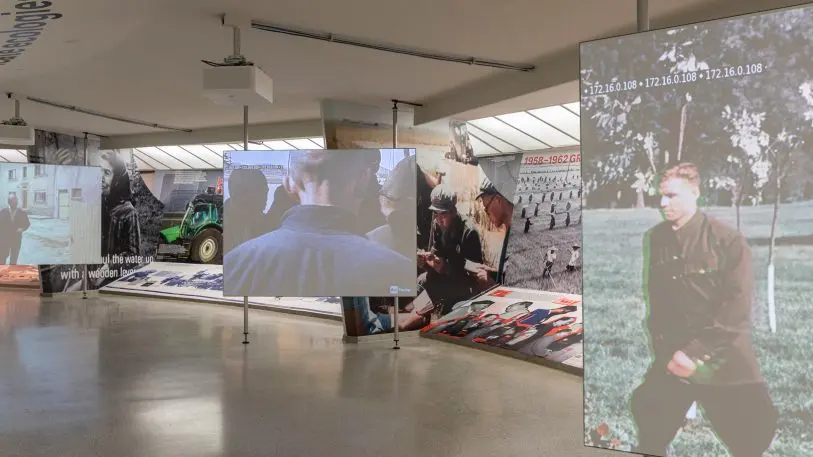

Before coronavirus shuttered museums across the country, the Guggenheim was home to one of the most unusual architecture exhibits of the year. Countryside, the Future explores how the world’s non-urban territories might one day be designed, and it is a collaboration between legendary architect Rem Koolhaas and Samir Bantal, the director of AMO—Koolhaas’s practice’s research studio.

As the urban environment becomes more saturated (half of the world’s population currently calls cities home), designers are starting to consider what rural living might look like. Koolhaas’s show highlights the advancements that several countries have already made in developing the countryside. Before the museum closed, Co.Design spoke with Koolhaas and Bantal about the exhibit, why rural communities need investment, and why Trump is on the wrong side of history when it comes to climate change.

Co.Design: How does this area of inquiry fit into your broader career and intellectual interests over the years? Why did you feel the need to investigate this now?

Rem Koolhaas: I’m a former journalist, and the most driving force of journalism, as you probably know very well, is curiosity. I’ve got a well-developed stance on either areas that are being ignored or questions that will become important in a couple of years, so I’ve always been able to have a kind of intuition about issues that are becoming relevant.

CD: Obviously not every countryside is the same. How realistic is a template?

RK: We don’t see it as a show about architecture, or a what kind of architecture you could build where. We simply see it as a way of identifying a number of conditions globally.

CD: What are the business implications of ignoring the countryside like we have for the past however many years, and what are the possible advantages of investing in it, especially now?

Samir Bantal: One element from the show that we try to expose is that in the early part of the 20th century planning, and especially planning on a larger scale, was part of the way to deal with urgent issues like climate change and food production. We’ve kind of lost the ability to be involved in that form of large-scale planning. And most of the elements that cities need, to accommodate our lifestyle in the city, are actually happening in the countryside. Ignoring the countryside means that we are ignoring the opportunity to be involved in that part that sustains urban life.

RK: Banks, hedge funds, and other components of the financial world are now also becoming convinced that they need to go green. And maybe profit should not dominate in all cases. The countryside offers a huge amount of opportunities to develop new economies and new kinds of sustainable models of growth—much more than the city. I think in the city you can make really marginal improvements, but in the countryside there’s a vast demand for innovation.

CD: Do you think that the right architecture can encourage people to move out of cities?

RK: In an office [there are usually] people working behind computers on single tables. When these people want to communicate, they very often send emails to people that are sitting less than four feet away from them. You could argue that basically a lot of work digital communications are used for in cities is to create a kind of bubble. And to, in a way, erode the directness of human contact for human exchange—and therefore, also really erode the whole notion of interaction and physical interaction, which used to be and which I still believe is the point of cities.

If you now look at China, you see how the internet is used to actually create completely new connections between cities and the countryside. And to enable people who are remote from cities to have a life that is connected to cities, that responds to cities, but is still viable and credible on the countryside.

CD: Environmentalism is a big theme in the show. Do you think that a sustainable future for architecture is one where things are actively built less or simply built differently?

RK: Both, because there is an enormous amount of buildings that are not strictly necessary that are being built. Around the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s, [architecture] was very aware of the need to build differently and very aware of ecology. R. Buckminster Fuller’s book Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth was an analysis of the entire planet and how sustainability was a totally different approach . . . [It] was very sophisticated in terms of suggesting how architecture should be built and how it should avoid any abuse of the planet. In other words, architects were an early professional group that was totally aware [of environmental considerations]. . . . But I think the story of the ’80s, ’90s, and 21st century is that we have found very few clients willing to pay for this awareness or willing to pay for the consequences. And the interesting thing today is that the pressure to do so is vastly increased. This is a significant moment for architects because it could be the first moment that clients can be convinced to allow architects to build much more intelligent architecture.

SB: To that point, architects and the economic models that we use have always designed for growth. And so cities were always planned to accommodate growth. However, there are many examples especially in the countryside where there is no growth but only a kind of shrinking. We are missing the kind of approach or tools or even design thinking to design for a shrinking society or a shrinking area, so in that sense, there’s definitely still a realm for architects to explore.

CD: What are some of the challenges as intellectuals, architects, designers, and thinkers to work against the denials of things that the environment is showing us is true? Especially when we have a president who doesn’t even believe in climate change.

RK: In the last few decades, maybe since the fall of the [Berlin Wall], there has been a kind of unraveling of many different kinds of international connections and a global knowledge base. It’s much larger than considering Trump and whether he believes in climate change or not; it’s really that unraveling which is disturbing, and is what some of the more courageous bureaucrats in the world, that are in charge of somehow averting this kind of situation, are fighting. The evidence of climate change is now so blatant that it’s become almost irrelevant whether Trump believes in it or not because the whole of America believes in it.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.